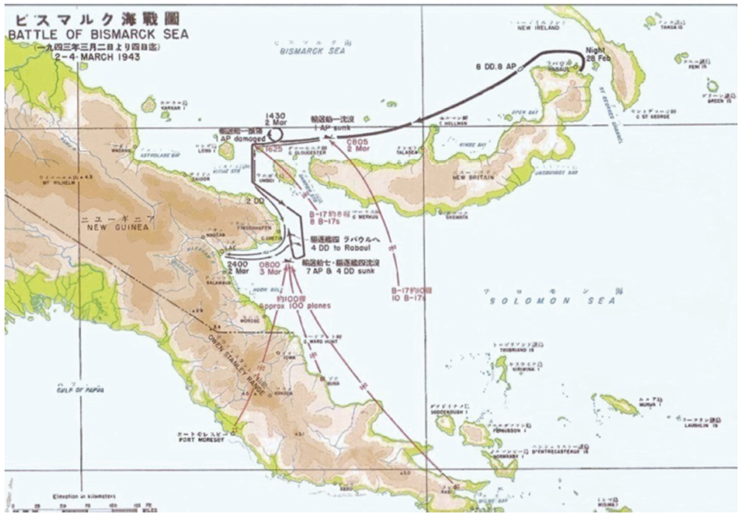

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea was fought on 2-4 March 1943 largely in the Bismarck Sea and the Vitiaz Strait (between New Britain and New Guinea). The United States Army’s 5th Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force attacked an Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) convoy attempting to transport 6900 Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) reinforcements from Rabaul (New Britain) to Lae (New Guinea). Eight IJN transport ships, four of eight escorting IJN destroyers and 20 of 100 escorting IJN fighter aircraft were destroyed for the loss of four Allied aircraft. Of the IJA reinforcements, 1200 reached Lae, 3000 perished at sea and 2700 were rescued by the IJN and returned to Rabaul.

The historian, Lex McAulay, has described the Battle of the Bismarck Sea (2-4 March 1943), as “thirty minutes that changed the balance of power in New Guinea”; and as “a battle for land forces, fought at sea, won by air” (McAulay 1991).

The battle took place in the South-West Pacific Area (SWPA) during World War II when aircraft of the United States Army’s 5th Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force attacked a Japanese convoy carrying troops from the Japanese fortress at Rabaul in New Britain to Lae in New Guinea. Most of the Japanese task force was destroyed and Japanese troop losses were heavy (Odgers 1957; McCarthy 1959; Tanaka 1980; McAulay 1991).

By early 1943, Imperial Japan had established its ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere’, but its attempts to isolate Australia and prevent its use as base for an American-led counter offensive had been repulsed by the United States and Australian armed forces. The naval battles, won largely by naval air power, in the Coral Sea (4-8 May 1942) and at Midway (4-7 June 1942), had greatly reduced the offensive power of the Imperial Japanese Navy and had saved Port Moresby, capital of Papua, from naval assault. The land battles in Papua – at Milne Bay (25 September-7 August 1942), along the Kokoda Trail (July-November 1942) and at Buna-Gona (16 November 1942-22 January 1943) – had prevented the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) from consolidating its foothold in Papua and most of its forces there had been withdrawn to New

Guinea or New Britain. In the Solomon Islands, American forces had triumphed in the battle for Guadalcanal (7 August 1942 9 February 1943) and the IJA had withdrawn its forces north to Bougainville in the northern Solomons (McCarthy 1959).

The Allied position having been stabilised in Papua and the southern Solomons, the way was now open for a counter offensive to be launched from Australia towards the northern Solomons, New Guinea and New Britain, with a view to either capturing or isolating Rabaul, the main Japanese base, and then advancing by bounds (sites with suitable airfields and harbours) to the Philippines.

Recognising this threat, the Japanese decided to reinforce its naval, land and air forces in New Britain, New Guinea and the northern Solomons in an attempt to check the anticipated Allied advances.

Japanese Plans for the Battle

Japanese Imperial General Headquarters decided in December 1942 to reinforce the Japanese position in New Guinea, particularly at Wewak, Madang and Lae. A plan was devised to move some 6900 troops by naval convoy from Rabaul to Lae (Tanaka 1980; Nelson 1994).

