Passchendaele epitomises everything that was most terrible about the Western Front: “pointless butchery that, even by the standards of the Great War entered the realm of the infernal and monumentally futile”. Soldiers, animals, artillery and pouring, unrelenting rain were “thrown together in a maelstrom of steel and flesh in the name of a strategy that anticipated hundreds of thousands of casualties – and all for nothing”. The battles at and around the small Flemish town were fought from July to November 1917 and as we approach the 100th anniversary of the battle, it is surely time, as Paul Ham has done in Passchendaele, to attempt a new understanding of a campaign that has inspired so much righteous indignation and passionate debate.

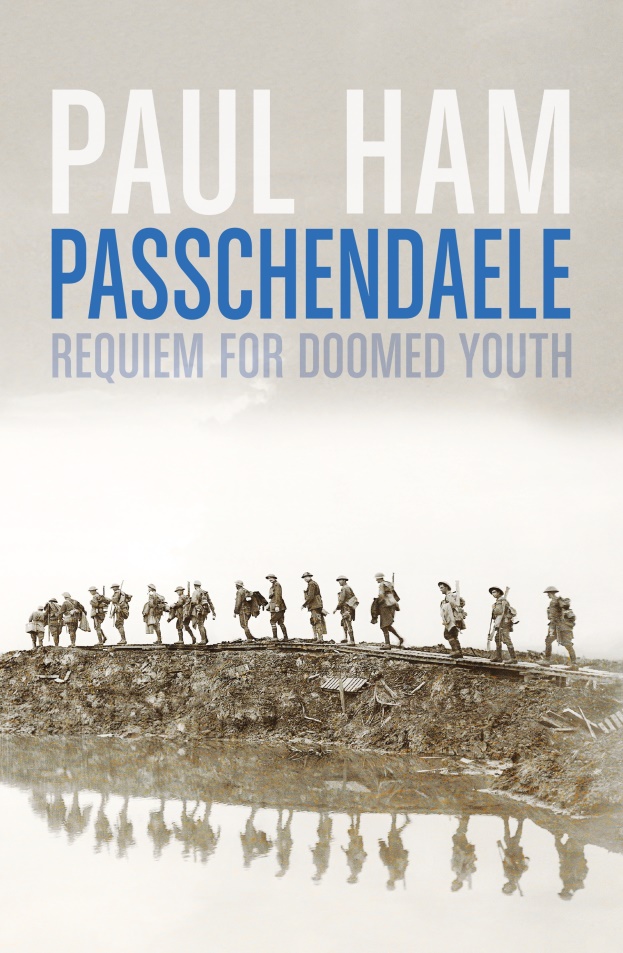

Photographs of this four-month battle show blackened tree stumps rising out of a field of mud, corpses of men and horses drowned in shell holes, terrified soldiers huddled in trenches awaiting the whistle call to go ‘over the top’. The intervening century has not disarmed these pictures of their power to shock. At the very least they ask us to see and to try to understand what happened here.

The British general who conceived the battle was Field Marshal Douglas Haig, commander of British and Australian forces on the Western Front for much of the war. Haig was certain the war would have to be won by ‘wearing them down’, and breaking their will. This resulted in an orgy of annihilation in which tens of thousands of young men died in the mud.

Passchendaele shows how ordinary men on both sides endured this constant state of siege, with a very real awareness that they were being gradually, deliberately, wiped out. Yet the men never broke: they went over the top, when ordered, again and again and again. And if they fell dead or wounded, they were casualties in the ‘normal wastage’ of attritional war. As Ham points out, the battles of Passchendaele “ravaged the morale of the British and Dominion soldiers, whose spirit fell into the darkest slough of despond since the war began”.

Passchendaele reveals details of the bizarre and terrible scenes on the battlefield that literally drove men mad. Ham lays bare the secret political contest between Haig and his prime minister, David Lloyd George, and lays down a powerful challenge to the idea of war as an inevitable expression of the human will by critically examining the culpability of governments and military commanders in a catastrophe that destroyed the best part of a generation.

In one of the book’s key chapters, titled ‘What the Living Said’, Ham directly addresses this controversy and, in particular, asks: “Was Passchendaele worth it?’’ “How did it contribute to the final victory, if at all?” And finally, the vexed question: “Should it have been fought in the first place?” Ham undertakes a detailed critical analysis of the different perspectives and his conclusions are well founded and damning.

Unsurprisingly, Haig’s reputation as a courageous commander and clever strategist was, and is, questioned by many historians and observers. Indeed in late 1917, Lloyd George, appalled by the litany of losses, tried to transfer command of the British army to the French, to sidestep Haig. Lloyd George revealed in his war memoirs published in the 1930s: “Whilst hundreds of thousands were being destroyed in the insane egotism of Passchendaele, every message or memorandum from Haig was full of these insistences on the importance of sending him more men to replace those he had sent to die in the mud”. In fact, Lloyd George even claimed that “the Passchendaele fiasco imperilled the chances of final victory”.

Ham’s intricately argued and finely researched book draws a number of blunt and incisive conclusions. Much of the evidence now suggests that, during the time of his command, Haig’s forces were wiped out at a far higher rate than the German troops.

Ham is a historian specialising in 20th century conflict, war and politics. His books have been published to critical acclaim in Australia, Britain and the United States. He walked the fields of Passchendaele and combed through the available records of the conflict. Written with the aid of three researchers – Glenda Lynch in Australia, Simon Fowler in Britain and Elena Vogt in Germany – Passchendaele explores the interwoven lives and deaths of British, Australian, New Zealand, Canadian, German and other soldiers who participated in this terrible conflict. The book includes eight clear maps and a good number of images. There are nine useful appendices as well as comprehensive notes, bibliography and index.

In Richard Aldington’s brilliant 1929 autobiographical novel about the war, Death of a Hero, he writes of “the lost millions of years of life” and suggests, “We have to make those dead acceptable … we have to appease them”. But as to how, he is unsure. “I know”, Aldington writes, “there’s the Two Minutes Silence. But after all, two minutes of silence once a year isn’t much.” Adlington concluded that, “Somehow we must atone to the dead”. In his own way, in Passchendaele: Requiem for Doomed Youth, the prolific and talented Paul Ham is doing just that.

Contact Marcus Fielding about this article.