Jeff Maynard has done Australia a great service by researching and writing this incredible biography of George Hubert Wilkins.

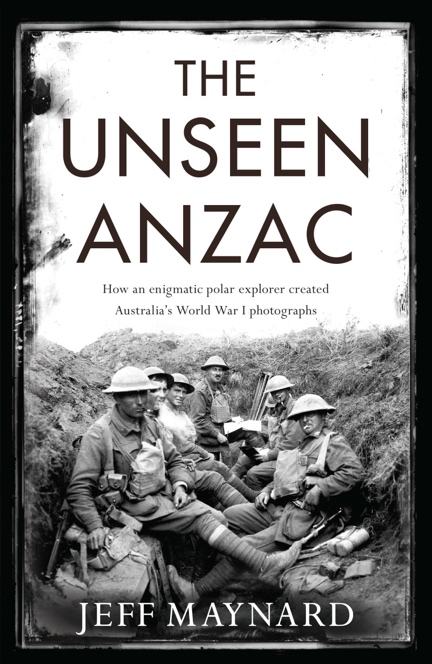

Cameras were banned at the Western Front when the Anzacs arrived in 1916, prompting war correspondent Charles Bean to argue continually for Australia to have a dedicated photographer. He was eventually assigned an enigmatic adventurer – George Hubert Wilkins, a reporter, filmmaker, photographer, arctic explorer and Balkan war correspondent before World War I (WWI). Working with Charles Bean, the result of his efforts is one of the most comprehensive records of any nation – a ‘minor national treasure’.

Within weeks of arriving at the front, Wilkins’ exploits were legendary. He did what no photographer had previously dared to do. He went ‘over the top’ with the troops and ran forward to photograph the actual fighting. Armed only with a bulky glass-plate camera, he led soldiers into battle, captured German prisoners and was wounded repeatedly. In June 1918, Wilkins was awarded the Military Cross for his efforts to rescue wounded soldiers during the Third Battle of Ypres (1917). Wilkins was awarded a bar to his Military Cross during the Battle of the Hindenburg Line (1918) when he assumed command of a group of American soldiers who had lost their officers in an earlier attack, directing them until support arrived.

Wilkins ultimately produced the most detailed and accurate collection of WWI photographs in the world, which is now held at the Australian War Memorial. Unfortunately, due to his modest nature, many iconic WWI photographs have been attributed to (or even claimed by) the self-promoting Frank Hurley. For example, the famous photograph of dazed Australian soldiers walking the duckboards through Chateau Wood on 29 October 1917 has always been credit to Hurley, when in fact Hurley’s diary reveals he was nowhere near Chateau Wood that day.

General Sir John Monash, the commander of the Australian Army Corps, described Wilkins as a “highly accomplished and absolutely fearless combat photographer. Wounded many times and even buried by shellfire, he always came through. At times he brought in the wounded, at other times he supplied vital intelligence of enemy activity. At one point he even rallied troops as a combat officer. His war record was unique.”

After the war, Wilkins returned to exploring and participated in a number of polar expeditions – including flights and submarine transits. He received awards from the Royal and American Geographical Societies. Wilkins flew from Alaska to Norway, for which he was knighted. In November 1928 and January 1929 he explored the Antarctic by air, and in the 1930s, made five further expeditions to the Antarctic. In 1931, he unsuccessfully attempted to take a WWI submarine, the Nautilus, under the Arctic ice to the North Pole. He subsequently worked in defence-related positions with the United States Weather Bureau and the Arctic Institute of North America.

Over time, Wilkins’ WWI exploits were forgotten and his personal life became shrouded in secrecy. He died in Framingham, Massachusetts, on 30 November 1958. He was so highly regarded in the United States that the US Navy later took his ashes to the North Pole aboard the submarine USS Skate on 17 March 1959. The Navy confirmed on 27 March that: “In a solemn memorial ceremony conducted by Skate shortly after surfacing, the ashes of Sir Hubert Wilkins were scattered at the North Pole in accordance with his last wishes”. The Wilkins Sound, Wilkins Coast and the Wilkins Ice Shelf in Antarctica are named after him.

Throughout his life, Wilkins wrote detailed diaries and letters, but when he died in 1958 these documents were locked away. Maynard follows a trail of myth and misinformation to locate Wilkins’ lost records and to reveal the remarkable, true story of Australia’s greatest war photographer.

Maynard continues to research Sir Hubert Wilkins and locate his records and artefacts in Australia, Europe, and the United States. “The legacy this man left this country is enormous and he risked his life to do so,” Maynard said. Wilkins’ exploits sound like a fantastical myth, and Maynard described Wilkins’ achievements with awe. “How do you measure the debt Australia owes Wilkins? After all these years, it’s time to acknowledge him.”

Maynard is an author and documentary maker. His books include Niagara’s Gold, Divers in Time, and Wings of Ice. He is a member of the Explorers Club of New York and is on the board of the Historical Diving Society.

The Unseen Anzac includes a good number of black and white images, a few well-produced maps and a series of break-out boxes examining the different tranches of photographs in the the Australian War Memorial’s collection. The book is organised into three parts – before, during and after the war. It includes a foreword by the Director of the Australian War Memorial – Dr Brendan Nelson – as well as a list of notes, a bibliography and an index. There is a list of acronyms as well as one appendix – a letter from Wilkins to his mother sent two weeks after he arrived on the Western Front.

The Unseen Anzac is an incredible story about a remarkable Australian and would be of interest to military history readers as well as those interested in 20th century exploration.

Contact Marcus Fielding about this article.