In late February 1943, the Japanese assembled a convoy comprising eight troop transports, escorted by eight destroyers, some submarines, and approximately 100 fighter aircraft. The convoy was planned to set out from Simpson Harbour, Rabaul, on 28 February 1943, steam west through the Bismarck Sea along the north coast of New Britain, before turning south through the Vitiaz Strait to the Solomon Sea and thence west to Lae.

Allied Plans for the Battle

The Allies gained an inkling of the Japanese plans when, on 16 February 1943, naval codebreakers at Fleet Radio Unit, Melbourne, and in Washington finished decrypting and translating a coded message revealing the Japanese intention to land convoys on the north-east coast of New Guinea at Wewak, Madang and Lae (McCarthy 1959: 582; McAulay 1991).

To counter this threat, the Allies assembled an air armada comprising three attack groups and three bombardment groups from the United States Army’s 5th Air Force (5th USAAF) and seven squadrons of fighters and bombers from the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) under the command of Lieutenant General George C. Kenney, USAAF (Morrison 1950).

The 5th USAAF contribution was based at Buna, Milne Bay, Mareeba (North Queensland) and Port Moresby. It comprised the: • 35th Fighter Group (P-38 Lightning; P-39 Airacobra); 49th Fighter Group (P-38 Lightning; P-40 Warhawk).

• 3rd Attack Group (A-20 Havoc bomber; B-25 Mitchell bomber).

• 38th Bombardment Group (B-25 Mitchell bomber), each bomber with a crew of five and a bomb load of 3000lb (1360kg).

• 43rd Bombardment Group (B-17 Flying Fortress bomber), each bomber with 10 crew and a bomb load of 8000lb (3600kg).

• 90th Bombardment Group (B-24 Liberator bomber), each bomber with a crew of 11 and a bomb load of 8000lb (3600kg); and

• 8th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron (F-4 and F-5 Lightning photo reconnaissance aircraft).

The RAAF assembled four squadrons at Milne Bay and three at Port Moresby. At Milne Bay were:

• No. 6 Squadron (Hudson bomber).

• No. 74 Squadron (P-40 Kittyhawk fighter and ground-attack aircraft).

• No. 75 Squadron (P-40 Kittyhawk fighter and ground attack aircraft); and

• No. 100 Squadron (Beaufort torpedo-bomber).

At Port Moresby were:

• No. 4 Squadron (Wirraway trainer and general-purpose military aircraft).

• No. 22 Squadron (Boston bomber and ground attack aircraft); and

• No. 30 Squadron (Beaufighter multi-role military aircraft).

The Beaufort torpedo-bomber had a crew of four; and a bomb load of one 1605lb (728kg) bomb and an 18-inch Mark XII torpedo, or 2000lb (907kg) of bombs or mines. The Boston bomber had a crew of three and a 4000lb (1800kg) load of bombs. The Beaufighter had a crew of two; and two 250lb (110kg) bombs, or one British 18- inch torpedo, or one United States Mark XIII torpedo.

The commander of the Allied Air Forces in the South West Pacific Area, Lieutenant General George C. Kenney, USAAF, decided on an all-out assault on the convoy. The plan was prepared by Group Captain William ‘Bull’ Garing, RAAF, and involved a massive, co-ordinated attack. Garing envisaged large numbers of aircraft striking the convoy from different directions and altitudes with precise timing. Recon naissance aircraft would detect the convoy; then long-range USAAF bombers would attack it. Once the convoy was within range of the Allies potent anti-shipping aircraft – RAAF Beaufighters, Bostons and Beauforts and USAAF Mitchells and Bostons – a co-ordinated attack would be mounted from medium, low, and very-low altitudes.

Bombing tactics would include both skip bombing and mast-height bombing. Skip bombing involved bombers flying at very-low altitude (only a few dozen feet above the sea – maybe 15-20m) toward their targets before releasing their bombs which would ricochet (bounce) across the surface before exploding at the side of the target ship, under it, or just over it. Mast-height bombing involved bombers approaching the target at low altitude, 200 to 500 feet (60-150m), at about 265 to 275 miles per hour (425-440km/h), and then dropping down to mast height at about 600 yards (550m) from the target, before releasing their bombs at around 300 yards (275m) while aiming directly at the side of the ship.

