Australia’s naval heroes have not received the attention they deserved since the formation of the Royal Australian Navy, over more than a century ago.

Several fought so bravely, they should have received a Victoria Cross, but did not. Some were recognised with minor honours – some with nothing at all. This article proposes a method for giving them more recognition.

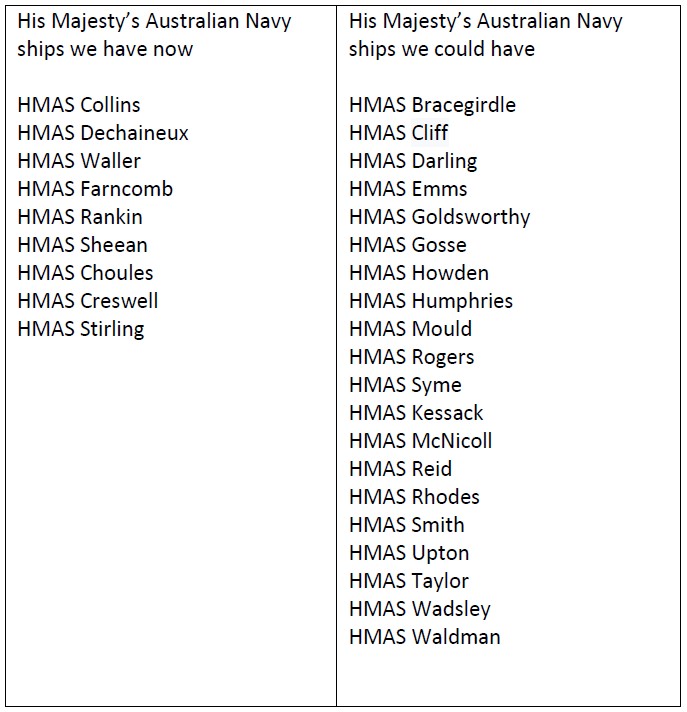

Some of our naval heroes have achieved fame which has endured in a permanent and visible way. WWII men John Collins, Emile Dechaineux, Hec Waller, Harold Farncomb, Robert Rankin, and Teddy Sheean have all had submarines named after them. Sheean especially is now a household name, having received a long overdue Victoria Cross in 2020, 78 years after his gallant last stand on the corvette HMAS Armidale.

It is worth noting though, that Australian naval personnel have been somewhat short-changed by the arrangements which were in place for World War II in regard to bravery honours and awards.

It is worth noting though, that Australian naval personnel have been somewhat short-changed by the arrangements which were in place for World War II in regard to bravery honours and awards.

In those days to recommend decorations within the RAN was very difficult – more so than in the (parent British) Royal Navy, with more restrictions on Australian ship commanders as to what their members could be recommended for.

There were only two classes of posthumous award in WWII: the Victoria Cross and the Mention In Despatches. Posthumous foreign awards were not permitted and RAN gallantry awards were determined by the British Admiralty.

It should further be noted that this situation was unique to the RAN: the Army and the Royal Australian Air Force had their bravery decorations processed through the Australian system – a much easier and more favourable situation than one being processed by the British Admiralty in a country fighting for its life against Germany In summary we can conclude that if this unfair situation had not been in place, the RAN may well have received other Victoria Crosses – and the argument that more ships should be named after heroic Australians made all the easier.

Only one other Australian naval veteran has had a vessel named after him. In a departure from tradition and usual practise, the country’s last veteran of World War I had his name bestowed on HMAS Choules in 2011. Claude Choules started his naval service in the Royal Navy, in his case in 1916. He came to Australia on loan in 1926 and decided to transfer to the RAN. He was a member of the commissioning crew of HMAS Canberra in 1928 and in 1932 became a Chief Petty Officer (Torpedo) and anti-submarine instructor.

During WWII Choules was a Torpedo Officer in Fremantle and the Chief Demolition Officer on the west coast. He transferred to the Naval Dockyard Police after the war so that he could continue to serve, finally retiring in 1956. Although he gave sterling service, the use of his name seems more to testimony he was one of the final servicemen resident in Australia who saw WWI service.

