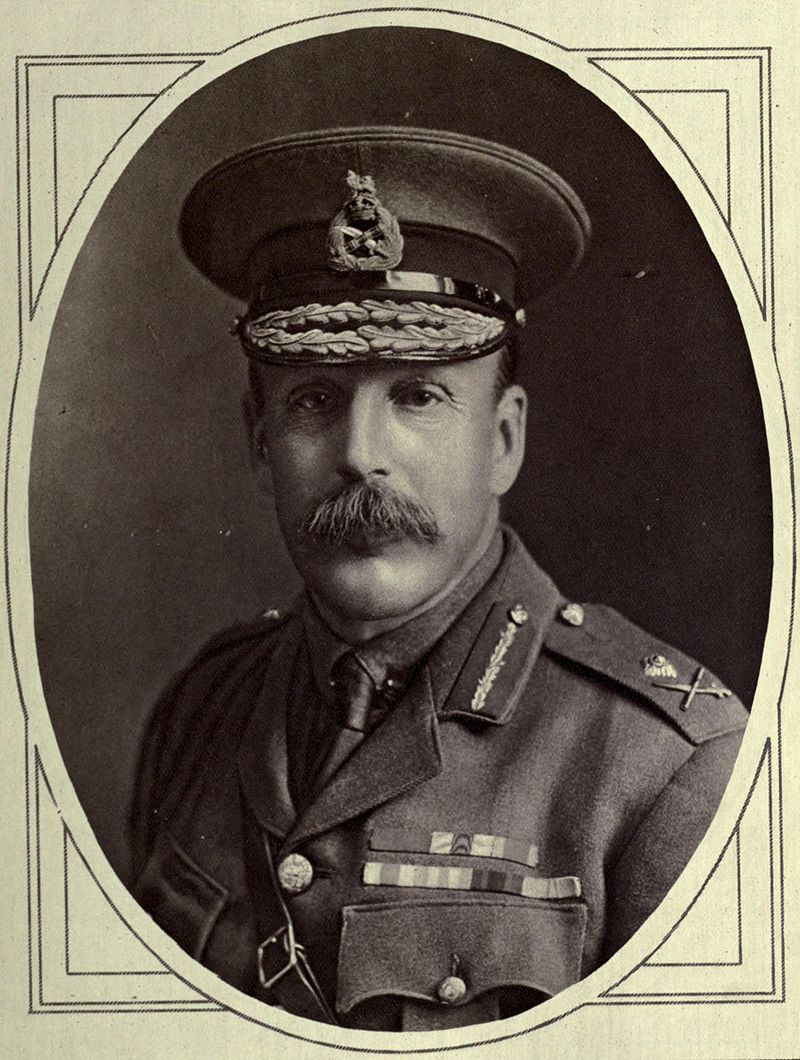

Lieutenant-General Sir Stanley ‘Joe’ Maude was one of the First World War’s most successful fighting Generals. He had a lifetime career in the British Army, with service in South Africa from December 1899 to February1901,France in 1914 and the Dardanelles in 1915.

Maude was appointed to command of the shattered 13th Division at Suvla in mid-1915.This division had sustained terrible losses during the Suvla campaign and Maude’s skills were judged as being able to reform the Division and lift morale.

The 13th Division was returned to Egypt after the evacuation of the British forces from Helles in January 1916. The Division was then allocated to the Mesopotamian campaign and over the next two months was relocated to Basraat the mouth of the Tigris River.

The Ottomans had besieged a garrison under General Townsend at Kut since 7 December 1915.The operation to relieve Kut began in March 1916 after Maude had arrived from Egypt with the 13thDivision.This relief operation was unsuccessfuland General Townsend subsequently surrendered Kut on 18 April 1916.

On 10 July 1916 Maude, at this time only a junior divisional commander, was suddenly promoted to head up the Tigris Corps with orders to recapture Kut. Maude’s new strategy and tactical skills as a Corps commander concluded with great success with both the retaking of Kut and the captureof Baghdad on 11 March 1917.

Maude’s attention to detail and his organisational skills with supply and medical facilities were outstanding and the capture of Baghdad from the Ottoman’s was seen as a great occasion to celebrate during the dark days of 1917.He was a great hero in Britain and received congratulations and accolades from the King, Grand Duke Nicholas of Russia, many Commonwealth Dominions, as well as the Viceroy of India, the Secretary of State for the War and many of his Army colleagues and commanders of British Armies in other theatres of war. He was the great hero of the day and highly respected by every man under his command.

