As the centenary of the Great War has been observed, there has been considerable writing outside the realm of sacrifice, heroism and bravery emerging to redress the existing imbalance. A series of eight diverse papers examine conscription and its introduction in England, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, Newfoundland and Ireland and the referenda of 1916 and 1917 in Australia.

Paperback 259pp RRP: $34.95

Australia and New Zealand introduced compulsory military training for males from 12 to 25 years of age in 1911 whereas other Allies did not. Limited conscription was legislated in these countries, and Australia’s PM Billie Hughes was in Britain in early 1916 when it was introduced there. Knowing he would not have the support of his party, Hughes opted for referenda on 28 October 1916 and 20 December 1917 to introduce conscription – being without precedent in the English-speaking world and to be narrowly defeated on both occasions. Political turmoil became the order of the day, with incredibly acrimonious claims being made by both ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ campaigners. Some described it as a ‘sort of civil war’.

Robin Archer examines the origin of the Referendum, while the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ supporters, their arguments and support bases are dealt with in separate papers. In a country already under strict wartime measures and censorship there was fear of the militarization of industry by Labor supporters and farmers seeing their labourers disappear. Those who had husbands or sons already serving overseas considered ‘No’ supporters to be little short of traitors.

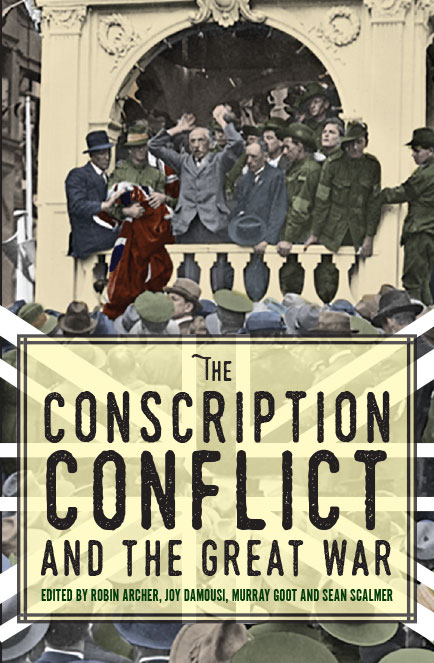

The photographs provided demonstrate the influence women had on the campaigns, and the cartoons included depict the level to which both sides stooped to put their point of view. [It would appear that nothing has changed in 100 years!]

Murray Goot has examined the results in detail to the best of information available. Indicative of the strong feelings of the Australian community there was greater than 80% turnout on both occasions (compulsory voting not being introduced until 1924). State-by state turnouts for four referenda post Federation and before 1916 and one held in 1919 reinforce this claim. State voting patterns, by party and metropolitan versus rural electorates are tabled without any ‘long bow’ conclusions being drawn.

John Connor’s paper examines why conscription was easier to introduce in the countries mentioned above, compared with Australia. In all cases the circumstances were different, and acceptance was not necessarily a bitter pill to swallow. For some countries, conscription was too late to be actioned to any degree. Ross McKibbin looks at why conscription was accepted in Britain, while the issue remained nation dividing here in Australia.

Australian politics post-Great War have been summarised in the final chapter and examine the different philosophies that prevailed until the Menzies’ government introduced conscription in 1966 during the Vietnam War.

An excellent and well-balanced examination of one of the major issues that confronted our young nation – indicating that there was far more to the Great War than simply farewelling our brave youth and praying they would be safely returned to our shores.

Reviewed for RUSIV by Neville Taylor, November 2017

Contact Royal United Services Institute about this article.