Only seven naval servicemen have had vessels named after them, the Collins-class being the beginning of that practise. However, there have been shore bases named after people, as opposed to rivers, states, and places, which constitute most of the rest of the many hundreds of vessels which have seen service.

For example, HMAS Creswell is named after the “founding father” of the RAN, William Rooke Creswell, originally of the RN, but a fierce advocate for Australia to have its own force, back in the days when the states were so afraid of foreign attack that they had formed separate colonial navies. HMAS Stirling honours the name of Captain James Stirling RN, the officer who landed on Garden Island in 1827. Two years later he founded the first European settlement in Western Australia. Such large shore bases are commissioned as ships in navies, so we should include these two sterling servicemen with the group.

Why not extend this practise a lot further? The newly evolved Cape-class patrol boats, for example, are all named after prominent capes around the country. Why not change these into ships named after people? Or give a future class of vessels such titles? For some reason, we seem reluctant to do this. The Americans, by contrast, have hundreds of ships named after people, and even the RAN’s parent navy – Britain’s Royal Navy – has had a lot.

There are many heroes of our own force to choose from.

Francis Emms was a ship’s cook who performed valiantly at his Action Station when the first Japanese air raid struck Darwin. On board the small ship HMAS Kara Kara, he manned his machinegun until he fell, wounded from the strafing of the circling Zeroes. He refused to leave his post to be treated until the enemy had broken off the action. He later died of his wounds.

Ronald “Buck” Taylor was in an action very like that involving Teddy Sheean. In March 1942 HMAS Yarra and her three merchant vessels were attacked by a Japanese surface flotilla. Yarra, a sloop, had fire capacities far below the enemy both in weight of shell fired and in range. Nevertheless, she charged the enemy as her captain, Lieutenant Commander Robert Rankin, ordered the ship to engage. Ron Taylor kept his gun firing, ignoring the order to abandon ship. He died without leaving his post.

Several RAN members have been awarded the George Cross – the second highest honour for bravery, just not “in the face of the enemy” – in WWII. Mine warfare demanded the highest examples of cold-blooded courage and four of the Navy’s best took that bravery into everyday operations in mine warfare defusing and disposal: Leon Goldsworthy, George Gosse, John Mould, and Hugh Syme – the latter two also receiving the George Medal.

Jonathan “Buck” Rogers – the nickname comes from a popular science-fiction character – was a hero from HMAS Voyager, tragically rammed by the aircraft carrier Melbourne in 1964 off Jervis Bay. Chief Petty Officer Rogers united those trapped in the forward section of the destroyer, still afloat, before after some time its inexorable flooding with water sent it to the seabed. Rogers is a George Cross recipient; he already held the Distinguished Service Medal for ‘coolness and leadership’ under enemy fire during an action off Dunkirk, France, on the night of 23/24 May 1944.

The George Medal was given to others:

• Petty Officer John Humphries. Awarded the Medal on 17 February 1942, the citation reading “For skill, and undaunted devotion to duty in hazardous diving operations”.

• Lieutenant Geoffrey John Cliff, RANVR. Awarded the Medal in 1942 for work undertaken defusing mines in London.

• Lieutenant James Kessack, RANVR. A mine clearer, he died in the execution of his duty on 28 April 1941.

• Lieutenant Commander Alan McNicoll RAN., Received the Medal for “gallantry and undaunted devotion to duty. In 1940 in the captured Italian submarine Galileo Galilei, McNicoll removed the inertia pistols from eight corroded torpedoes.”

• Lieutenant Howard Dudley Reid RANVR. First awarded for “gallantry and undaunted devotion to duty” in mine disposal between December 1940 to January 1941. Secondly, for mine disposal in Glasgow in August 1941.

• Lieutenant Nelson Smith RANVR. “Awarded for gallantry and undaunted devotion to duty. In March 1941, rendered safe eight bombs in London.”

• Lieutenant Keith Upton RANVR. As a mine clearer, showed ‘the highest courage, devotion to duty and remarkable ingenuity, his initiative and gallantry marking him out among the personnel of this special section’.

