At Federation, the former colony that had most to contribute to the Commonwealth Naval Forces which came into being on 1 March 1901 was Victoria.

Sydney had long played host to the intermittent British efforts to provide its colonial possessions in Australia with naval protection, and it has to be said – at the risk of upsetting those that live south of the Murray, that it would be difficult to find a more splendid piece of real estate upon which to build Admiralty House than the site it occupies in Kirribilli overlooking Sydney Harbour.

The New South Welshmen thus could rely on there being a Royal Navy squadron of sorts to defend it against foreign aggression in or not far away from Sydney. Victorians, on the other hand, rarely saw the British ships and had suffered the indignity of having a real foreign warship – not those imagined bogeymen much beloved by the Sydney press – making free of the facilities of Port Phillip in the shape of CSS Shenandoah. Over time, therefore, Victorian governments had equipped themselves with a range of warship in self-protection, as they were permitted to do.

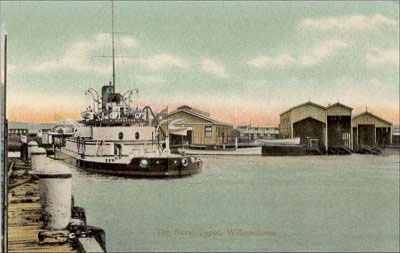

Victorian naval units had been involved in the Maori Wars, the Sudan War and most recently in suppression of the Boxer Rebellion in China. Its modern and effective naval forces were restricted to two torpedo boats, but the bulk of HMVS Cerberus was reassuring and her guns larger than those of most ships that might brave the forts and force an entry into Port Phillip. But the Victorians also had several other aces up their sleeves, including but not limited to an effective naval brigade that had fought in China, a functioning Ministry of Defence, and Williamstown Naval Base, which had operated since 1885.

The windfall of being appointed the capital of the new Federation, while inter-state bickering resolved the issue of where the national capital should be located, only served to underline these advantages. While the federal Parliament relocated to Canberra in 1927, it was 1964 before the headquarters of the Royal Australian Navy was finally prised out of Melbourne, so Victoria played host to the RAN for fully half of its existence.

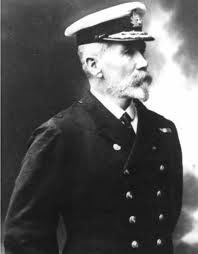

The early years after Federation saw little in the way of naval development in Australia. The revolving door that saw ten Ministers for Defence in ten years was one reason, as was a general shortage of money. In those days, the Commonwealth was dependent on handouts from the states. British insistence that the Royal Navy could do the job – provided Australia paid for it – confused the issue. It was not until 1904 that the first Director of Naval Forces, located in Melbourne, was appointed and proper consideration of what Australia needed in the way of naval defence commenced. Captain William Creswell stood resolute against the witterings of the chattering classes and the obdurate attempts by the British to discredit even the idea of an Australian navy.

It was tough work but he persisted, creating a growing body of informed opinion which included Alfred Deakin. Deakin approved the dispatch of our first naval mission overseas, which visited Japan, the USA and Britain in pursuit of a destroyer design that would meet Australia’s requirements. It was also Deakin who defied protocol and wrote to US President Theodore Roosevelt inviting him to include Australian ports in the itinerary of the Great White Fleet he was about to dispatch around the world. The visit in 1908 of 16 US battleships to Melbourne and other Australian cities did much to demonstrate the advantages of a modern Australian fleet responsive to the orders of the Australian government over the British ‘rent-a-navy’ scheme.

But help in Creswell’s struggle came also from the unlikely quarter of Imperial Germany, whose technological advances in warship design and construction and aggressive intent to use them to her advantage caused the British to rethink their naval strategy. Having Dominion adjuncts to the Royal Navy to patrol and police the farther-flung corners of the Empire became attractive and in 1909 British objections to an Australian navy were withdrawn. What emerged in its place was the ‘Fleet Unit’ concept, a piece of an Imperial navy that would be activated in time of war. The new River Class destroyers which Australia had ordered independently fitted nicely into this concept, one of them fittingly named Yarra. The man in London who had done the ordering was Captain Collins, the former Secretary for Defence in the Victorian colonial government.

