William Thornton Watson was born on 10 November 1887 at Nelson, New Zealand, son of Tasmanian-born Robert Watson, blacksmith, and his Victorian wife Annie, née Harford.

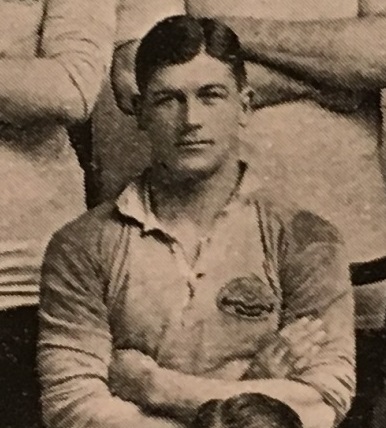

At age 24, he relocated to Sydney and joined the inner-city Newtown Rugby Union Club, playing at prop. In 1912, he made his representative debut for New South Wales and that same year was selected for the 1912 Australia rugby union tour of Canada and the USA (Wallaby number 123). The American newspapers, aware of Australia’s Olympic gold medal for rugby, dubbed the visitors ‘the world champions of rugby’ but the tour was a disappointment with the squad billeted out in college fraternity houses where the hospitality played havoc with team discipline. As a result, the team lost against two California University sides and three Canadian provincial sides but rose to the occasion for the sole Test of the tour – the November 1912 clash against the United States at Berkeley, won 12-8. Watson played in the sole Test match of the tour as well as ten other tour matches of the total possible sixteen.

Watson made appearances for New South Wales in 1913 against the visiting New Zealand Maori. He toured New Zealand with the 1913 Wallabies captained by Larry Dwyer, appearing in a total of eight of the nine matches played. This included all three Tests where he packed the scrum in a consistent front-row combination with Harold George and David Williams.

When the All Blacks toured to Sydney in 1914, Watson was picked to play against them for New South Wales, as a Wallaby in the first Test at the Sydney Cricket Ground, and in a Metropolitan Sydney side in a mid-week game. An injury prevented his selection in further representative appearances against them. The outbreak of the First World War on 4 August 1914 forced the All Black tour to be cut short.

Three days after war was declared, Watson enlisted in the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF). The AN&MEF’s objectives being the capture of the radio stations in German New Guinea. Watson saw action seizing the German wireless stations in New Britain and New Ireland.

With the AN&MEF’s objectives quickly achieved the organisation was disbanded and Watson was discharged in January 1915. Watson then enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) as a gunner and reinforcement for the 1st Divisional Artillery. He embarked from Sydney on 26 June 1915, landed at Gallipoli on 14 August 1915, and two days later joined the 1st Field Artillery Brigade. He was involved in the defence of ANZAC Cove and the battle of Sari Bair.

After service at Gallipoli in March 1916 he proceeded with his unit to France where his temporary promotion to sergeant was confirmed on 22 April 1916. During operations on the Somme from 26 October 1916 to 15 January 1917, Watson was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions. The citation reads: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He displayed great gallantry and coolness in going to the assistance of wounded men, under heavy fire. He has set a splendid example throughout.”

He was then posted to England for officer training and was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant on 7 September 1917. He then joined the 2nd Field Artillery Brigade in Belgium where he was wounded in action on 17 November 1917, receiving a severe gunshot wound to his abdomen.

Promoted to Lieutenant on 7 December 1917, he returned to duty in April 1918 and was at Foucaucourt on 27 August 1918, acting as forward observation officer with the infantry. When the advance was impeded by enemy machine-gun fire, Watson worked his way forward and directed three batteries barraging the German machine-gun posts. For his conduct Watson was awarded the Military Cross. The citation reads: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty at Foucaucourt on 27 August 1918, when he accompanied the attacking infantry as Forward Observation Officer. The enemy offered strong resistance, frequently holding up the advance with machine-gun fire. In one case he worked his way forward several hundred yards in front of our outposts, directing the fire of three batteries, which gave great assistance to the infantry by barraging machine guns nests and strong posts. He showed fine courage and initiative throughout.”

