Gustav Adolph (Gus) Ebeling was born at Percydale in the Pyrenees Ranges of the central Victorian goldfields on 5 March 1871.

Retrieved 30 April 2020, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91383842

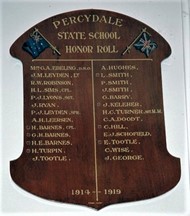

Percydale is now a ghost town but once boasted two butchers, two hotels, a blacksmith, a dress shop, three banks, two grocers and a Chinese shop. Additionally, there were two churches, a post office, a police station and a Temperance Hall. The school had 113 registered pupils with an average attendance of 40.[1] The Ebeling family had two separate parcels of land at No. 2 Creek, Percydale, which is around 11 kilometres west of the small township of Avoca.[2]

Gus’s father, Claus Ebeling, came to the Victorian goldfields in 1854 from Celle, Hanover, in Germany. A farmer in Germany, he joined the tens of thousands who made their way to Victoria to chance their arm at gold mining. Claus became a naturalised British subject in 1872 whilst still working as a miner and living at Majorca, along with four other compatriots who were members of the German Association of McCallums Creek.[3] Gus Ebeling’s mother, Auguste Lohse, was also German, having been born in Ahrensburg, which is a town in the district of Stormarn, Schleswig-Holstein, northeast of Hamburg. She migrated to Australia in 1858, aged 23.[4]

Her older brother, Wilhelm, a 25-year-old baker, had preceded her to Melbourne in October 1857. Wilhelm later held adjoining land to the Ebelings in Percydale. However, the two German brothers-in-law don’t seem to have got on too well over the years. As early as 1870, Wilhelm had taken Claus to Court over monies owed to him.[5] In 1888, Wilhelm again brought a damages claim against Claus due to Ebeling’s horses trampling his pea crop.[6] And, in 1893 during the short-lived Iron Bark Gully gold rush just west of Avoca[7], the two men were again in dispute, this time over their respective mining claims with Lohse lodging a trespass claim against the Ebelings, which included Gus and his brother. The claim was ultimately dismissed.[8]

Claus and Auguste married in 1860 and had six children. Gus (Gustav Adolph) was the fourth born of four girls and two boys.[9] Gus seems to have been a bright boy at school and was even successful in being invited to sit the examination to enter the Victorian Public Service but chose to remain on the land.[10] Gus Ebeling was energetic but seemed to periodically attract or become embroiled in silly controversies. At the age of 20, he was involved in an alleged ‘roll stuffing’ scandal at Avoca in 1892, along with some underage voters, much to the chagrin of the local member who was quite unpopular in Avoca.[11]

The military also proved attractive and he served with distinction in the first contingent of the 5th Victorian Mounted Rifles in the Boer War from November 1899 to December 1900. He started as a private and ended up as a commissioned officer with the rank of Lieutenant.[12] [13] During that period, he wrote a remarkable series of 32 letters back home about his experiences that were published in the Avoca Mail and other newspapers.[14] On his return to Avoca in early January 1901, he was welcomed at the railway station by shire councillors, a brass band, members of the mounted rifles, the fire brigade and 300 locals who escorted him through town to a reception at an overflowing shire hall that ‘was marked by much enthusiasm’ and ‘deafening cheers’ when Ebeling responded to a toast in his honour.[15] [16]

Such was Ebeling’s passion for the military that by late January he had re-enlisted to return to South Africa, this time with the controversial second contingent of 5th Victorian Mounted Rifles which departed in February 1901 and returned in March 1902.[17] At a dinner held in the officers’ mess at the Langwarrin military camp on the night before disembarkation, Ebeling was presented with a gold watch on behalf of the people of Avoca and a ‘handsomely illuminated address’ from the Avoca Mail in thanks for the letters he wrote whilst in South Africa. The watch bore the following inscription: Presented to Lieut. Gus Ebeling by residents of Avoca and district in recognition of fifteen months’ active service in the Transvaal War, October 1898 to January 1901.[18] Ebeling stayed on after the Boer surrender and in May 1902 the longest-serving Victorian in South Africa was appointed to a new role in army transport setting out on an expedition from Bulawayo with the object of laying a railway across Africa.[19] [20] However, it is uncertain how long he remained in South Africa and he probably returned to Australia in September 1902.[21] In July 1904, Ebeling was awarded the King’s Medal with two clasps [22] for his Boer War service and in September 1904 he attended the first reunion of the 5th Victorian Mounted Rifles held in Melbourne in September 1904.[23]

Leader, 16 February 1901, (The Leader Supplement), p. 3.

Retrieved 2 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article198086696

In 1906, the 35-year-old Gus married a local girl, Emily Constance Sweet, aged 29, who was from a large family of nine children at a gala wedding with the service conducted at St. John’s Anglican Church in Avoca.[24] Immediately after the wedding, they moved to Adelaide where Ebeling sold agricultural equipment but this didn’t seem to have worked out and they returned to Avoca a couple of years later when his father died.[25] Gus and Emily did not have any children and Emily died in 1932, aged 54.[26] Just before the First World War, the innovative Ebeling became well known across the district for developing a hardy and higher-yielding strain of ‘Avoca wheat’, which appears to have been widely adopted across the region.[27] After the First World War, he even became involved in propagating and disseminating a strain of ‘Gallipoli’ oats that he obtained from local farmers when convalescing on Imbros island in Greece.[28]

First World War

Within a month of the break out of World War One, Gus Ebeling had enlisted in the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF). By 26 August 1914, the forty-three-year-old military enthusiast had joined over 40 younger volunteers from the Avoca – Maryborough district at the Broadmeadows military camp, some 16 kilometres from central Melbourne. The camp was established on 19 August 1914, two weeks and one day after the announcement of war, when 2,500 men set off for Broadmeadows from the city. Crowds had lined the streets as these men in mufti, some clutching Gladstone bags and some carrying neat parcels, walked from Victoria Barracks in St Kilda Road to the camp.[29]

The district’s total of 45 was regarded as a ‘fine contribution’. A Maryborough bank manager, Boer war veteran and Citizens Military Forces Captain, Charles Henry Raitt,[30] had seen the second detachment of 20 men to their train on 25 August and they went off amid the hearty cheers of a large crowd that had assembled accompanied by the West State School boys’ bugle band. As was the case with the first batch in the previous week, the schoolboys paraded to the station along the principal streets, and ‘all marched very creditably’. Writing to a friend at Avoca, Gus Ebeling said:

We got down to town all right and are quite settled in camp. They are a splendid lot of men; the Avoca and Maryborough men who travelled together were the best-behaved lot of young soldiers that I have had anything to do with, and I feel sure they will do credit to their respective districts. They are all well and happy, although they have had a very rough time.[31]

According to the Embarkation Rolls of October 1914, most of the men who enlisted from the Avoca district served in the same unit in line with the deliberate policy of keeping locals together. Gus Ebeling, Matthew Rafferty, Arthur Summerfield, William French, Dave Summers and Reg Johnson were all in the 8th Infantry Battalion, ‘F’ Company.[32] Ebeling was the officer-in-charge of the company. The 8th Battalion was recruited from rural Victoria within the first two weeks of war being declared. The 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th Battalions were recruited from Victoria and formed the 2nd Brigade of the First Australian Imperial Force.[33]

Although it is not possible to put names to faces, the Embarkation Roll for the 8th lists all the members of the company at the time of departure from Melbourne. The three officers likely are Lieutenant Gus Ebeling, aged 43, a farmer and grazier from Avoca, Victoria, and a veteran of the Boer War (centre) and Lieutenant William Thomas Yates, aged 29, Dairyman of Newminster Park, Camperdown, Victoria, and 2nd Lieutenant Maurice Leslie McLeod, aged 20, a tailor of 405 Gregory Street, Ballarat, Victoria, on either side of him.