This historical claim to fame, the first capture of Baghdad by a Christian was not Maude’s first significant historical achievement. His service on the Gallipoli Peninsula during the Suvla campaign and his subsequent rear guard action at Helles when he was reported by several very reliable sources, including Sir Ian Hamilton and General Sir C.E. Callwell, to be the last man to step off the Gallipoli Peninsula on the early morning of the 9th January 1916 is also regarded as a significant historical claim to fame.

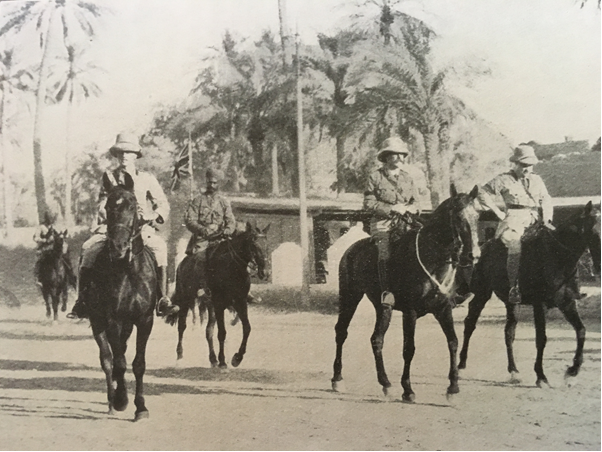

The Tigris Corps settled in Baghdad in late March 1917after months of difficult fighting, to regroup, re-equip and refresh. The heat in Baghdad during the summer period was intense – over 40 degrees C during the day with little relief at night – and most fighting action was suspended. Maude used this time to ensure his men were well looked after and to strengthen his supply line. He spent most of his precisely planned days visiting units, hospitals, and ensuring that Baghdad was back under law and order after the many years of Turkish rule.

Maude was at the peak of his Army career in late 1917 and was planning in conjunction with General Allenby – who was pushing through to Damascus through Palestine – for the next stage in the removal of Ottoman control in the Middle East with a winter offensive. But then Maude died suddenly on 18 November 1917after three days of illness.

The initial reaction was “how could this possibly happen?” Throughout his life Maude had always been active and fit, he rode for exercise every day and any sickness he sufferedwas quickly overcome. The only physical injury he ever suffered was a damaged shoulder from a fall from his horse in the South African War. As the news of his death spread through the ranks, a rumour started that he must have been poisoned.

The next section of this paper will prove conclusively that Maude was not poisoned. The research for this conclusion has taken many years and includes discovery of the original 1918 reports, together with eye witness accounts of the critical three days prior to his death.

Maude had settled well into Baghdad, living in a most comfortable house that had been previously occupied by the German Army officer in command of the enemy forces Baron von der Goltz. With his staff and two aides he was enjoying doing all the many things that required his involvement during this non active period. It was a good time and all reports indicate he was very relaxed and looking forward to the next operation towards Mosul. Even so, he never spared himself and worked incessantly – except for his evening horse rides which he always looked forward to.

He was a charming host and was determined to make all visitors welcome and their stay as pleasant as possible. In late October 1917 Maude received a request from an old friend Lord Willingdon, the Governor of Bombay, asking if Maude would permit a lady, Mrs Egan, who represented an important syndicate of American newspapers, to visit Mesopotamia and his Headquarters in Baghdad. The request was approved and Mrs Egan duly arrived on 11 November 1917 to stay with the Tigris Corps Commander.

Maude was a charming host and ensured that Mrs Egan should see all that was worth seeing in and around Baghdad. In her book ‘The War in the Cradle of the World’ she provides a very sympathetic and animated description of Maude’s mode of life during this time.

He arranged on 14 November 1917to take her to a theatrical show at a Jewish School. In her book she gives a detailed account of the elaborate precautions for guarding the route taken. During the interval coffee was served, Maude took milk, she did not.

