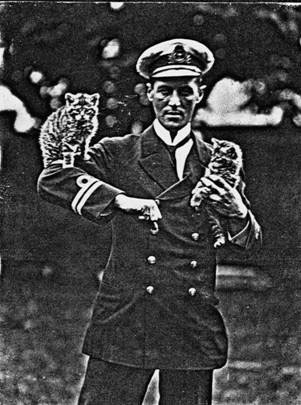

Captain Robert Alexander (Alec) Little, our greatest fighter ace, has fallen off our radar of almost all Australians.

Today it is usually only WWI aviation enthusiasts and students at Scotch College, Melbourne, his old school, who recall the remarkable record of the young Melbourne pilot who claimed 47 victories and won a chestful of medals before his death at 22 in May 1918.

Melbourne writer Mike Rosel (a MHHV member) hopes that publication of his Little biography—UNKNOWN WARRIOR: The search for Australia’s greatest ace—may win Little wider recognition.

Little’s formidable achievements with the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) meant that he is not on the commemorative walls at the Australian War Memorial (AWM) reserved for those who died in Australian units. Alec is one of seven Australians listed in the AWM Commemorative Book (a Roll of Honour of those who served in non-Australian forces) as having been killed flying with the RNAS during the First World War.

His medals (DSO and Bar, DSC and Bar and Croix de Guerre) temporary Celtic cross marker and other memorabilia were donated by descendants to the AWM in 1978. Medals and cross are prominently displayed opposite relics of Baron von Richthofen, whose pilots he faced above the Western Front.

Little’s father, a Canadian of Scots descent, came to Melbourne in the late 1880s and became an importer of medical textbooks. Alec, one of four children, was born in Hawthorn in 1895. He and his younger brother James attended Scotch College, where he failed to impress academically, leaving school while still 15 to join his father as a commercial traveller. At school he took extra lessons in boxing and French; his fighting spirit was confirmed in battle, and even schoolboy French would have been useful seeking entertainment behind the lines. There’s no evidence to confirm one story that Alec painted his Sopwith Triplane in Scotch College colours, although it appears he did (once only, as a young pilot) fly with the school colours fluttering from his wingtips.

Alec always wanted to fly, descendants say. He was 14 when the showman Harry Houdini, best known as the great escapologist, became an Australia celebrity as the first man to fly in Australia, at Diggers Rest just outside Melbourne.

Given the Imperial indoctrination of the age (a Scotch College historian described the school as ‘ultra-Imperialistic’), it is no surprise that Alec Little wanted to join the tens of thousands volunteering to fight. Unsuccessful in an attempt to join our infant air force, he was still a teenager when he planned to sail P&O to London in July 1915.

He paid a hundred pounds to learn to fly at Hendon in northwest London, then volunteered for the Royal Naval Air Service. He quickly earned the ire of his superiors: ‘As an officer is not very good, and has a bad manner’ was one comment on his service file. He also earned a reputation for luck, racking up a startling number of forced landings, some due to poor flying or inattention, most the fault of poor quality training aircraft and primitive engines. Another file annotation: ‘Has a trick of landing outside the aerodrome.’

Assigned to pilot seaplanes, which did not appeal, he was threatened with loss of his commission unless he shaped up. He did so. He was having more success with his courting of Vera Field, a young woman from Dover.

Alec later joined some bombing raids from Dunkirk in a Bristol Scout. He escaped seaplane duty after the Navy decided to contribute squadrons to Western Front duty during the Somme offensive. He was assigned to Naval Eight squadron.

Notwithstanding health concerns including measles, a month in hospital with pleurisy (he married Vera during convalescence) and nausea from the castor oil fumes from rotary engines, he quickly proved himself a formidable combat pilot, claiming four victories in his Sopwith Pup by the end of 1916.

The fighting which followed the Arras offensive of 1917 confirmed him as one of the war’s great aces. In July he claimed 14 victories in his Sopwith Triplane which flaunted his son’s nickname—Blymp—boldly beneath his cockpit.