Retrieved 30 March 2017, Australian War Memorial, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/DAX2563/.

Gus Ebeling, along with his comrades in arms in the 2nd Brigade, took part in the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, as part of the second wave. It was during the landing that he was first mentioned in despatches by Brigadier General William Kinsey Bolton who commanded the 8th Battalion early on in the First World War, including during the landing and opening battle at the Dardanelles.[34] In the chaos of the initial landing, word had passed along a portion of the line on the left adjoining the 8th Battalion that the troops should retreat from battle. Owing to units becoming mixed with numerous officers, NCOs and casualties, a number of the troops started to withdraw. However, the mature-aged Ebeling and fellow Captain, J.E. Sergeant (who was later killed in action on the same day[35]) rallied the troops and ‘by their personal endeavours stopped the retirement and led the men into position again’.[36] It was also during the landings that Ebeling was wounded in the head and foot as the result of a bursting shell.[37] He later returned to duty at ANZAC on 5 May 1915 where he was again mentioned for gallantry in action and presumably took part in the Second Battle of Krithia from on 8 May 1915. A few weeks later, he was promoted to Major and on 26 August 1915, he was awarded a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his efforts at the first landing and the intervening months.

As with so many others at Gallipoli, he became very ill over the summer, developing diarrhoea and dysentery and was hospitalised at Lemnos in late September 1915. In a letter penned in October 1915 that was later published in the Avoca press, Ebeling wrote that on evacuating Gallipoli, ‘We came out of the trenches…very sick and wasted, and had gone into hospital.’[38] In another letter from England in November 1915, he stated that:

I had to throw in the towel. I am feeling pretty well, though I can’t put on any weight since I came to England. I gained 12 lbs in a fortnight on the hospital ship, but have since stood still since, though I have been living on the fat of the land and plenty of Devonshire cream…I am expecting my wife in London in eleven days and will be pleased when she arrives. Am worrying a lot over her safety as the submarines are very active in the Mediterranean…I am trying to get permission to go to France. Now that I am getting better, I want to get to the front again – a sort of grand socialism of comradeship seems to be pulling at one all the time. I would dearly love to have stuck to it all through. I was the only officer in our battalion who stuck to it for five months without a spell and had much luck right through. During that time – with the exception of four hours, when we gave the enemy an armistice to bury their dead – we were under fire for every minute, and if at any time firing ceased for two seconds, everyone would wake up. Captain Yates is with me.[39] He is the only original officer of my company who is left. This war has made a lot of people poor, and those socialists who are always wanting to down the aristocracy should be thankful that we have them.[40]

Due to the ongoing nature of his illness, which included the skin condition, sycosis menti, he did not see active service again, convalescing in both Malta and London before returning to Australia in early 1916. In March 1916, he unobtrusively slipped back into Avoca, apparently eschewing any publicity. Although he had kept his return secret, word soon got out and ‘he was besieged by numerous friends who were anxious to renew association with a man who had brought so much honour to the town.’[41]

The local soldiers’ committee had intended to make arrangements for a reception for the Major but he declined. Gus spoke appreciatively of ‘the Avoca boys out yonder’ and the bond of good fellowship existing between himself and his men, paying tribute to the magnificent heroism of the Australians. However, he refrained from taking any credit upon himself, merely stating that he was only doing his duty. According to the local paper, Major Ebeling was ‘not egotistical and is more to be admired for that reason.’[42]

After further convalescence, he assumed the private treatment of his condition in April. He returned to duty in June 1916 as commandant of the Bendigo Military Camp after it was decided to move it from the racecourse at Epsom, Bendigo to the adjacent golf course after a meningitis outbreak. [43] [44] [45] [46] The ‘6 foot’ Ebeling was described as a ‘capable, thorough and humane officer, who had risen from the ranks, saw a good deal of active service, and although a strict disciplinarian, was considerate to the officers and men under him.’ He was ‘a tall heavily built, powerful man, quiet unassuming, middle-aged and determined.’ His ‘youthful appearance belied his age, he could be relied upon and was a soldiers’ officer.’[47]

Ebeling soon made a mark on the camp which appeared to suffer from some laxness in discipline and had experienced several thefts of military property. However, his ‘Prussian’ methods attracted controversy and by August there were complaints regarding the heavy penalties inflicted for breaches of discipline.[48] The Bendigo East Political Labor League passed a resolution requesting information on the fines and penalties inflicted on soldiers in the Camp since Ebeling’s appointment be provided to the Commonwealth Parliament.[49]

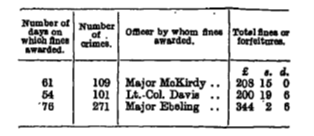

On 22 September 1916, former acting prime minister Senator George Pearce responded to a request concerning the imposition of fines and penalties since the appointment of Ebeling in comparison to the previous commandants:

The increase in the number of cases dealt with by Ebeling was attributed to him being in charge during a period in which a large number of men had missed embarkation (desertion) and penalties inflicted covered the offences of avoiding embarkation and subsequent offences by these men.[50]

In early October 1916, Ebeling was transferred to the headquarters staff at the Royal Park Military Camp in Melbourne.[51] He was also to serve as the Chairman of the District Standing Board, Victoria Barracks on an annual salary of 425 pounds per annum.[52] Late in 1916, Ebeling put his Avoca properties on the market, which included six paddocks, presumably as he was now based in Melbourne and living in South Yarra.[53] [54] However, it seems that the properties were not sold as he was still selling his stock at the Avoca sales in August 1917.[55]

In October 1918, he left military service to go into a property partnership with by then-Senator William Kinsey Bolton and Francis Oddie to lease and, in Ebeling’s case, also manage the historic Eurambean East Estate at Beaufort.[56] The arrangement only lasted about six months with Ebeling returning to farming at Avoca. There was also a dispute over money owing. [57] [58] [59] Ebeling maintained his military commission during the 1920s and was not formally transferred to the retired list until May 1931 after he had turned sixty and perhaps because of his connection to the events of March 1931.[60]