The Battle

On the night of 28 February-1 March 1943, a convoy of 16 ships (eight destroyers, seven transports and the special service vessel Nojima) steamed from Simpson Harbour, Rabaul, bound for Lae to reinforce the Lae-Salamaua garrison. The reinforcements mainly comprised the second echelon of the Japanese 51st Division (McCarthy 1959: 582).

The weather initially aided the Japanese. About 15:00h on 1 March, the crew of a patrolling B-24 Liberator spotted the IJN convoy in the Bismarck Sea north of New Britain. Eight B-17 Flying Fortresses subsequently sent to the location failed to find the IJN ships, so no attack could be pressed home until the next day (McCarthy 1959: 582).

At dawn on 2 March, a force of six RAAF A-20 Bostons from Port Moresby attacked Lae to reduce its ability to provide fighter cover for the IJN convoy. About 10:00h, another Liberator found the IJN convoy in the Bismarck Sea north of Cape Gloucester at the western end of New Britain (Map 2). Eight B-17s took off to attack the ships, followed an hour later by another 20 B-17 bombers. They found the convoy and attacked with 1000lb (450kg) bombs from 5000ft (1500m). By nightfall, there were reports of ships “burning and exploding”. It later emerged that the Kyokusei Maru,

carrying1200 army troops, had been sunk and two other transports damaged; and eight Japanese fighter aircraft destroyed and 13 damaged. Through the night, an Australian Catalina shadowed the fleet (McCarthy 1959: 582).

The main planned Allied attacked on the convoy occurred on 3 March 1943 (McCarthy 1959: 582) and some authorities give this day as the date of the battle, e.g., McAulay (1991), “thirty minutes that changed the balance of power in New Guinea”, quoted earlier.

Beginning early on 3 March, Bostons of No. 22 Squadron, RAAF, from Port Moresby again attacked the Japanese fighter base at Lae, further reducing the convoy’s air cover. Attacks on the base continued throughout the day.

At 10:00h, 13 B-17s reached the convoy, now entering the Vitiaz Strait off the Huon Peninsula, and bombed from a medium altitude of 7000ft causing the ships to manoeuvre. This had the effect of disrupting the convoy’s formation and reducing the convoy’s concentrated anti-aircraft firepower. Nevertheless, a B-17 was hit. It broke up in the air and its crew took to their parachutes. Japanese fighter pilots machine-gunned some of the B-17 crew members as they descended and attacked others in the water after they landed. Five of the Japanese fighters strafing the B-17 aircrew were promptly engaged and shot down by three Lightnings (Craven and Cate 1950).

Shortly after, some B-25 bombers arrived and released their 500lb bombs at between 3000 and 6000 feet (900-1800m), causing two Japanese vessels to collide. By the end of their attack runs, the B-17 and B-25 sorties had left the convoy ships separated, making them vulnerable to strafing and mast-head attacks.

Thirteen Beaufighters from No. 30 Squadron, RAAF, approached the convoy at low level to give the impression they were Beauforts making a torpedo attack. The ships turned to face them, the standard procedure to present a smaller target to torpedo bombers, allowing the Beaufighters, with flights in line astern, to maximise the damage they inflicted in strafing runs (Craven and Cate1950: 143-4). The famous Australian combat cameraman Damien Parer accompanied the raid. He sat behind the pilot of one of the Australian Beaufighters and captured the attack scenes on film2. Immediately afterwards, seven B-25s of the 71st Bombardment Squadron bombed from about 2460ft (750m), while six from the 405th Bombardment Squadron attacked at mast height inflicting further damage. “And then came 12 of the 90th [Bombardment Group’s] B-25 Mitchels in probably the most successful attack of all. Coming down to 500 feet above the now widely dispersed and rapidly manoeuvring vessels, the new strafers broke formation as each pilot sought his own targets” (Craven and Cate 1950: 143-4).

