The story of HM Australian Submarine AE2 in the Dardanelles campaign typically ends on April 30, 1915 when the stricken submarine, after penetrating the Narrows and ‘running amok’ against the Turkish warships was severely damaged and forced to surface. The valiant crew abandoned ship before scuttling it in the Sea of Marmara. The vessel itself has been the subject of searches and debate ever since its discovery in 1998, but as the brave crew was taken into captivity by the Turks another less known chapter of the story was set to unfold. A chapter that for three members of the crew would curiously end in northern Baghdad.

AE2 crew member Able Seaman Albert Knaggs kept a diary and from this account and other sources it is possible to partly reconstruct their experiences in captivity.

The Turkish torpedo boat Sultan Hisar took the 32 crew members on board and proceeded to Gelibolu (Gallipoli). They made fast alongside a hospital ship and were interviewed by General Otto Liman von Sanders who was the German General in command of the Ottoman Army. At 8 p.m. they proceeded on the Sultan Hisar to Constantinople where they arrived the next morning on May 1, 1915.

Able Seaman Knaggs’ diary provides a detailed account of the crew’s experiences on arrival in Constantinople after what appears to have been an uncomfortable trip:

‘After being nearly eaten alive with bugs and lice which this country is noted for. Before leaving the boat we were supplied with soldier suits, overcoats, slippers and red fezzes to march through the streets of Constantinople to prison. The officers rode in a carriage. On arrival we were put into a small room in the basement and food brought in which was not fit for pigs. Some of us were taken out one by one to be interviewed by an officer who spoke English for information regarding our movements while in the Sea of Marmara and questions about the boat, but he didn’t learn anything good for him. So about 10 of us were interviewed out of the crew, but we were not allowed back into the same room. As each man finished he was marched into another room and we were not allowed to see or speak to the remainder. That evening we were served out with Turkish sailor suits and a pair of socks. We had nothing to sleep on but the bare floor and our overcoats to cover us.’

On 5 May the crew departed Constantinople and was transported by train over the next three days to a POW camp at Afyon Kara Hisar in the central highlands of Anatolia. There they met Russian merchant sailors and the crew of the French submarine Saphir, as well as the surviving crew members of HM Submarine E12 who had been captured at the southern end of the Dardanelles on April 17, 1915.

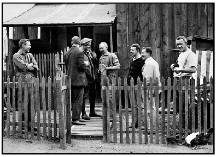

The camp at Afyon Kara Hisar was the clearing and distribution centre for all other Turkish POW camps. Living and sanitary conditions at the camp were poor and the POWs were largely confined to cramped buildings. Only after two months of confinement were they allowed out for two hours exercise each day. A photograph of Australian and British POWs at Afyon Kara Hisar taken about this time shows them wearing beards due to the scarcity of soap and the cold weather.

In early June 1915, as the weather warmed, the POWs were put to work constructing roads. Long days of manual labour were followed by cold nights camped in tents. When food was not provided by their Turkish masters the group refused to work. In late July they returned to the camp at Afyon Kara Hisar where they discovered an outbreak of typhoid amongst the Russians. In order to stem the outbreak the POWs were inoculated and given new clothes. Accommodation blocks were disinfected washed with lime and new hay filled mattresses were issued.

In early August Knaggs recorded a visit to the camp by the U.S. Ambassador. The Ambassador inspected their living conditions and listened to their complaints. He also brought them soap, pipes, tobacco, underclothes and a quantity of insect powder. Knaggs also notes that they received some Turkish money, which may have been part of a disbursement arrangement set up by Chief Petty Officer Harry Abbot.

In late August 1915 they recommenced work constructing the roads, but a few days later stopped due another typhoid outbreak. They were placed in quarantine for two weeks and undertook more whitewashing and disinfecting in an effort to stamp out the disease.

Knaggs’ diary picks up again in early October when the ratings were moved by horse van to Angora (Ankara) about 200 kilometres east of Afyon Kara Hisar. The three HMAS AE2 officers remained at Afyon Kara Hisar. Staying temporarily in a prison at Angora the crew met up with other French and British POWs including the crew of HM Submarine E7.