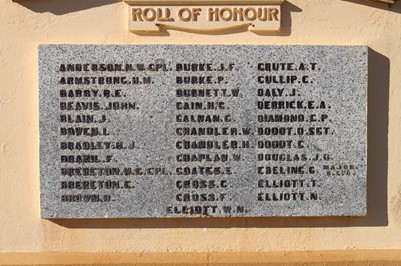

RSL Memorial Hall, Avoca, Victoria

Retrieved 3 May 2020, http://monumentaustralia.org.au/australian_monument/display/102323

The Follies of March

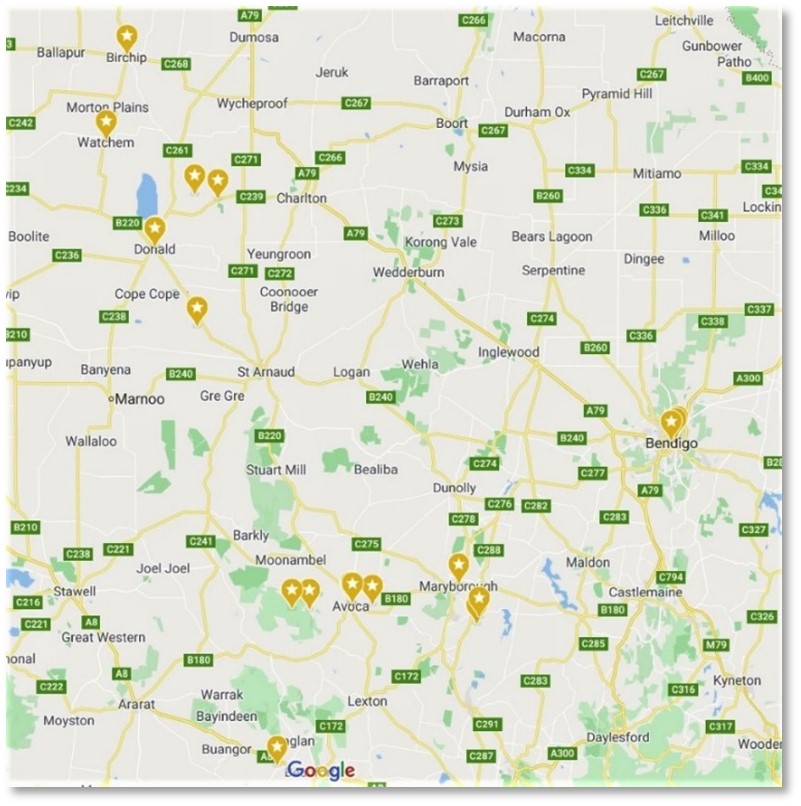

In early March 1931, Gus Ebeling was very agitated along with many other ex-servicemen. They believed a communist revolution was afoot that oddly Catholics had also gathered to the fray along with the unemployed and were about to seize the key townships of the Wimmera and Mallee in Victoria’s north-west. A communist Red Army was expected to sweep northwards onto the Murray River border town of Mildura from Bendigo, Maryborough and Ballarat. In small towns along the way, it was anticipated that local Catholics would rise as a Fifth Column in support of the Reds.

Retrieved 8 May 2020, https://www.google.com.au/maps/@-37.003912,143.2540139,9.69z?hl=en

It was during the dark days of the Great Depression and the sixty-year-old Ebeling had been busy. At midnight on 3 March 1931, he arrived by car at the small Wimmera town of Donald, having driven from Avoca some 100 kilometres to the south-east. In tow were fellow Great War veterans, Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Vivian Deeble[61] and Major James Sproat, the soon-to-be second in command of the local branch of the League of National Safety (LNS) aka the ‘White Army’.

Deeble was a schoolteacher and the principal of Essendon High School in Melbourne before the War but had turned his hand to farming after his homecoming and had properties at Marnoo and Gowar East in the Wimmera during the 1920s. By1931, he was the manager of Banenyong Estate, which was owned by Sproat’s brother William. During World War One, Sproat and Deeble had served together in the 8th Light Horse Regiment. Deeble had commanded the Regiment for brief periods with Sproat as his quartermaster. Deeble had also led the second wave of the infamous charge on the Nek at Gallipoli on 7 August 1915 but hadn’t gone over the top as the commander of the 8th, Lieutenant-Colonel A. H. White, did in the first wave.[62]

At the end of October 1917, Sproat was wounded by a shell during the Battle of Beersheba in Ottoman-ruled Palestine.[63] Deeble’s war ended in mid-1918 when, after a series of illnesses that included pleurisy and enteric, his commission was terminated and he returned to Australia. Likewise, Sproat was discharged in late 1918 after being found to be suffering from neurasthenia after Beersheba, which was a common diagnosis during World War I for ‘shell shock’.[64] Sproat had been a station hand at his brother’s farm before enlisting in September 1914 but became a soldier-farmer at Ultima, near Swan Hill, about 120 kilometres from Donald, after the War.[65]

Ebeling must have picked them both up at Banyenong Estate and on arriving in Donald, they roused a local solicitor, Cecil Harwood Davies, another Great War veteran.[66] Ebeling broke the incredulous news that a communist revolution had already broken out in Melbourne and was heading their way. This was Ebeling’s second visit to Donald in three days, having previously met with Deeble, Sproat and Lieutenant-Colonel Ernest Albert Harris[67], another farmer from Jeffcott a few kilometres out of town, on Sunday, 1 March 1931. On his first visit, he warned that the revolution would happen the following Friday, 6 March 1931, the day that huge unemployment marches were planned across Australia.

Ebeling so convinced Harris and Sproat of the impending disaster that they formed a local branch of the LNS and began swearing in all reputable citizens, bar the Catholics. The swearing-in was undertaken by local Justice of the Peace, W.G. ‘Jack’ Pitty, a land and stock auctioneer and Real Estate Agent.[68] Pitty was ‘a nervous excitable man’ who it was said ‘quite lost his head over the affair’.[69]

The local copper – a policeman of twenty-three years standing – Senior Constable John McDougall, a Catholic, knew Ebeling from when he was stationed at Avoca between 1910 and 1913.[70] He didn’t like him, and they had had a falling out when he was there. He thought that Ebeling was ‘hot-headed’ and a ‘human storm centre’. When he arrived in Donald spreading hysteria about a Red/Catholic uprising, McDougall had warned Ebeling ‘to be careful about what he said and did’. Unfortunately, Ebeling ignored McDougall’s sound words of advice.

