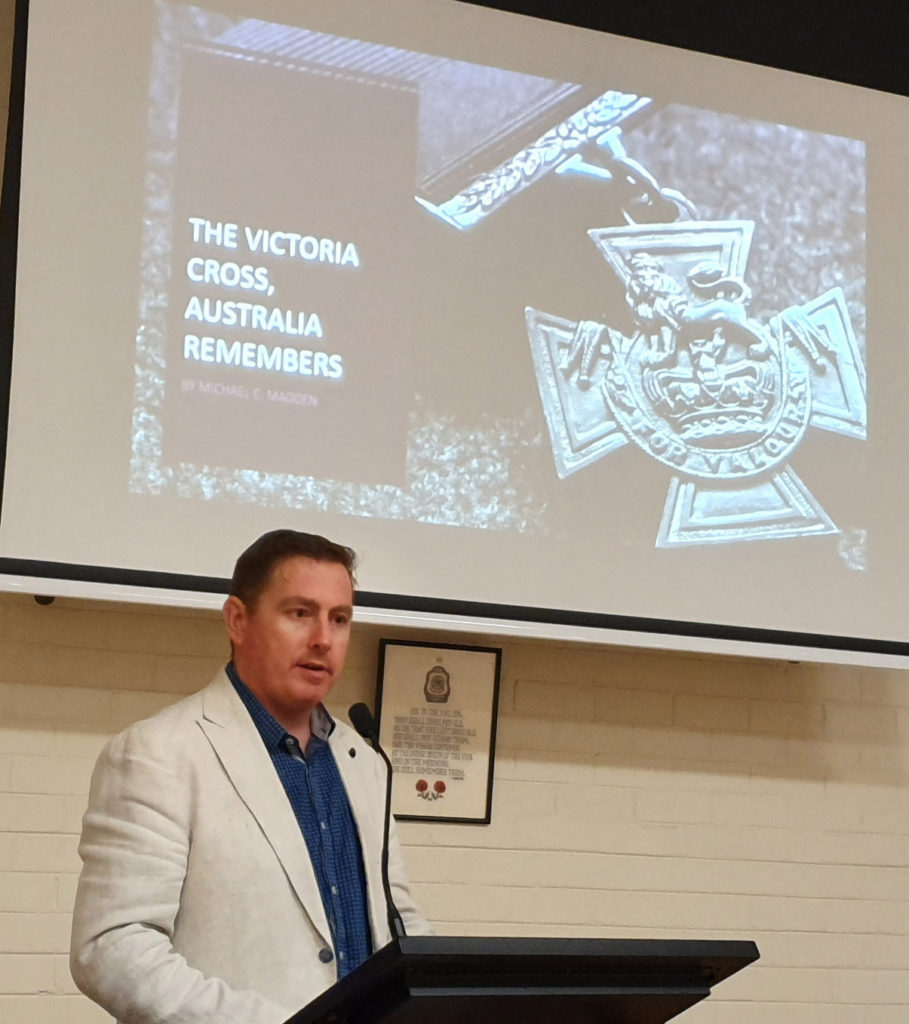

To set the scene, Michael began with a short video of interviews of family members of VC recipients taken while he was researching the book.

He began the formal part of presentation by confessing that he has been obsessed with the Victoria Cross medal the whole of his life. As a result he set out to write the book that he would like to read – a book that focussed on the human and family side of the 100 Australian servicemen that had been awarded the Victoria Cross since its inception in 1856.

The first Australian VC was awarded during the Boer War.

His journey to uncover and record the personal stories of all the Australian VC recipients spanned five years. His odyssey took him and his lead photographer, Gordon Triall, to 17 countries and all states and territories of Australia. They visited all the graves of the 96 deceased recipients as well as many of the statues and monuments around the world. At one point in his exhausting tour, Michael visited 22 sites in three days. Wherever they found graves in disrepair they fixed them if they could, but if not, notified the Australian War Graves Commission who arranged for their renovation.

They tracked down and photographed all 100 VC medals awarded to Australian soldiers. On a number of occasions he had to unearth the medals in long forgotten storage in peoples cellars. All are now in safe places, generally in museums and war memorials – which is just as well as an awarded medal is now worth over a million dollars.

His interviews covered 60 families – finding them was a difficult task in itself as there was not a register of addresses anywhere, not even at the Australian War Memorial.

He explained that the genesis of the VC medal was in the Crimean War. This was the first British war to be covered by reporters close to the front. Reports home made it clear that only officers received decorations. In contrast, their French allies awarded the Legion of Honour to any person irrespective of rank. This caused some agitation in Britain for common soldiers to be decorated for bravery.

Queen Victoria was very receptive to the notion and had a prototype made by Handcocks, her jeweller of the time. The British officers hated her prototype because, unlike the French medal, it was simple and plain. Most importantly, Queen Victoria loved the prototype and overrode all objections. The only changes she made was to replace the ‘For Bravery’ engraving to ‘For Valour’ and to make some modifications to the bronze hanging decorations on the ribbon.

At Queen Victoria’s insistence the Victoria Cross is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. The medal can only be conferred by the British sovereign and reflecting its status in the honour’s hierarchy, it always precedes any other award following a persons’ name. Recipients need to treat the honour with respect. There was an occasion in Australia at which a soldier arrived at an official function without his VC and was upbraided by the Governor General for disrespecting the Queen.

Queen Victoria’s interest in the common soldier was no passing fancy. She was deeply concerned about the lot of soldiers during the Crimean War. She back dated gazetting the VC to 1854 to recognise acts of valour during the Crimean War. She also wrote about common soldiers in her diary every day during the war. Michael was granted access to those diaries by Queen Elizabeth and spent three nights in the Royal archives reading them.

The medals are still made by Handcocks. The bronze is too hard and brittle to be made by stamping so they are sand cast. Each has a unique set of subtle markings that are recorded in a ledger and are used to verify any claims of authenticity. Finished, unawarded medals are stored in a vault below Handcocks’ shop. While the medal has remained relatively unchanged since 1856, there are subtle changes from time to time, principally to the central crown motif when the British sovereign changes.

The source metal for the VCs stored is stored in a high secure facility in Shropshire. There is a myth that the source metal was from the cascabels of two cannons captured from the Russians at the siege of Sevastopol. Metallurgical examination of the VCs at the Australian War Memorial and X-ray studies of older Victoria Crosses revealed the metal used for almost all VCs since December 1914 was taken from antique Chinese guns. Most likely these cannons were taken as trophies during the First Opium War and found in the Woolwich repository. The source of bronze for medals prior to 1914 is unrecorded except that it was from an earlier gun while a series of medals made during World War II were taken from another unknown source.

In concluding, Michael said that VC recipients, “Don’t do it for the honour. Don’t do it for king or country. They do it for their mates.”

In writing his book, Michael was assisted by volunteers from the Totally & Permanently Incapacitated Ex-Servicemen & Women’s Association of Victoria Inc. (TPI Victoria). The venture was supported by TPI. Big Sky Publishing published the book at cost and all proceeds from sales are returning to TPI. Michael noted that TPI had been ‘brilliant’ to his father, a Vietnam Veteran, with their support.

Around 35 attendees attended this fascinating discussion.

About the presenter

Born in Melbourne, Australia, Michael C Madden is the son of a Totally & Permanently Incapacitated Vietnam veteran. He enjoyed a modest but happy childhood; growing up with his three brothers on the family’s struggling dairy farm, before the family became homeless in the mid-1990s. Michael has a deep passion for writing and Australian military history. He runs a military medal business in Berwick, Victoria and has published four novels and many short stories.

Contact Brent D Taylor about this article.