Two days later on 16 November 1917 Maude went to his office as usual. Later in the morning he felt and looked unwell. At 7.45am he sent for the staff Surgeon Dr.Maloney, who prescribed ‘for him to be quite with milk diet’. Maude returned home but insisted on dictating correspondence during the afternoon.

At 6.00pm Maloney brought Colonel Wilcox, the Consulting Physician of the Force, with him to check on Maude’s condition. No obvious serious symptoms were present but Wilcox insisted that Maude cancel all his commitments for the evening.

Maloney called on Maude later in the evening and noted with concern that a change for the worse had taken place. Wilcox was again summoned. Maude’s illness was then diagnosed as a virulent strain of Cholera. The milk from the Jewish School was assessed to have been contaminated with the Cholera bacteria.Maude had refused to be inoculated believing that a man of his age was immune.

Colonel Wilcox gave the following eye witness account of the course of the illness.

‘At about 7.45pm on Friday 16 November 1917 an acute attack of Cholera commenced with great suddenness and, in a few minutes, a state of extreme collapse occurred. Without delay immediate treatment was adopted and everything possible was done to combat the acute symptoms. Lt Maloney and myself as consulting physicians remained with General Maude throughout his illness. Miss Walker, the Matron of No. 31 British Stationary Hospital, and four specially selected nurses carried out with greatest care and devotion their nursing duties.’

Maude retained his mental ability in spite of his great weakness until just before his death. A few hours prior to his death he received a telegram from Lady Maude and was able to dictate an encouraging reply.

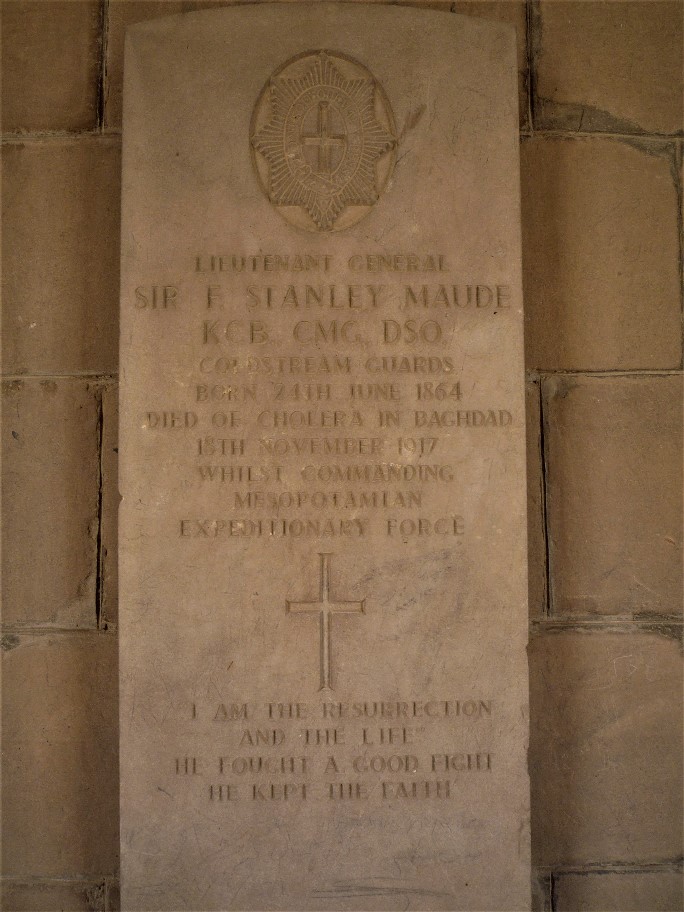

At 4.30pm on 18 November 1917 Maude fell unconscious and passed away peacefully at 6.25pm. The cause of death was “cardiac failure consequent on the toxaemia of a very severe cholera injection.”

General Stanley Maude was buried on the afternoon of 19 November 1917 in the desert cemetery beyond the North Gate of Baghdad. Every officer and man who could be present was there to pay a last tribute of respect and affection to their departed commander. A simple cross marked the spot where Maude was buried.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission subsequently erected a stone monument to Lieutenant-General Maude which still stands today in the Baghdad North Gate Cemetery.

His memory was honoured in 2009 by Australian soldiers in Baghdad, during the Australian Anzac Day commemorations held at the North Gate Cemetery, where 41 Australian servicemen also rest in peace.

Contact Peter Fielding about this article.