It is also known that Ebeling alerted other ex-military officers in Birchip, St Arnaud and Ouyen, and possibly he visited other Wimmera and Mallee communities as well.[71] These meetings caused panic and often absurd actions being undertaken.[72] Some of the rumours which were current in Donald after Ebeling’s departure were that:

A ‘red army’ was supposed to be marching on Bendigo, Ballarat, and Geelong and the reds were very strong in Bendigo which was likely ‘to fall immediately’. Another ‘red army’ was to march on Mildura, taking in Wedderburn, Wycheproof and Donald, en route.[73]

On Sunday – the day of Ebeling’s first visit to Donald – resident priest, Father John Francis Coughlin, had celebrated his customary early morning Mass. He was later accused of preaching an anti-Protestant sermon at the Mass, apparently advising Catholics not to do business with non-Catholics. However, sermons were never given at the early Mass. During the week, local children began to taunt their Catholic schoolmates with threats about what their fathers were going to do when the revolution started. On the evening of 3 March 1931, a meeting of the Hibernian Society[74] at Donald’s Central Hall was surrounded by a few non-Catholics who closely scrutinised attendees. One loudmouth opined that ‘they [the Catholics] were slipping into the meeting very quietly that night’.

Throughout the week, Catholics were watched. Men grouped at street corners would stop talking when a local Catholic approached and eyed him or her suspiciously as they passed. Businesses were boycotted, including the Hotel Donald, whose licensee, Grace Fitzgerald, was a Catholic. Events started to reach a fever pitch on Thursday, 5 March 1931 when, for the first time in its history, a meeting of the Masonic Lodge was guarded by Masons positioned outside the hall. Father Thomas Hussey from Watchem, some 35 kilometres away, had visited the bank manager of the Donald branch of the Bank of Victoria on business that day. When he returned home, he found two men on his veranda who wanted to search his car because they believed he had firearms on board. The furious Hussey complained to Coughlin and both priests reported the incident to their local Bishop and Archbishop Daniel Mannix[75] in Melbourne.

Also, on 5 March, the well regarded and highly decorated Lieutenant-Colonel Bernard Duggan, DSO and Bar,[76] a soldier-farmer from Swanwater 25 kilometres south of Donald, was contacted by Wallace Arthur McIlroy. Duggan was a Catholic and McIlroy, now a rabbit inspector had been a private in the 8th Light Horse Regiment and was thus another compatriot of Deeble and Sproat. McIlroy had been gravely wounded in the left arm at the Battle of the Nek. He also developed serious influenza and eventually returned to Australia in August 1916 and was discharged on medical grounds two months later.[77]

Duggan, who served in the 21st Battalion throughout the entire war, would have also known Ernest Harris as they served together when the unit was formed at Broadmeadows in 1914 with Harris as second in command and Duggan as a company commander. They later served together at Gallipoli before Harris was transferred to the 59th Battalion in March 1916 on returning to Egypt after Gallipoli was evacuated.

McIlroy was from the nearby township of St Arnaud and asked Duggan to come to town and meet him. When asked why McIlroy said that he had it on ‘good authority’ that both the St. Arnaud and Donald convents were being stocked with service rifles. Duggan dismissed this as nonsense and mockingly asked him where McIlroy had got such an absurd story. Duggan went on to say that ‘the sisters would be frightened to death if anyone fired a pea rifle, let alone service rifles’. After being put in his box, McIlroy became abusive. Duggan also passed this information onto Father Coughlin, as he had previously been one of his parishioners.

The Irish-born Father Coughlin and a local Catholic doctor, William Joseph Flanagan, were themselves accused of bringing arms and ammunition by car into the district via their various journeys to Melbourne and other places. Flanagan was further accused of transporting communists into the region because he had given a lift to a couple of ‘swaggies’. Also, Harry Kelly, a Donald dentist, was said to have concealed bombs in his car when in fact he had purchased two cases of tomatoes when in St. Arnaud.

Such a mania began to impact on people’s health. The Mother Superior, who was alleged to have secreted arms and ammunition in her convent, became quite ill, along with several other Catholics. The ‘timid and shy’ Father Coughlin was so shaken up by the whole affair that after it was all over he obtained a transfer to Horsham, even though the well-respected priest had served in Donald for nine years and overseen the building of the Catholic school.[79]

Nevertheless, local Catholics weren’t prepared to take the accusations lying down. Hotelier Grace Fitzgerald approached Catholic solicitor Cyril Robinson about taking action against the culprits but he advised her to hold off. Dr Flanagan and Robinson then went to Father Coughlin to discuss the possibility of prosecuting those responsible. The priest first approached his Anglican counterpart, Reverend Edmund Henry Hoffman,[80] and on getting his support went to see Major Sproat, warning him that if any damage was done to Catholic property that he, along with his three other cohorts – Pitty, Harris and Deeble – would be held personally responsible. Coughlin also approached Senior Constable McDougall who said that he would report the matter to the ‘authorities’ but told him that he could not take any action unless rioting or other disturbances of the peace occurred.

After Coughlin’s call to Sproat, he was visited by Cecil Davies and Pitty who assured the padre that no offence was intended in not permitting Catholics to join the LNS, but Catholics were barred because the Church would not allow its flock to become members of a secret organisation. Coughlin was highly scathing of ‘that secret society’. He also pointed out the serious consequences of undertaking embargoes and boycotts in a small town. Davies agreed that their supporters had gotten ‘quite out of hand’ and that he had tried to quell the wild rumours. However, Pitty became aggressive when Coughlin reiterated his threat of drastic action against anyone damaging Catholic property. According to most people, the excitable Pitty was also a fool. Reflecting afterwards, Davies strongly regretted the ill-feeling that was caused by the episode. He had nearly come to a lawsuit over it, the Golf Club had split in two and the Catholic owners of the racecourse had refused to allow the Golf Club the use of the course for their two longest holes as a consequence. It had also affected his business and while he had previously thought better of Ebeling and the LNS he didn’t anymore.

Fortunately, there were some voices of reason, as both the town’s lawyers and Reverend Hoffman were responsible for pouring oil on the troubled waters in Donald in early March 1931. Father Coughlin later stated that had a sincere regard for all the other gentlemen involved in the unhappy affair, except for Ebeling and Pitty, who were the direct cause of all the ill-feeling. He hoped that some action could be taken against them for their roles in stirring up local feelings.[81]

Pretender and “a real Fritzy’?