On October 14, 274 allied POWs began a four day 80 kilometre long march to Cankiri north east of Angora. Knaggs recorded: ‘Many of the prisoners were suffering from wounds, not having been long out of hospital and the march being on bread and water. Many of the best amongst us fell out with some of them to help along the way.’ At Cankiri the POWs occupied an old training barracks which Knaggs found to be: ‘…very acceptable, but cold and draughty and full of vermin, lice etc. as usual. The barracks had one water tap in the yard for all hands to wash, no soap being provided and no working clothes.’ That night they gratefully found beds and quilts to lie on.

At the end of November a heavy snow fell. On December 22, 1915 a representative of Red Crescent Society visited the camp to find out what clothes were needed and to hear all complaints. Snapshots were taken of the POWs.

During Christmas the Muslim Turks were clearly prepared to let their Christian prisoners celebrate. Knaggs recorded that…

‘Christmas Day was made as bright as possible by our Turkish officers who gave us permission to play football outside in a field. We played a match Navy versus Army in which Army won 4 goals to 1. A concert was held amongst ourselves in the evening. On Boxing Day another football match took place between AE2 versus E7 which ended in a drawn game. On New Year’s Day the Commandant visited us and wished us a Happy New Year and hoped we would soon be home with our families. The Australians played rugby against the Scottish Borderers, and the Australians won 6 points to 3. In the evening another concert was held. On January 4 we received £1 from Camp Commandant and also received Xmas puddings, sweets and cigarettes from the Red Cross Society.’

On January 6, 1916, Knaggs records news that British and French forces had evacuated the Gallipoli Peninsula. Given that the withdrawal of the ANZACs was only completed on December 20, 1915 and Cape Helles remained occupied until January 9, 1916 it seems that the Turks must have been quick to relay this news to the POWs. After such news morale within the camps POW community must have sunk pretty low.

After only a couple of months at Cankiri the POWs began a march back along snow covered roads to Angora on January 17, 1916. On arrival they were housed in different quarters around the town. A week later in the evening they were marched down to the train station and began a three day journey to the town of Pozanti standing at the entrance of a pass across the Toros (Taurus) Mountains in southern Anadolu (Anatolia). Knaggs records, “Here we are under German and Swiss engineers for work and receive 8 piastres per day for food which we buy our own doing away with the Turkish food. We are allowed plenty of Liberty no sentries are allowed to interfere with us as long as things run smooth. The work here consists of drilling and blasting tunnels, navvying [labouring], clerks, carpenters, electricians etc and odd jobs, extra money being paid monthly according to abilities at work. The name of the place being Belemedik.”

Belemedik is 15 kilometres from the township of Pozanti and was one of about a dozen camps set up in southern Turkey to have POWs work on building sections of the Berlin to Baghdad Railway. Belemedik camp was set on the banks of a river and deep in a valley under tall mountains. Construction of the strategically important and controversial railway began in 1903. By the start of the First World War many sections had not yet been completed and this hampered the Ottoman Empire’s efforts to supply and reinforce the Mesopotamian Front. The unfinished sections through the Toros Mountains were technically difficult and required considerable effort to construct. Allied POWs were put to the task of blasting twelve tunnels, milling timber and laying railroad track. As an indication of the railway’s significance, Enver Pasha, the Turkish Minister for War, visited on February 18, 1916 to inspect the works.

On April 10 Knaggs recorded a rumour that Lieutenant Commander Stoker (the AE2′s Captain) and two other officers escaped from Afyon Kara Hisar. On May 8 Knaggs notes word that had been recaptured. On Easter Monday, April 24 Knaggs records that he managed to get ‘plenty drunk’. On April 30 he notes the anniversary of their capture and his wife Annie’s birthday.

Over the months Knaggs records a steady stream of deaths from illness and accidents on the worksites. Welfare packages are received sporadically from the Red Cross Society, the U.S. Ambassador, the Ladies Emergency League, as well as from his wife. Pay days are regular and there appears to have been the opportunity to buy and sell goods.

