Maestro John Monash is not so much a biography or military history book as a long essay making the argument to posthumously promote Sir John Monash to the rank of Field Marshal. The bulk of Maestro John Monash does provide a synopsis of Monash’s life in the first nine of its 18 chapters, but the author’s aim is to rally and mobilise a movement to lobby the Prime Minister and Governor-General to make such a decision.

The Honourable Tim Fischer, AC, is a former Australian Deputy Prime Minister (Howard Government, 1996 – 1999) and leader of the Federal National Party. As a National Serviceman, he served as a rifle platoon commander with 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, in Vietnam in 1968 – 1969.

Fischer’s proposition is laced throughout the first nine chapters of Maestro John Monash and then argued from almost every angle in the second nine chapters. The reader is left in no doubt that Fischer is a strong advocate of Sir John Monash and that he believes that Monash has been denied ‘proper’ recognition for his wartime achievements. Related to this, Fischer also believes that the Australian contribution to the Allied war effort is also inadequately recognised by non-Australian historians. In this context, it should be noted that the Australian Imperial Force comprise only 1 per cent of the total number of personnel mobilized by the Allied powers, and that Monash was but one of twenty corps commanders in the British Expeditionary Force.

Fischer cites two main reasons why Monash has been denied proper recognition: in the historical sense, because of the negative bias of official historian, C. E. W. Bean; and in the form of promotion, by the concern of Prime Minister Billy Hughes about creating a potential political rival. Behind at least one of these biases Fischer also attributes anti-Semitism. Fischer’s research is not detailed and his evidence to support these claims is not backed up by appropriate end notes citing references. Further, his narrative often drifts onto secondary general war history topics.

To his credit, however, in the style of an argumentative essay, Fischer does address arguments against his proposition, but despite inviting readers to ‘reach their own conclusions’ his bias is clear. On balance, however, it would seem that Monash’s wartime performance was generously recognised – not the least by his knighting (to Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath) in the field by the King George V on 12 August 1918, appointment as a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George on 1 January 1919, and by his promotion from Lieutenant-General to General by Prime Minister Scullin on 11 November 1929. More intangibly, and perhaps more significantly, biographer Geoffrey Serle suggested that Monash’s “presence and prestige … made anti-Semitism … impossible in Australia”.

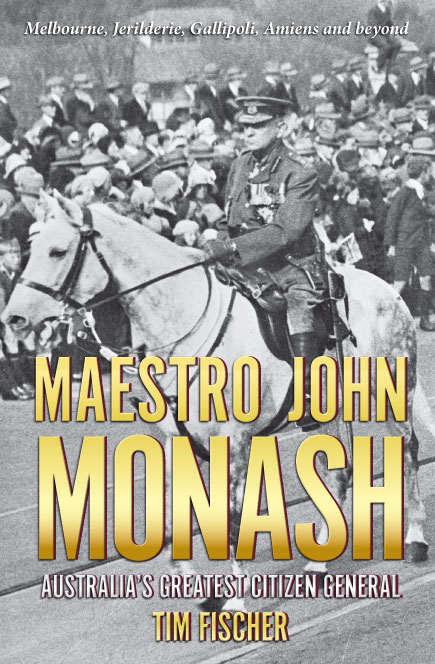

Maestro John Monash contains a foreword by the Honourable Josh Frydenberg, MP, who strongly supports the proposition. Included are a good number of photographs (many showing how Monash has been recognised) and two maps showing the Battles of Hamel on 4 July 1918 and the ‘Battle of Greater Amiens’ on 8 August 1918. There are also a series of rudimentary sketches produced by Fischer’s son which I, uncharitably, felt detracted from the quality of the product.

There are three appendices: the last two are a Buckingham Palace Banquet Seating Plan from 27 December 1918 and a copy of the letter providing it to the author. Appendix A is advice to readers to make representations in support of Fischer’s proposition – which drifts into repeating arguments in favour of the proposition. In all, if the book is intended to make the case to those who might be against the proposition or ambivalent then it could have been more logically and succinctly presented.

There is no argument that Sir John Monash was an important figure, but as a reader who is ambivalent on the proposition to posthumously promote Sir John Monash to the rank of Field Marshal, on balance, I did not find the argument convincing. The main question to ask is “what would it really achieve?” While Fischer makes several arguments in support of the proposition, I remain unconvinced that it would be seen as much more than a hollow Anzac Centenary political revisionist gesture.

In all, Maestro John Monash is neither a biography nor a balanced military history book, so I fear that its appeal will be limited to those who are already Monash advocates.

Contact Marcus Fielding about this article.