In his book on the events of March 1931, historian Michael Cathcart thought that Gus Ebeling may have been involved in military intelligence, hence his link to the White Army. Cathcart visited Avoca when researching his book, ‘Defending the National Tuckshop: Australia’s Secret Army of Intrigue of 1931’, in the late 1980s. At the time of Cathcart’s visit, it seems some of the older townsfolk he talked to weren’t too keen on Ebeling even though he had died over 40 years earlier in 1943. ‘Ebeling was a real German,’ one said. ‘He’d go and kick a calf that was lying down – kick it again and again rather than tell it to get up. He was that sort of a bloke.’ Another resident agreed. ‘Major Gus was really a Fritzy, a squarehead, you know what I mean. He wasn’t very popular in the town – he was sort of a little dictator’. Perhaps curiously, there also seemed to be little love lost between Victorian Police Commissioner Thomas Blamey who was considered the head of the White Army[82] and his apparent leading man in the Wimmera-Mallee, Gus Ebeling. According to one of the Avoca locals, ‘Ebeling didn’t like Blamey. Hated him. He said that on Gallipoli Blamey used to make him walk along the spur nearest the Turks so that he’d get shot’.[83]

There had been a considerable build-up to the much-heralded ‘Unemployed Day’ on 6 March 1931 and there were expectations that violence would occur, largely as a result of claims by militants that there would be disturbances in the streets in support of their demands. Consequently, big crowds gathered on the footpaths to watch the various marches, if not participate in them. The Melbourne march ended up being quite a fizzer, as only several thousand turned up and there was a heavy police presence. Most of the time seems to have been taken up in discussions between a deputation of Trades Hall leaders and the Chief Secretary, Tom Tunnecliffe, who strongly urged the unemployed that violence was not the answer. In Geelong, only two hundred marched and a large crowd who had come to witness the parade were disappointed, presumably by a lack of confrontation.[84] And, as Cathcart had to acknowledge about 6 March 1931: ‘Of course, nothing happened – there was no uprising, there wasn’t a revolution, the nuns did not hand out .303s to the rebels outside’.[85]

Cathcart also questioned the nature of Ebeling’s DSO, speculating that because he was unable to locate documents relating to the details of the award that this was perhaps an indication that Ebeling had been connected with intelligence. However, Ebeling’s war service file is quite clear that he was awarded the DSO for actions at ANZAC both over the first days at the landing and through to the period in August 1915 when he received the decoration.

Cathcart further speculated that because Gus Ebeling’s Will had been drawn up by Sir Edmund Herring’s law firm and, as Sir Edmund was a ‘district commander of the White Army for the Mornington Peninsula’, then ‘if Ebeling did have a connection with the White Army leadership, this was probably it.’[86] However, the facts are that Gus’s father, Claus Ebeling, had his Will drawn up Sir Edmund’s father in 1901 – he too was a lawyer from nearby Maryborough – also with the name Edmund.[87] Indeed, Edmund Herring, senior, represented Claus Ebeling in many legal matters over the years.[88] In other words, the Herrings were lawyers for two generations of the Ebeling family and this relationship predated the events surrounding March 1931 by around 38 years. Ultimately, Cathcart had to concede that his endeavours to link Ebeling to military intelligence and with the top brass of the White Army produced a ‘less than conclusive result.’[89]

Apart from his involvement in the bizarre events of 6 March 1931, Ebeling later fell foul of Major General Charles Henry Brand due to his assertions that he had received two Bars to his DSO. Brand, who was the first Australian to receive a DSO at Gallipoli, knew Ebeling having served with him in both the Boer and Great Wars.[90] Ebeling’s false claim so incensed Brand that in 1939 he wrote to the military authorities seeking clarification of his war medals, stating that Ebeling had been ‘masquerading as a 2 (two) bar DSO man.’ Brand was aware that Ebeling got his DSO at Gallipoli but he had returned to Australia after the evacuation and so could ‘not possibly have 1 bar, let alone 2 bars to his DSO.’ Brand concluded that ‘he was a good officer and I and don’t like to hear of him doing [such] a stupid thing.’ In reply, the military authorities confirmed that Ebeling did not receive any Bars to his DSO. [91]

Ebeling also seems to have misrepresented his rank and Brand’s intervention to set the record straight was unsuccessful. Later in life, the eccentric Ebeling was said to have driven around Avoca in an old Chevrolet Coupe and even tried to enlist for the Second World War but ‘the recruiting people thought he was too old’ at the age of seventy.[92] However, in Ebeling’s 1943 death notices, two former comrades, one from the 8th Battalion, were still of the mistaken belief that he had one Bar to his DSO and that his rank was Lieutenant-Colonel when in fact his highest rank was Major. Unfortunately, an ageing Gus Ebeling exaggerated his military achievements and became entangled in unnecessary controversies. From a man who was once honoured as a military hero through the streets of Avoca and hailed for his hybrid ‘Avoca wheat’ to a man who was remembered by some locals as an unpopular little dictator – a most ambivalent and intriguing legacy.[93]

Retrieved 3 May 2020, http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/conflict/multiple/display/30101-avoca-soldiers-memorial

Note that Gus Ebeling’s rank is recorded correctly as Major with a DSO (no Bar)

Written by Peter Vodicka 2020

Bibliography

Primary

Official Sources

Commonwealth – Publications, Archives and Manuscripts

Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. 2019. http://adb.anu.edu.au/.

Australian War Memorial. 2019. https://www.awm.gov.au/.

Cecil Harwood Locke Davies. 1918. Australian War Memorial. 20 December 2019. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/R1604835.

Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, 27 January 1916 and London Gazette, 5 November 1915.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission. https://www.cwgc.org/find/find-war-dead/results/?cemetery=SHELL+GREEN+CEMETERY&casualtypagenumber=16.

Hansard, Senate, No. 38, 1916, Friday, 22 September 1916.

Murray, Pembroke Lathrop. and Australia. Department of Defence. Official records of the Australian military contingents to the war in South Africa/compiled and edited for the Department of Defence, A.J. Mullett, Govt. Printer Melbourne 1911, pp. 214-225 and pp. 279-281. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015070381432&view=1up&seq=4.

National Archives of Australia. 1918. B2455, SPROAT JAMES.

—— B2455, Deeble A V. 1914 – 1920.

—— Ebeling, Claus – Naturalisation, Series number A712, Control symbol 1872/A13193.

—— B2455, Ebeling, G.

—— B2455, McIlroy W A. 1918.

—— B2455, SERGEANT, John Edwin

—— White Army A395, NN. 1931.

Victoria – Publications Archives and Manuscripts

Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 7591/P0002 unit 419, item 106/509, Claus Ebeling. Date of grant: 01 May 1908; Date of death: 26 Oct 1907; Occupation: Farmer; Residence: Avoca, http://access.prov.vic.gov.au/public/component/daPublicBaseContainer?component=daViewItem&entityId=5138985631

Select Committee Upon Alleged Roll Stuffing at Avoca, Andrews, C., Bowman, R., Craven, A. W., Dixon, E. J., Herring, M., & Murphy, E. (1893). Report from the Select Committee Upon Alleged Roll Stuffing at Avoca: Together with the proceedings of the Committee and minutes of evidence. Melbourne: Robt. S. Brain, Government Printer, https://pov.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_GB/parl_paper/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fSD_ILS$002f0$002fSD_ILS:24880/one?qu=Report+from+the+Select+Committee+Upon+Alleged+Roll+Stuffing+at+Avoca%3A+Together+with+the+proceedings+of+the+Committee+and+minutes+of+evidence&te=E_PAR_PAPER.