A proper navy required a proper organisation to administer and operate it. The 1905 ‘Board of Naval Administration’, on which Creswell had been the only naval member, was replaced by the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board with three naval officers in its membership of five and a new home was required for the staff which, hitherto, had shared Victoria Barracks in St Kilda Road. Thus the first RAN headquarters was established at XX Lonsdale Street Melbourne in 1911, the year that saw Royal assent to the title ‘Royal Australian Navy’.

The new fleet under construction, which counted in its strength the light cruiser Melbourne, would require considerably more manpower than the new RAN actually had. Numbers had to be increased from 400 all ranks to nearly 3,500 in three years. Boy seamen were under training in Tingira in Sydney Harbour but adult entries, and especially technical sailors and officers, needed other facilities and Williamstown Naval Depot with the dockyard nearby met this need. It is likely that virtually every member of the growing RAN spent some time at Williamstown under training. Work on its successor – Flinders Naval Depot – commenced in 1913 but work was not completed until 1922.

The Naval Defence Act of 1909 authorised the foundation of a college to train officers of the Australian navy and from 1911 the Naval Board devoted great efforts to identifying a site and drawing up plans. Its final choice was Port Hacking near Sydney, a decision so politically insensitive that the Government was compelled to withdraw the proposal from parliament and to direct the RAN to build its college at Jervis Bay. Stunned, ACNB pointed out that it would have to go back to the drawing board and asked that interim arrangements be made to cover the delay this would cause in officer training. So it was that Osborne House near Geelong opened its doors to the illustrious first RANC entry in January 1913, and the college remained at Geelong until the Government demanded its shift to the unfinished Jervis Bay facility at the end of 1915.

When war came in August 1914 the RAN was ready in all respects, a remarkable achievement which has escaped public and even naval attention. The Fleet put to sea before war was declared, its target the German East Asiatic Squadron of modern cruisers based in China, thought to be operating in the waters of German New Guinea. The Navy took control of all Australian coastal wirelesses stations and reservists were called up to help man the fleet. Port Phillip Heads was to be the scene of two early dramas. The first occurred in the minutes after the declaration of war when the guns of Fort Lonsdale fired across the bows of the German steamer Pfalz, causing her to break off her attempt to leave the port. These are believed to be the first Allied shots fired in anger of the whole war, and Pfalz the first prize taken, becoming the Australian troop transport Boorara.

A few days later a RAN boarding party disguised as pilotage and customs officials seized the German ship Hobart when it entered Port Phillip, apparently unaware that war had been declared. By a subterfuge, the boarding officer was able to seize the ship’s German Navy merchant ship code books which provided much valuable intelligence to Room 40 in the Admiralty in London, and some interesting employment for the headmaster of RANC in deciphering and translating intercepted merchant ship traffic.

The first military action undertaken by the Australian Defence Force against a foreign power occurred on 11 September 1914 at Bita Paka near Rabaul, the site of the German colonial administration’s wireless station. The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force had been hurriedly cobbled together to undertake the task of ejecting the Germans, but it was naval personnel from the Fleet who fought this first action, gained our first our victory, won our first military decorations and, regrettably, suffered our first casualties. It probably comes as a complete surprise to all but a few Australians that the first fighting of World War 1took place in New Britain not Gallipoli, that it was sailors who fought it, not soldiers, and that we won, not lost. The strategic consequences of the victory are with us today; Gallipoli is a remembrance site. Amongst the dead at Bita Paka were the former term officer from the RANC at Geelong and two Victorian reservists.

And on the subject of Gallipoli, while the exploits of the RAN submarine AE-2, the first vessel to break through the Turkish defences into the Sea of Marmara, are possibly remembered at Anzac Day, it would be an unusual Australian who could recall the deployment and services of the RAN Bridging Train at Suvla Bay. The Bridging Train was originally formed from the Naval Brigade in Melbourne in 1915 and was bound for France, but was diverted to Gallipoli where it served the British Army with distinction, claiming the honour of being the last Allied unit to make its withdrawal from the peninsula. It served after that on the Suez Canal until disbanded in 1916.

The RAN operated in all seven seas during World War 1, and even afterwards in Russia, always with distinction, creating the traditions and reputations that today’s naval people strive to live up to. But I hope I have shed some light on the very strong influence that Victoria and Victorians had in making this possible in the earliest days of our navy’s history.

Contact Ian Pfennigwerth about this article.