In one of the final actions of the war, Watson would be awarded a Bar to his Military Cross for his actions at Nauroy in France near the St. Quentin Canal and the Hindenburg Line. The citation reads: “For conspicuous gallantry at Nauroy near Bellicourt, on the night of 2-3 October 1918. His battery was the centre of an enemy bombardment which continued for over four hours. Though badly gassed himself, he tried to save the life of a wounded officer. He showed great energy and devotion to duty and stayed with his battery until the next day, when it was withdrawn from the line.”

At war’s end and during the long process of returning 250,000 Australian AIF troops from Europe, Watson was selected as captain of the AIF First XV. The team represented the Australian Forces in the King’s Cup Rugby Competition among the nations represented in the allied armies with teams representing the British, Canadian, New Zealand and South African armies as well as the Royal Air Force. When playing with the AIF team as a front-row forward, Watson must have suffered excruciating pain as he was covered in festering sores, the after-effects of mustard gas. Major Walter ‘Wally’ Matthews, the team manager, frequently had to open these festering sores with a sterilised penknife before Watson took to the field. On the AIF Team’s Australia Tour Watson played in five of the eight games, all as captain.

At war’s end and during the long process of returning 250,000 Australian AIF troops from Europe, Watson was selected as captain of the AIF First XV. The team represented the Australian Forces in the King’s Cup Rugby Competition among the nations represented in the allied armies with teams representing the British, Canadian, New Zealand and South African armies as well as the Royal Air Force. When playing with the AIF team as a front-row forward, Watson must have suffered excruciating pain as he was covered in festering sores, the after-effects of mustard gas. Major Walter ‘Wally’ Matthews, the team manager, frequently had to open these festering sores with a sterilised penknife before Watson took to the field. On the AIF Team’s Australia Tour Watson played in five of the eight games, all as captain.

After returning to civilian life Watson took up first grade rugby again and at age 32 joined the new venture Glebe-Balmain club – the two prior clubs had merged as a result of the player losses each had suffered in the War. Watson was the captain of Glebe-Balmain from 1919 to 1924. In 1920 he was selected as captain of the New South Wales state team and led them in three matches against a touring All Blacks side. With no Queensland Rugby Union administration or competition in place from 1919 to 1929, the New South Wales Waratahs were the top Australian representative rugby union side of the period. A number of their fixtures of the 1920s played against full international opposition were decreed by the Australian Rugby Union in 1986 as official Test matches. Though he was not aware of it at the time, Watson’s three appearances as captain of New South Wales were Test match captaincy fixtures. All told, Watson played 46 matches for Newtown, 13 for Glebe-Balmain and 22 matches for New South Wales. He played 24 matches for Australia including the three NSW Tests of 1920 plus five other pre-war Tests.

After the war Watson lived in Papua New Guinea working in a range of industries including copra production, cattle ranching and prospecting for gold in the then practically unknown Owen Stanley Ranges. In September 1929 he married American-born Cora May Callear in Sydney. They relocated to Columbiana, Ohio, in 1935.