Tout-Smith, D. (2003) Hibernian Australian Catholic Benefit Society, Museum Victoria Collections, http://collections.museumvictoria.com.au/articles/2036,

“Victoria’s Contribution to WW1: Sharing Victoria’s Stories and Making Contributions.” 2014 – 2018. ANZAC Centenary. 29 March 2017. http://anzaccentenary.vic.gov.au/history/victorias-contribution-wwi/.

Victoria Police Gazette. Melbourne: Victorian Government, 13 January 1910.

Victorian Government Gazette. Melbourne: Victorian Government, 10 June 1931.

Newspapers

Advocate

Age

Argus

Australasian

Avoca Free Press and Farmers’ and Miners’ Journal

Avoca Mail

Ballarat Courier

Ballarat Star

Bendigo Advertiser

Bendigo Independent

Bendigonian

Maffra Spectator

Maryborough and Dunolly Advertiser.

Punch

Register

St Arnaud Mercury

Tasmanian News

Western Mail

Secondary

Books and Manuscripts

Bean, C.E.W. The Story of Anzac: From 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation. 1941. Cited in http://alh-research.tripod.com/Light_Horse/index.blog/1919271/the-nek-beans-account/#.

Cathcart, Michael. Defending the National Tuckshop: Australia’s Secret Army of Intrigue of 1931. Melbourne: McPhee Gribble Publishers, 1988.

—— “The White Army of 1931: Origins and Legitimations.” June 1985. Australian National University. Unpublished Master of Arts Thesis. 19 December 2019. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/113889.

“Ebeling Cash Store.” 13 May 2016 and 5 November 2018. Avoca & District Historical Society. 2019. https://www.facebook.com/717061235023833/photos/can-anybody-tell-us-where-in-high-street-avoca-the-ebeling-cash-store-was-situat/1099547930108493/ and https://www.facebook.com/717061235023833/photos/a.717874164942540/1099547930108493/?type=3&comment_id=2065710656825544.

“Major A. V. Deeble.” 2017. Empire Call. 18 November 2017. http://empirecall.pbworks.com/w/page/27047096/Deeble-A-V-Major.

Broadcasts and Other Internet Sources

Ancestry.com. Australia. Electoral Rolls, 1903-1980 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., Original data: Australian Electoral Commission. [Electoral roll]. 2010.

Cathcart, Michael. Carr talks about the return of POWs from Japan. with Margaret O’Neill. Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Lateline. 2 September 2003. Radio. http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/content/2003/s937662.htm.

Google Maps. https://www.google.com.au/maps/@-37.003912,143.2540139,9z?hl=en.

Lohse, Auguste Henrietta Wilhelmina. MyHeritage Family Tree, https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-1-130525801-15-11/augusta-henrietta-wilhemina-hetta-wilhelmina-lohse-in-myheritage-family-trees.

Lohse, Auguste. Staatsarchiv Hamburg; Hamburg, Deutschland; Hamburger Passagierlisten; Microfilm No.: K_1706 Hamburg Passenger Lists, 1850-1934 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com.

Monument Australia. http://monumentaustralia.org.au/.

Wardlaw, Louis. ‘Percydale’s Heritage’, Gold Net Australia Online Magazine, August 1999, http://www.gold-net.com.au/archivemagazines/aug99/28024554.html#12. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

Young, Anne. “First volunteers in Broadmeadows camp.” 2014. Avoca during World War 1. 30 March 2017. http://avocaww1.blogspot.com/2014/08/first-volunteers-in-broadmeadows-camp.html.

[1] Louis Wardlaw, ‘Percydale’s Heritage’, Gold Net Australia Online Magazine, August 1999, http://www.gold-net.com.au/archivemagazines/aug99/28024554.html#12 accessed 1 April 2017.

[2] ‘Avoca Warden’s Court’, Avoca Mail, 2 November 1886, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202500500, accessed 1 April 2017.

[3] Leunig, Carl Heinrich Julius; Ebeling, Claus; Lange, Christoph Friedrich Louis; Lange, Christoph Ludwig August; Veit, Adam Christian – Naturalisation, National Archives of Australia, Series number A712, Control symbol 1872/A13193, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=1581449, accessed 2 April 2017.

[4] Auguste Lohse, Staatsarchiv Hamburg; Hamburg, Deutschland; Hamburger Passagierlisten; Microfilm No.: K_1706 Hamburg Passenger Lists, 1850-1934 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com, accessed 1 April 2017.

[5] Avoca Mail, 15 October 1870, p. 2 and Victoria Government Gazette, 8 June 1888, p. 1681.

[6] Avoca Mail, 30 October 1888, p.2.

[7] ‘The Rush at Ironbark Gully, Avoca District’, The Australasian (Melbourne, Vic.: 1864 – 1946), 16 September 1893, p. 30. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article138659831, viewed 19 Dec 2019.

[8] Avoca Mail, 1 August 1893, p. 2.

[9] Auguste Henrietta Wilhemina Lohse, MyHeritage Family Tree, https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-1-130525801-15-11/augusta-henrietta-wilhemina-hetta-wilhelmina-lohse-in-myheritage-family-trees, accessed 1 April 2017).

[10] Avoca Mail, 27 May 1881, p. 2.

[11] Victoria. Select Committee Upon Alleged Roll Stuffing at Avoca, Andrews, C., Bowman, R., Craven, A. W., Dixon, E. J., Herring, M., & Murphy, E. (1893). Report from the Select Committee Upon Alleged Roll Stuffing at Avoca: Together with the proceedings of the Committee and minutes of evidence. Melbourne: Robt. S. Brain, Government Printer, https://pov.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_GB/parl_paper/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fSD_ILS$002f0$002fSD_ILS:24880/one?qu=Report+from+the+Select+Committee+Upon+Alleged+Roll+Stuffing+at+Avoca%3A+Together+with+the+proceedings+of+the+Committee+and+minutes+of+evidence&te=E_PAR_PAPER, accessed 24 December 2019.

[12] Avoca Mail, 17 October 1899, p. 2 and Victoria Government Gazette, No. 23, 8 February 1901.

[13] Murray, Pembroke Lathrop. and Australia. Department of Defence. Official records of the Australian military contingents to the war in South Africa/compiled and edited for the Department of Defence, A.J. Mullett, Govt. Printer Melbourne 1911, pp. 214-225 and pp. 279-281. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015070381432&view=1up&seq=4. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

[14] Avoca Mail, 16 January 1900, 19 January 1900, 23 January 1900, 30 January 1900, 16 February 1900, 13 March 1900, 20 March 1900, 23 March 1900, 30 March 1900, 3 April 1900, 20 April 1900, 24 April 1900, 11 May 1900, 15 May 1900, 18 May 1900, 25 May 1900, 29 May 1900, 26 June 1900, 3 August 1900, 7 August 1900, 10 August 1900, 14 August 1900, 24 August 1900, 11 September 1900, 18 September 1900, 19 October 1900, 23 October 1900, 6 November 1900, 9 November 1900, 13 November 1900, 20 November 1900, 4 December 1900,

[15] Argus, 11 January 1901, p. 5. Retrieved 3 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article10529341.

