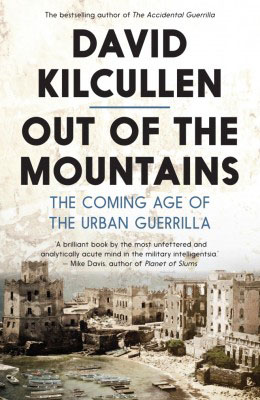

by David Kilcullen, Scribe Publications Pty Ltd, 2013; 368 pp.; ISBN 9781922070678 (paperback); RRP $32.95

David Kilcullen is a former Australian Army officer who holds a PhD in political anthropology and has been an Adjunct Professor of Security Studies at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He has served in East Timor, Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia. He has been a counterinsurgency advisor to US Army Generals David Petraeus and Stanley McChrystal, as well as to US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice.

Kilcullen is presently the founding president and CEO of Caerus, a Washington-based consulting firm that specialises in economic development, violent conflict, humanitarian assistance, energy shortage and climate change.

Kilcullen is regarded as one of the world’s foremost thinkers on counterinsurgency and the nature of modern warfare. His previous books include The Accidental Guerilla, which was a Washington Post bestseller, and Counterinsurgency. In Counterinsurgency, Kilcullen argued that successful counterinsurgency is about out-governing the enemy and winning the adaptation battle to provide integrated measures to defeat insurgent tactics through political, administrative, military, economic, psychological and informational means.

In Out of the Mountains, Kilcullen explores the broader notion of ‘conflict ethnography’ – “a deep, situation-specific understanding of the human, social and cultural dimensions of a conflict, understood not by analogy with some other conflict, but in its own terms.” Kilcullen analyses four megatrends – urbanization, littoralization, population growth and connectedness – and concludes that future conflict is increasingly likely to occur in sprawling coastal cities, in underdeveloped regions of the Middle East, Africa, Latin America and Asia, and in highly networked, connected settings. He sees that agents employing coercion and violence will become more pronounced in cities where they will compete to control groups of people. This deduction is not dissimilar to that reached by Robert Kaplan, Charles Krulak, Thomas P.M. Barnett and William Lind over the last decade. Kilcullen does, however, bring fresh perspectives on the increasing overlaps between crime and war, internal and external security threats, and the real and virtual worlds.

Informed by his own fieldwork in the Caribbean, Somalia, the Middle East, Afghanistan, and that of his field research team in cities in Central America and Africa, Out of the Mountains presents detailed, on-the-ground accounts of the faces of modern conflict – from the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks, to transnational drug networks, local street gangs, and the uprisings of the Arab Spring. Despite being intimately involved in the campaign Kilcullen seems to downplay examples from the war in Iraq despite the fact that it is largely landlocked yet one of the most urbanised countries in the world.

Kilcullen also explores what national governments, cities, communities and businesses can do to prepare for a future in which all aspects of human society – including, but not limited to, conflict, crime and violence – are rapidly evolving.

More significantly Kilcullen also offers a theory of “competitive control” that shows how non-state armed groups, drug cartels, street gangs and warlords – draw their strength from local populations; and then providing useful ideas for dealing with these groups and with diffuse social conflicts in general.

But for many of the struggles ‘we’ will face, Kilcullen concludes, ‘we’ will require multi-disciplinary approaches and a combination of local and international experts collaborating. Which sounds like a tremendous launch pad for a company that provides just that service…

I must admit that getting through this book was hard work for me. I’m not sure if it was too abstract, whether the connection to define broad trends between examples is stretched too far, whether it was a bit repetitive in making the argument, or whether it was just a little leading or biased. At times it read a bit like an academic thesis and at others like a Caerus prospectus. “What I’ve described isn’t theory. It’s what our teams do all over the world, in conflicts and crises in half a dozen different cities”, he states…almost breathlessly…And confusingly, he completes the book with a 30 page appendix titled “on War in the Urban, Networked Littoral’ that seems to be a military summary of the book; not sure what the editor was thinking here.

Kilcullen skirts across the potential for purely conventional state versus state conflict and envisages that all wars in the future will inevitably have a messy irregular dimension. Kilcullen also largely ignores another mega trend that has driven wars and conflict in the past – the competition for resources. And human societies are tremendously adaptive; so as these destabilising pressures on society build there is also tremendous opportunity for innovation to prevent a descent into global chaos, violence and anarchy.

No doubt, wars in the future will have evolving characteristics and pose different threats and opportunities. Having made his reputation advising on war in the mountains of Afghanistan, the next market opportunity seems to be in the megacities and mega-slums of the world. As a former ‘COINdinista’ Kilcullen has now placed his bet on irregular war as the way of the future.

Out of the Mountains certainly explores the potential future character of war and conflict; the democratisation and globalisation of the use of violence. But war will continue to follow age-old truths; that is: it is political; it is human; and it is uncertain because it is political and human.

Out of the Mountains provides yet more conceptual food for thought for capability developers in the Australian Defence Force and other Australian Government national security agencies. As the ADF’s amphibious capability is developed in the coming years it would certainly be useful to start thinking hard about what an embarked force might have to do once it gets off the ship and in what operating environment. Out of the Mountains offers a good place to start that process as far as the potential operating environment is concerned.

Contact Marcus Fielding about this article.