His diary entries regularly record the war news and rumours that were passing through the POW population. In hindsight we can recognise that much of the information that was circulating was grossly inaccurate. Germany apparently surrendered on two occasions in the course of 1916. In April 1916 Knaggs records that: ‘…five English warships are in the Sea of Marmara, and England has given Turkey 10 days to consider what she is going to do, or Constantinople will be bombarded. Great excitement in the camp.’ Knaggs records a rumour that America declared war on Germany a full year before it actually occurred.

To his credit, Knaggs caveats his later entries with: ‘rumour has it…’ and regularly commentates that some rumours just seem fanciful. But it must have been difficult for them to discern fact from rumour as other news was uncannily accurate and arrived relatively quickly after the event. For example, on April 29, 1916 the Allied forces besieged at Kut in Iraq surrendered and 8,000 soldiers were taken prisoner. The news of this event and the same figure of captives reached the camp only five weeks later on June 9 – quite possibly directly from Allied prisoners captured at Kut.

Arduous and dangerous work, poor diet and disease associated with communal living in rough conditions were all features of their experience in captivity. Unfortunately, some weren’t able to survive. On September 18, 1916, Chief Stoker Charles Varcoe died of meningitis at age 38. Meningitis is a medical condition that is caused by inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord. He was buried at the Christian Cemetery in Belemedik.

In the later part of summer in 1916, typhoid and malaria swept through the camp at Belemedik. Typhoid is a disease transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with faeces from an infected person. Typhoid is characterized by a sustained fever, profuse sweating, gastroenteritis and non-bloody diarrhoea. Malaria is an infectious disease caused by protozoan parasites and usually transmitted when bitten by an infective female Anopheles mosquito. The parasites multiply within red blood cells, causing symptoms that include symptoms of anaemia (light-headedness and shortness of breath), as well as other general symptoms such as fever, chills, nausea, flu-like illness, and, in severe cases, coma, and death.

On October 9, 1916, Petty Officer Stephen Gilbert died of malaria and typhoid at age 39. On October 22, 1916, Able Seaman Albert Knaggs died of malaria and typhoid at age 34. Knaggs’ diary entries end three months earlier on July 18 which might indicate that he suffered a prolonged illness. Both Gilbert and Knaggs were also buried at the Christian Cemetery in Belemedik.

Stoker Michael Williams died on September 29, 1916. The exact cause of his death is not known, but it is recorded that he was buried in Pozanti, likely because there was a hospital there where he may have received treatment.

Many POWs at Belemedik contracted malaria and after captivity suffered from it for the rest of their lives. Many others also suffered disfiguring injuries, but despite the hardships it would also seem that life in captivity at Belemedik became routine. In 1917, six of the HMAS AE2 crew members were relocated to another POW camp at San Stefano. In mid-1918 the construction work at Belemedik was completed and the railway opened. A photo of Australian and British POWs taken in 1918 shows them in good physical condition, well dressed, in good spirits, and apparently living in a reasonable standard of quarters complete with picket fence and chickens.

Following the Armistice, after three and half years in captivity, the remaining 28 crew members of HMAS AE2 were repatriated in December 1918. The photo below is typically associated with the crew’s capture in 1915, but given the clothing, the number of beards and moustaches, and most tellingly, the fact that there are only 28 men in the photo, it is more likely that this photo was taken in late 1918 as the crew managed to reunite, likely in London, while they were on their way home.

After the war, the Imperial War Graves Commission considered that it was impractical to look after the many isolated graves of British and Commonwealth servicemen buried in several locations across Turkey, so their remains were disinterred and reburied in selected cemeteries. One of those selected cemeteries was in Baghdad.

In 1922, Gilbert’s, Varcoe’s and Knaggs’ remains were reburied in the Baghdad North Gate War Cemetery where they remain to this day. For reasons unknown, Stoker Michael Williams was not reinterred in Baghdad, but he is listed on the Pozanti memorial in the Baghdad North Gate War Cemetery.

Eighty seven years later I came across the graves of these three brave sailors who had endured so much hardship and made the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of our nation. On behalf of all Australians I thanked them for their service.

Contact Military Historical Society of Australia - Victorian Branch about this article.