In 1859 Britain was swept with an anti-French fever whipped up by the Press as a result of the construction of the French warship La Gloire, the first armoured steam warship to be built.

In the same year the Palmerston government was forced by public opinion to set up a Royal Commission to review the defences of the United Kingdom. When the Commission reported in 1860 it recommended sweeping improvements to the defences of the Royal Dockyards at the enormous cost, in those days, of £11 million.

One result of the recommendations of the Commission was the construction of four sea forts to defend the Solent, the stretch of water between the Isle of Wight and Portsmouth. These were large circular forts, one sited on a spit of land off the Isle of Wight and the other three on shoal banks in the Solent. All were built of stone and partly clad with iron and all mounted some of the largest rifled muzzle-loading (RML) guns, 12.5-in 38 ton guns. At the same time a further fort was approved for the defence of Plymouth harbour. Known as the Breakwater Fort it was slightly smaller than the Solent forts and a revised, though abortive, design in 1866 included a pair of two-gun turrets on the roof of the fort.

The concept of mounting guns in turrets on coast defence forts was a very new one in the 1860s. Captain Cowper Coles RN had patented an iron revolving turret for two ‘heavy’ RML guns in 1859 and proposed the design of a number of turret ships for the Royal Navy. It was, therefore, a logical progression for British military engineers to suggest the mounting of turrets on coast defence forts.

These five forts were the only sea forts to be constructed by British military engineers. However, what is not generally known is that two similar sea forts and a tower with a turret for two guns were proposed for the defence of Melbourne in the 1860s though these were never constructed.

Melbourne Sea Forts

The Crimean War and the construction of the French armoured steam warship La Gloire produced war scares not only in Britain but also in the Australian colonies. The defences of Melbourne were rudimentary at this time with the main defences being an earth battery for nine 68-pounder smooth-bore guns at Williamstown and a battery of six guns at Sandridge.

In 1859 the Victoria government requested advice on the fortification of Melbourne from the War Office in London and in August 1860 Captain Peter Scratchley arrived with the specific task of reviewing the existing defences and advising on what additional defences were required. Scratchley’s recommendations included four batteries at the Heads at the entrance to Port Phillip Bay. In addition, he recommended the construction of five batteries at Sandridge and Williamstown to be reinforced by a floating battery and a wooden sea fort raised on piles in Hobson’s Bay. Despite a scare of war with the United States in 1861 only Scratchley’s proposals for the batteries for the close defence of Melbourne in Hobson’s Bay were completed in 1863 together with a battery at Shortland’s Bluff to defend the entrance to Port Phillip Bay.

Captain Scratchley returned to England in 1863 but plans for improving the defences of Melbourne and Port Phillip Bay continued with proposals in 1865 for the construction of towers at Point Nepean and Point Lonsdale to support HMVS Cerberus, the construction of which had recently been authorised. The Point Nepean tower was designed to carry a turret for two 23 ton RML guns (12-in Mk I). The cost of the tower was estimated at £10,000 with a further £10,000 for the turret and £8,000 for the armament making a grand total of £28,000 for the completed tower. (1). It is, perhaps, not surprising, therefore, that the construction of these towers was never authorised by the government of Victoria.

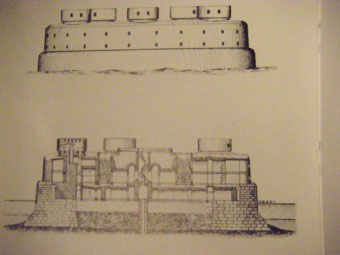

In London in 1867 the Defence Committee, under the chairmanship of Admiral Grey together with Rear Admiral Cooper Key and Lieutenant Colonel Jervois, reviewed further proposals for the defence of Melbourne and concurred with a report of the Fortifications Committee that two sea forts should be built for the defence of Port Phillip Bay. The forts were to be constructed in the water on a line between Point Gellibrand and Point Ormond, a distance of approximately 6,000 yards (5,538 metres), in order to provide a line of defence that was sufficiently advanced to protect Melbourne and its shipping from long-range guns. These forts were to be similar in design to the Breakwater Fort in Plymouth harbour but smaller in size.

One fort was to be sited on a shoal 500 yards (460 metres) from Point Gellibrand and this was to be an iron casemated fort mounting 10 x 9-in 12 ton RML guns in two tiers of casemates with 2 x 10-in 18 ton RML guns in a single turret. The second fort was to be sited in 4 ½ fathoms of water 2,000 yards (1,846 metres) from the Point Gellibrand fort. The second fort was to be more heavily armed mounting 12 x 9-in 12 ton RML guns in two tiers of casemates and 4 x 10-in 18 ton RML guns in two turrets.

The cost of the fort off Point Gellibrand was estimated at £75,000 for the foundations and iron casemates; £10,000 for the turret; £25,000 for the 9-in guns; and £7,000 for the 10-in guns. The total cost coming to £117,000. The cost of the deep-water fort was even more with an estimate of £145,000 for the foundations and iron casemates; £20,000 for the two turrets; £30,000 for the 9-in guns; and £14,000 for the 10-in guns. The total cost coming to the astronomical sum, for that time, of £209,000. (2.)

The proposals for the construction of the two sea forts came at a time when Britain was reviewing its Imperial defence policy and instituting a requirement that the dominions and colonies should contribute towards their own defence. At this time Britain was also considering the withdrawal of the Imperial garrisons from Canada and the Australian colonies and had passed an act of Parliament permitting the creation of official naval forces in the colonies. Having just authorised the construction of HMVS Cerberus the government of Victoria was not inclined to fund the construction of these expensive fortifications and so the project lapsed.

Notes:

- National Archives, Kew, London WO 33/18

- ibid.

Contact Bill Clements about this article.