• Lieutenant Herbert Wadsley RANVR. First awarded the Medal in 1940 for mine disposal in London. A bar was awarded in 1942 for bomb and mine disposal in Portsmouth in 1941.

• Lieutenant Commander Neil Waldman RNR. Commanding minesweepers in North Africa, including the port of Tripoli, where the Medal was awarded for great bravery and undaunted devotion to duty.

There are many others who could join a list of possible Navy people after whom a ship or base could be named.

Ordinary Seaman Ian Rhodes, a RAN Volunteer Reserve sailor, was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal for courage in action on 23 May 1941, when HMS Kashmir was sunk during operations to defend Crete. Posted to the RN, Rhodes was part of the crew for the aft port Oerlikon gun. With the water rising around the weapon as the ship sank, and under fire from German aircraft which strafed the ship and survivors already in the sea, Rhodes climbed up to the weapon on the other side of the ship and commenced returning fire, shooting down an aircraft. For his courage in action, he was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, the award for gallantry second only to the Victoria Cross for sailors, and the only Australian sailor to receive the decoration through both world wars.

Harry Howden was one of the Navy’s best fighting captains. Howden’s command of the cruiser HMAS Hobart in WWII was characterised by the energy and aggressiveness of a captain who resembles the famous General Patton in his willingness to engage with the enemy. Mercurial but meticulous, he was much respected and even worshipped by his ship’s company. As a fighting captain he was known for his high-speed handling of Hobart, and commanded her in much action through the war until brought down by sickness.

Warwick Bracegirdle, a gunnery officer, was perhaps the best product of that branch the RAN ever produced. He served through WWII where as a lieutenant he was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross for “whole hearted devotion to duty and high personal courage” – particularly during an air raid at Piraeus, Greece, when towing an ammunition lighter away from a burning ship, which exploded nearly killing him and another officer.

Appointed to the heavy cruiser HMAS Shropshire, Bracegirdle developed a burst method for firing heavy guns in Anti-Aircraft work. He was later awarded a bar to his DSC and twice mentioned in dispatches. He served on after the war and then in the Korean conflict where he commanded the destroyer HMAS Bataan. For his Korean War service Bracegirdle was awarded a second bar to his DSC – thus the equivalent of being awarded the medal three times – and the United States Legion of Merit.

The career of Stanley Darling, sinking U-Boats, and then quietly retiring from combat to take on the mere matter of a Sydney-to-Hobart yacht race year after year, reads like a Boy’s Own adventure tale. Serving in Europe, he was appointed in command of the frigate HMS Loch Killin as part of Captain Frederic ‘Johnnie’ Walker’s 2nd Escort Group of anti-submarine frigates. This group of six frigates became renowned as a deadly and greatly feared submarine killer group in the Atlantic campaign. Darling’s frigate was accredited with sinking three U-Boats in the war – an unusually high score in a war where most ships never had an anti-submarine attack confirmed as a kill.

For some reason the Royal Australian Navy has been loath to carry the practise forward of naming ships and bases after men. (Many of the Victoria Cross holders of the country – 96 Army and four RAAF – are remembered in rest stops on the Hume Highway: there has yet been no arrangement made yet for Teddy Sheean’s name to be added to them.) But there is no real reason why this is not the practise, and it is not unusual in navies. In what might be termed our two closest allied navies – that of Britain, and that of the United States of America – have in general, shown a different attitude towards granting its armed forces’ members’ decorations, and recognizing their service, than we have.

For example, the USA has named ships after military personnel with an enthusiasm not often imitated by other countries. This can even border on the unusual: one WWII vessel was named USS The Sullivans, to commemorate the five Sullivan brothers from Iowa who had asked to serve together, and who had all been killed when their cruiser USS Juneau was torpedoed in 1942. A warship of the name was commissioned the following year.

The practise of naming ships after people was developed from the early days of the US Republic, and practised prolifically ever since. Presidents of the United States have featured strongly, and recently a new aircraft carrier named after President George HW Bush, a WWII veteran, was commissioned.