[16] Age, 10 January 1901, p. 8. Retrieved 3 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article196069777.

[17] Argus, 30 January 1901, p. 9. Retrieved 3 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article10532425.

[18] Age, 16 February 1901, p. 9.

[19] Age, 29 May 1902, p. 5. Retrieved 3 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article199400394.

[20] Register, 10 September 1902, p. 5. Retrieved 3 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article56258788.

[21] Tasmanian News, 13 September 1902, p. 2. Retrieved 4 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article176637209 and Age, 16 September 1902, p. 4. Retrieved 4 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article187629414.

[22] Herald, 5 July 1904, p. 3. Retrieved 3 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article241917076.

[23] Age, 2 September 1904, p. 5. Retrieved 3 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article189438382.

[24] Punch, 2 August 1906, p. 26. Retrieved 3 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article175377154.

[25] The Register (Adelaide), 16 September 1907, p. 8.

[26] Argus, 15 October 1932, p. 26.

[27] Maffra Spectator, 18 December 1913, p. 3.

[28] Western Mail, 23 September 1926, p. 3 and 17 July 1930, p. 35.

[29] Victoria’s Contribution to WW1, ANZAC Centenary, 2014 – 2018, Sharing Victoria’s Stories and Making Contributions, http://anzaccentenary.vic.gov.au/history/victorias-contribution-wwi/, accessed 29 March 2017.

[30] Charles Henry Raitt enlisted in April 1915 and was torpedoed whilst being transported on the Southland to Gallipoli in September 1915 where he became ill with dysentery, gallstones and jaundice and was invalided to Australia in January 1916. In late 1917, he served again as a commander on a troopship to England but was terminated on his return in January 1918. Argus, 22 November 1915, p. 8. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1580792. Maryborough and Dunolly Advertiser, 10 January 1916, p. 4. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/ART09829/. https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=8025226. Retrieved 8 May 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article90593144

[31] Maryborough and Dunolly Advertiser, 26 August 1914, p. 3.

[32] Gus Eberling (sic), First World War Embarkation Roll, Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 6 May 2020 from https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/R1837409.

[33] Anne Young, ‘First volunteers in Broadmeadows camp’, Avoca during World War 1, http://avocaww1.blogspot.com.au/2014/08/first-volunteers-in-broadmeadows-camp.html. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

[34] Lieutenant Colonel William Kinsey Bolton, Australian War Memorial, https://www.awm.gov.au/people/P10679811/#biography (accessed 1 April 2017) and J. N. I. Dawes, ‘Bolton, William Kinsey (1860–1941)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bolton-william-kinsey-5283, published first in hardcopy 1979, (accessed 4 April 2017).

[35] National Archives of Australia: B2455, SERGEANT, John Edwin. Retrieved 28 April 2020, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=11619241. He is buried at Shell Green Cemetery, Artillery Road Plot 6 at Gallipoli. Commonwealth War Graves Commission: https://www.cwgc.org/find/find-war-dead/results/?cemetery=SHELL+GREEN+CEMETERY&casualtypagenumber=16

[36] Eberling (sic), Gus, Mention in Despatches, Australian War Memorial, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/P10440684 and https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1627998/ Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, 27 January 1916, p. 156, position 105 and London Gazette, 5 November 1915, p. 11002, position 73, and https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1542473/, accessed 1 April 2017.

[37] St Arnaud Mercury, 16 June 1915, p. 2.

[38] Avoca Free Press and Farmers’ and Miners’ Journal, 25 December 1915, p. 2.

[39] Captain William Thomas Yates fought at Gallipoli and later won a Distinguished Service Order and was mentioned in despatches when fighting in France. NAA: B2455, William Thomas Yates. https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=3454320 . Retrieved 30 April 2020.

[40] Avoca Mail, 4 February 1916, p. 2.

[41] Ballarat Courier, 21 March 1916, p. 3.

[42] Avoca Free Press and Farmers’ and Miners’ Journal, 22 March 1916, p. 2.

[43] Bendigonian, 8 June 1916, p. 10. Retrieved 28 April 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article91388285.

[44] Bendigo Advertiser, 9 June 1916, p. 3. Retrieved 28 April 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article89980506.

[45] Bendigo Advertiser, 20 June 1916, p. 3. Retrieved 28 April 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article89981905.

[46] Bendigo Advertiser, 3 October 1916, p. 8.

[47] Bendigo Independent, 19 July 1916, p. 3.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ballarat Courier, 29 August 1916, p. 3. Retrieved 28 April 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article74680876.

[50] Senate, Official Hansard, No. 38, 1916, Friday, 22 September 1916, p. 8827. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/hansard80/hansards80/1916-09-22/toc_pdf/19160922_senate_6_80.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22hansard80/hansards80/1916-09-22/0011%22. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

[51] Punch, 19 October 1916, p. 614.

[52] Bendigonian, 20 June 1918, p. 22. Retrieved 28 April 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article89094481.

[53] Avoca Free Press and Farmers’ and Miners’ Journal, 13 December 1916. , p. 3. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article151686028

[54] Bendigonian, 23 August 1917, p. 25. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article90844194.

[55] Avoca Mail, 28 August 1917, p. 2. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article152146482.

[56] Avoca Free Press and Farmers’ and Miners’ Journal, 2 October 1918, p. 2. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article151681887.

[57] Ballarat Star, 2 February 1920, p. 4. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article212055936.

[58] Age, 7 December 1921, p. 16. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article204271481.

[59] Ballarat Star, 11 August 1920, p. 4. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article211915220.

[60] National Archives of Australia, Ebeling, G., B2455, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=3533626, accessed 1 April 2017.

[61] Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Vivian Deeble, son of Joseph Deeble of Ballarat, enlisted as a Captain on 24 October 1914 and embarked as a Major with the 8th Light Horse Regiment on the transport Star of Victoria on 25 February 1915. After serving in Egypt for some time, he proceeded to Gallipoli with his unit on 16 May. He commanded the second wave of the famous charge on Walker’s Ridge (the Nek) on 7 August 1915 and was promoted on that day to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and to command his regiment. On 3 September he was admitted to hospital sick and invalided to England on 21 June 1916. On 14 March 1917 he was appointed to the command of the 69th Battalion, which he organised and trained until its dissolution in September 1917. On 23 October 1917 he proceeded to France and was given command of the 48th Battalion. On 28 March 1918 he returned to England on duty. He returned to Australia in charge of troops on the transport Gaika on 5 July and was discharged on the 22nd of the same month. Prior to enlisting he was teaching at the Essendon High School. http://empirecall.pbworks.com/w/page/27047096/Deeble-A-V-Major, accessed 18 November 2017. Also, National Archives of Australia (NAA): B2455, DEEBLE A V

[62] Formerly a well-known Melbourne businessman, White had insisted upon leading the first line of his regiment, the chance that such a leader would survive on such a day was obviously remote. Evidently realising this, he had gone to the brigade office ten minutes before the start and held out his hand to the brigade major, Antill. ‘Good-bye,’ he said simply. C.E.W. Bean, The Story of Anzac: From 4 May, 1915 to the Evacuation, (11th edition, 1941), pp. 607-624, cited in http://alh-research.tripod.com/Light_Horse/index.blog/1919271/the-nek-beans-account/# , accessed 24 December 2019.