More flights sallied out from Port Moresby in the afternoon, but although they had some successes, bad weather over the Owen Stanley Range reduced the planned size of the attacking force. Still, the close of day found the work done. That night, motor torpedo (PT) boats swept out of their base at Tufi (on the northeast coast of Papua – Map 1) to undertake cleaning up tasks which they largely completed on 4 March (McCarthy1959: 582-3).

The Allied air commander was given intelligence on 4 March that, despite their transport ships and some of their escorting destroyers having been sunk, hundreds of Japanese soldiers and sailors had survived the air attacks of 2 and 3 March and the survivors were awaiting rescue at sea. He ordered the Allied airmen to do everything they could to attack these Japanese survivors with a view to preventing them from getting ashore and reinforcing the IJA forces at Lae (McAulay 1991: Chapter 5).

Over succeeding days, strafing aircraft at sea level gunned survivors; and garrisons in the Trobriands and on Goodenough Island hunted down and killed survivors cast up by the sea (McCarthy 1959: 583; McAulay 1991: Chapter 5). These ‘mopping up’ operations on 4 March and subsequent days concluded the battle.

In total, during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, the Japanese had lost all eight transport ships, four of their eight destroyers and 20 aircraft. Of the Japanese re enforcements, 1200 reached Lae, 3000 perished at sea and 2700 were rescued by IJN destroyers and submarines and were returned to Rabaul (Tanaka 1980: 50). The Allies lost four aircraft and 13 airmen (Nelson 1994).

Conclusion

As brilliant and extensive as this Allied victory was, its real lesson lay in in the significance of Allied air power (McCarthy 1959: 583). The success of Allied airpower during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea convinced the Japanese that even strongly escorted convoys could not operate without air superiority. This they could no longer generate. In the absence of air superiority, the Japanese were unable to reinforce, resupply and otherwise logistically support their forces in the region other than by small ships, patrol boats and submarines.

As a result, the Japanese were permanently put on the defensive in the northern Solomons, New Guinea and New Britain. This opened the way for the Japanese fortress at Rabaul, garrisoned by some 100,000 personnel and deemed impregnable, to be isolated and bypassed. This, in turn, enabled successful Allied campaigns along the New Guinea coast and on to the Philippines over the next 18 months.

Lieutenant Colonel Peter Sweeney RFD (Ret’d) – A paper based on an online presentation to the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, New South Wales1 on 29 September 2020

The Author: Lieutenant Colonel Peter Sweeney RFD (Ret’d) has been a member of the Institute since 1968. A military historian and a member of the United Kingdom based International Guild of Battlefield Guides, he is in partnership with fellow Institute historian, Lieutenant Colonel Ron Lyons RFD (Ret’d), in the battlefield touring company, Battle Honours Australia. He holds a Master of Military History degree from the University of New South Wales, a Graduate Diploma in Management (Defence Studies) and a Diploma in Accounting. He is a noted presenter to community groups on Australian military history; and travels from time-to-time on cruise ships as an enrichment speaker on naval, army and air force history. [Photo of Colonel Sweeney: the author]

Acknowledgement

I thank Dr David Leece for helpful comment on the manuscript.

References

Craven, W. F., and Cate, J. L. (1950). The Army Air Forces in World War II, Volume 4.

Odgers, George (1957). Air war against Japan, 1943-45. Australia in the War of 1939-45, Series 3 (Air), Volume II (Australian War Memorial: Canberra).

Nelson, H. W. (1994). Reports of General MacArthur: Japanese operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, Volume II – facsimile printing (United States Department of the Army).

McAulay, Lex (1991). The battle of the Bismarck Sea (St Martin’s Press: New York).

McCarthy, Dudley (1959). South-West Pacific Area – first year; Kokoda to Wau. Australia in the War of 1939-45, Series 1 (Army), Volume V (Australian War Memorial: Canberra).

Morrison, S. E. (1950). Breaking the Bismarck barrier. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (Little Brown and Company: Boston).

Tanaka, Kengoro (1980). Operations of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces in the Papua New Guinea Theatre during World War II (Papua New Guinea Goodwill Society: Tokyo).

Contact Royal United Services Institute about this article.