In general the US practise sees vessels named after a person who has died, but this is not always the case. Foreigners have also been named: USS Winston S Churchill was commissioned by President Carter, for example, who in an example of the previous point had a Seawolf submarine named after him – he is the only US president to have qualified on submarines. Another US president who served in the Navy was “JFK” – the aircraft carrier USS John F Kennedy is named after him.

In Australia, no prime minister has ever served in the Navy, although several have in the Army and RAAF. One-quarter of Australia’s prime ministers enlisted for military service at some point in their lives. This includes four who saw active service: Stanley Bruce, John Gorton, Earle Page and Gough Whitlam. Two – Bruce and Gorton – were wounded during active service.

US Army forces bases are also prolifically named after serving personnel. The writer was interested to see a firing range in Iraq, on which he practised shooting twice a week in 2006 during the war, was named after a recently deceased soldier who had died in combat, in that very same conflict.

Fort Lee, in Virginia, is named for Robert E Lee, the Civil War Confederate leader. Fort Benning in Georgia is named for Henry Benning, a State Supreme Court associate justice who became one of Lee’s subordinates. Fort Sam Houston, a US Army installation in San Antonio, Texas, is named in honour of Sam Houston, the first (and third) president of the Republic of Texas, whose victory at the Battle of San Jacinto secured the independence of Texas from Mexico.

US Air Forces bases follow the tradition. Dyess Air Force Base, for example, is named in honour of Lieutenant Colonel William Dyess, a Bataan Death March survivor.

Australia’s parent Navy in Britain has also been prolific in naming warships after people. Perhaps the first vessel named after a person dates from 1418, when Britain’s King Henry V paid the Bishop of Bangor five pounds for christening the largest warship of the time, the Henri Grace A Dieu, which translated as Henry By Grace Of God. This certainly reminded the general public that he was appointed by divine right, an important topic around that time.

A brief sample of other ships in the Royal Navy includes many named in the long war between France and Britain which culminated at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Towards the end of the war, the RN began to name more ships for people, including contemporary names. The Nelson class of 120 gunships also included vessels named for military people: HMS Howe – after Admiral Richard Howe – and Saint Vincent – named after Lord St Vincent – after Admiral of the Fleet John Jervis, after whom Jervis Bay is named; and one named after royalty, the Prince Regent. There were major warships named for military men: Wellington, Wellesley – both named after the Army general who was the victor of Waterloo – Duncan, Cornwallis, Benbow, Barham, Drake, Hawke, Melville, and Pitt after the prime minister.

It would be likely that the RAN will continue the names of the seven people who have ships afloat named after them. The usual practise sees the more notable names continued – for example there have been four HMAS Sydney’s so far. Some names are seemingly destined to be only used once. For example, HMAS Wyatt Earp will be unlikely to be used again. This vessel, purchased from trade, served in WWII under a different name, but then was used in her original duty of Antarctic supply under her earlier title. As the name commemorates a well-known American West lawman it would be unlikely. However, like many others, HMAS Tasmania has only been used once. It is worth noting there is considerable enthusiasm for Navy to continue using old names, with many “ship associations” advocating for their cause.

In conclusion, there are a host of alternative names – those of its heroes – which the RAN could use to name ships. By doing so it would not only commemorate the past, but also celebrate the actions which its personnel are sometimes called upon in battle – and therefore show that their actions are laudable and to be emulated.

This action, of changing the practise of naming ship after people, should be argued for until it becomes reality. In the words of the motto of the submarine Sheean – Fight On.

-o-o-O-o-o-

Dr Tom Lewis OAM is the author of 20 books. A veteran of the Royal Australian Navy, he was decorated with the Order of Australia Medal for services to military history. He served in Iraq as an intelligence analyst and the commander of a US Forces unit. His books mostly deal with World War II, but also cover the actuality of battlefield behaviour in Lethality in Combat, and middle ages warfare in Medieval Military Combat. His most recent work is Attack on Sydney, a study of the failures in command combating the midget submarine attack of 1942.

Contact MHHV Friend about this article.