[63] National Archives of Australia, B2455, SPROAT JAMES

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ancestry Australia, Electoral Rolls, 1903-1980 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Australian Electoral Commission. [Electoral roll]. https://www.ancestry.com.au/, accessed 24 December 2019.

[66] Australian War Memorial, Cecil Harwood Locke Davies, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/R1604835, accessed 20 December 2019.

[67] Ernest Albert Harris enlisted for service during the First World War with the 21st Battalion, serving with this unit at Gallipoli. He returned to Australia in early 1916 as the commanding officer of the newly raised 59th Battalion and was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel (Lt Col). Shortly after arriving in France on 19 July 1916, Lt. Col. Harris suffered shell shock at the Battle of Fromelles and was evacuated to England. He was medically discharged in October 1916. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C2083536, accessed 19 November 2017.

[68] Victorian Government Gazette, 10 June 1931 p. 1761.

[69] National Archives of Australia, White Army A395, NN. Browne, Roland Seymour, Inspector, b 1887, joined public service 1921, Inspector, Commonwealth Investigation Branch, Melbourne (1921–43), later served in Military Intelligence. Roger Douglas, ‘Saving Australia from Sedition: Customs, the Attorney-General’s Department and the Administration of Peacetime Political Censorship’, Federal Law Review, Faculty of Law, Australian National University, Volume 30, No. 1, 2002, p.175.

[70] Victoria Police Gazette, 13 January 1910, p. 27 and 23 January 1913, p. 53.

[71] National Archives of Australia, CRS A395, 1 May, 28 April; Public Records Office of Victoria, Chief Secretary 1931/A3586, cited in Michael Cathcart, The White Army of 1931: Origins and Legitimations, Unpublished Master of Arts Thesis, Australian National University, June 1985, p. 35.

[72] National Archives of Australia, White Army A395, NN

[73] CRS A395, 1 May, cited in Ibid.

[74] Tout-Smith, D. (2003) Hibernian Australian Catholic Benefit Society, Museum Victoria Collections, http://collections.museumvictoria.com.au/articles/2036, accessed 18 December 2017.

[75] James Griffin, ‘Mannix, Daniel (1864–1963)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/mannix-daniel-7478/text13033, published first in hardcopy 1986, accessed online 18 December 2019.

[76] Anne Beggs Sunter, ‘Duggan, Bernard Oscar Charles (1887–1963)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/duggan-bernard-oscar-charles-6031/text10309, published first in hardcopy 1981, accessed online 20 December 2019.

[77] National Archives of Australia, B2455, MCILROY W A

[78] Captain Duggan embarked aboard HMAT Ulysses on 8 May 1915. On 12 March 1916 he was promoted to the rank of Major. On 16 June 1917 he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, Commanding Officer of the 21st Battalion. On 1 January 1918 he was awarded a DSO for ‘conspicuously good work as Senior Major’ at Pozieres in July/August of 1916 and at Flers in November 1916. On 2 April 1919 he was awarded a Bar to the Distinguished Service Order for the Battalion attack at Montbrehain on 5 October 1918 where ‘during the attack he set a fine example of zeal and energy to his command’. On 25 March 1919, he returned to Australia and his appointment was terminated on 4 October 1919. Photo taken Broadmeadows, Victoria, Melbourne, c 15 May 1915. Australian War Memorial, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/DA08667/, accessed 14 March 2017.

[79] ‘The Late Father John Francis Coughlin’, Advocate (Melbourne), 27 January 1949, p. 7.

[80] Canon Reverend Edmund Henry Hoffman officiated at Gus Ebeling’s well attended funeral held at St. John the Divine’s Anglican Church in Avoca in early July 1943. Age, Melbourne, 3 July 1943, p. 3.

[81] National Archives of Australia, White Army A395, NN.

[82] David Horner, ‘Blamey, Sir Thomas Albert (1884–1951)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/blamey-sir-thomas-albert-9523/text16767, published first in hardcopy 1993, accessed online 5 May 2020.

[83] Michael Cathcart, The White Army of 1931: Origins and Legitimations, p. 6.

[84] Argus, 7 March 1931, p. 19

[85] Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Lateline, Broadcast: 2 September 2003, ‘Carr talks about return of POWs from Japan’, http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/content/2003/s937662.htm, accessed 30 December 2013.

[86] Michael Cathcart, Defending the National Tuckshop: Australia’s Secret Army of Intrigue of 1931, McPhee Gribble Publishers, Melbourne, 1988, p. 5.

[87] Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 7591/P0002 unit 419, item 106/509, Claus Ebeling. Date of grant: 01 May 1908; Date of death: 26 Oct 1907; Occupation: Farmer; Residence: Avoca, http://access.prov.vic.gov.au/public/component/daPublicBaseContainer?component=daViewItem&entityId=5138985631 , accessed 8 April 2017 and Geoff Browne, ‘Herring, Sir Edmund Francis (Ned) (1892–1982)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/herring-sir-edmund-francis-ned-12626/text22747, accessed 8 April 2017.

[88] Avoca Mail, 18 July 1893, p. 2.

[89] Michael Cathcart, op cit.

[90] A. J. Sweeting, ‘Brand, Charles Henry (1873–1961)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/brand-charles-henry-5338/text9025, published first in hardcopy 1979, accessed 18 December 2019.

[91] National Archives of Australia, Ebeling, G., B2455, op cit.

[92] Avoca & District Historical Society Inc, Ebeling Cash Store, https://www.facebook.com/717061235023833/photos/can-anybody-tell-us-where-in-high-street-avoca-the-ebeling-cash-store-was-situat/1099547930108493/ 13 May 2016 and 5 November 2018 https://www.facebook.com/717061235023833/photos/a.717874164942540/1099547930108493/?type=3&comment_id=2065710656825544, accessed 23 December 2019.

[93] “Family Notices” The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.: 1848 – 1957) 12 July 1943: 2. Web. 19 Dec 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article11791370>. and “Family Notices” The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957) 9 July 1943: 2. Web. 19 Dec 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article11794705>.

Contact Peter Vodicka about this article.