He fought so effectively on the Lens-Arras front that his fellows nicknamed him ‘Rikki’ after the lethal cobra-killing mongoose in Rudyard Kipling’s hugely popular The Jungle Book. He enjoyed hunting solo, often being the last to return.

Postwar, his former Commanding Officer eulogised him in the squadron history Naval Eight: ‘Little was just an average sort of pilot, with tremendous bravery. Air fighting seemed to him to be just a gloriously exhilarating sport…he never ceased to look for trouble, and in combat his dashing methods, close range fire and deadly aim made him a formidable opponent, and he was the most chivalrous of warriors. As a man, he was a most lovable character.’

The Australian Dictionary of Biography entry describes him as ‘likeable and friendly with a strong sense of fun; he was a great talker.’ A brilliant shot, he often wandered with colleagues on the fringes of the grass airfields, seeking other game. He collected wildflowers.

His service record changed dramatically to speak of a ‘brilliant fighting pilot…exceptional courage and gallantry…flight leader of great daring’ and more.

He pushed his luck and aircraft to the limit, preferring to fire at cricket-pitch range, often noted as diving faster than colleagues who had justified concerns for the Triplane’s fragility. He’d been known to land behind Allied lines to clear a jammed Vickers machinegun before resuming the solo hunt.

A descendant characterised him as ‘brave, but reckless’. On 7 April 1917 he fought in solo combat against 11 Germans; British anti-aircraft gunners reported how the Triplane had completely outmanoeuvred the enemy, who finally gave up.

His luck was never more tested than on 2 April 1918 after he shot down the last Pfalz scout from a formation of 12. His combat report continues:

I was then attacked by six other E.A. (enemy aircraft) which drove me down through the formation below me. I spun but had my controls shot away and my machine dived. At 100ft from the ground it flattened out with a jerk, breaking the fuselage just behind my seat. I undid the belt and when the machine struck the ground I was thrown clear. The E.A. still fired at me while I was on the ground. I fired my revolver at one which came down to about 30 ft. They were driven off by rifle and machine gun fire from our troops.

Not only had been shot down for the first time, but he’d been thrown into a manure heap, as a fellow pilot revealed decades later: hence the recklessness of firing his revolver at aircraft with twin machineguns.

Little’s meteoric career ended on 27 May 1918. Acting as Squadron Leader of 203 Squadron (the Royal Air Force had been formed on 1 April), he took off from Ezil le Hamel in a solo night search for a Gotha bomber. His crashed Camel was found next morning near Noeux. Little had been fatally wounded in the groin, his CO reported. Nobody has established what happened that night. It may even have been ‘friendly fire’.

He was buried behind a Casualty Clearing Station at Wavans in the Pas de Calais region. Given his lack of recognition, there is an irony in the famed British ace James McCudden VC being in the front row of 44 headstones, while Little is at the rear.

Little is ranked eighth of British Commonwealth Aces in the Great War. Remarkably, the Sopwith Pup (Lady Maud) in which he claimed his first four victories is displayed at the Royal Air Force Museum in London, although it is not identified as his. A former Royal Navy pilot acquired Lady Maud in pieces from a French hangar and spent a decade in restoration. It was briefly flown at a commemoration in the 70s.

Alec and Vera had agreed that if he was killed, she and their son would settle in Melbourne with the help of Little’s family. This duly happened. Vera remarried in the 1920s; Alec junior grew up to head the electronics laboratory at Melbourne university. He never married, living with his mother until his death in 1976. Vera died a year later.

Lest we Forget? Alec Little has been largely forgotten, notwithstanding some formal memorialisation, including the somewhat ironic commemoration of Little and his friend and fellow RNAS Ace Roderic (Stan) Dallas with adjacent dead-end streets named after them in the Canberra suburb of Scullin. Dallas, a personal friend, died in combat with three German triplanes five days after Little’s death.

Contact Mike Rosel about this article.