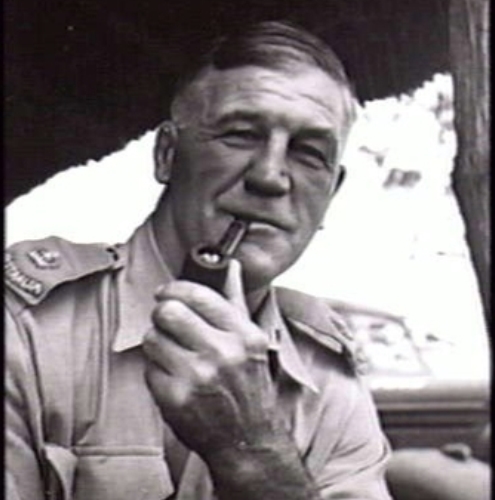

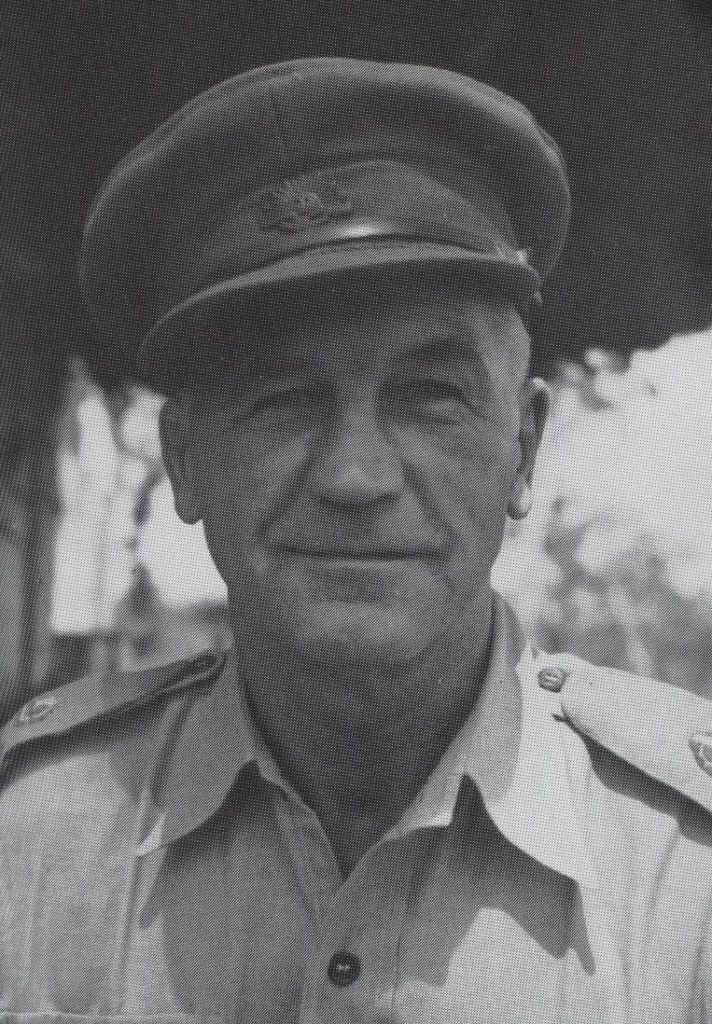

At the commencement of Second World War, Watson returned to Australia and served in the 2nd Australian Garrison Battalion from March 1940. In June 1940, his pre-war New Guinea experience (and his ability to speak local New Guinea dialect) was put to use when he was posted to the Papuan Infantry Battalion (PIB), a force of native soldiers, and Australian officers and NCOs. Watson took command of the unit in 1942.

With Japan’s invasion of New Guinea on 21 July 1942 and the commencement of the Kokoda Track campaign, the PIB were the first Australian Army unit to make contact with the Japanese. The battalion, an element of Maroubra Force, was dispersed between Awala and the north coast when the Japanese landed at Buna and Gona on 22 July 1942. Outnumbered, the PIB fell back before the advancing Japanese; its remnants linked up with leading troops of the 39th Battalion, fought rear-guard actions at Gorari and Oivi, and rejoined Lieutenant Colonel W. T. Owen, the Maroubra Force commander at Deniki.

Having abandoned the position prematurely, Owen reoccupied Kokoda on 28 July 1942, his force having been reduced to about 80 men. The Japanese attacked that evening and when Owen was killed, Watson took command. Watson led a fighting retreat back towards the village of Deniki, a mile or so back along the Kokoda Track towards Isurava. Watson remained in command of Maroubra Force until 4 August 1942 when he was relieved by the arrival of a more senior commander.

For his bravery and leadership during the withdrawal, Watson was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. He was promoted to Major on 1 September 1942 and remained as the Commanding Officer of the PIB. The PIB subsequently carried out useful work, patrolling the flanks of the Australian-American forces as they pushed northward against the Japanese.

Watson relinquished his command on 30 March 1944 and on 7 July 1944 was transferred to the reserve list. After the war, he returned to the United States and was appointed as Australian Vice-Consul in New York until 1952. Survived by his wife, daughter and son, Watson died on 9 September 1961 in the Veterans Administration Hospital, Brooklyn, New York.

Contact Marcus Fielding about this article.