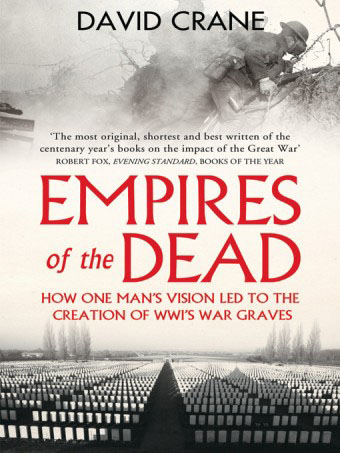

No tour of the battlefields of the two World Wars can omit a visit to at least one Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) cemetery. Indeed, with the land being returned to its original uses and being developed, these battlefields are increasingly identified through these cemeteries. The rows of uniform white headstones are at once beautiful yet tragic and represent a tangible legacy of war. The story of how they came into existence is told in Empires of the Dead: How one man’s vision led to the creation of WWI’s war graves.

Before World War I (WWI), little provision was made for the burial of the war dead. Soldiers were often unceremoniously dumped in a mass grave; officers shipped home to be buried in local cemeteries. The great cemeteries of WWI came about as a result of the efforts of one inspired visionary. In 1914, Fabian Ware, at 45, was too old to enlist. Instead, he joined the Red Cross, working on the front line in France. There he was horrified by the ignominious end to the lives of many of the soldiers who, buried hastily, were often lost as the battle lines moved backward and forward over the same ground. He recorded their identity and the position of their graves, and his work was quickly officially recognised, with a Graves Registration Commission being set up. As reports of their work became public, the Commission was flooded with letters from grieving relatives around the world.

The subsequent story of how and why this graves registration work led to the creation of thousands of cemeteries around the world and the CWGC is one of imperialism, faith, grief, guilt, ego, vision, bureaucracy, politics and resources. The story is meticulously researched and well told in Empires of the Dead. And while the end result is simple in concept and physically elegant, the process was far less so. The decision to not allow relatives to repatriate the bodies of relatives back to their homelands – particularly Britain for example – was particularly hard fought and acrimonious; as was the decision for all ranks to receive the same style of headstone.

Interestingly, the Germans followed suit by also establishing cemeteries in France and Belgium – albeit with a distinctly different style and character. Conversely, the French, with dramatically greater losses than the British Empire in WWI, allowed bodies to be returned to families and buried in local cemeteries. Significantly for Australians are some references to the challenges of identifying bodies on the Gallipoli Peninsula four years after the withdrawal.

Having established a standard it was perhaps not surprising that those Allied soldiers killed during WW2 were similarly interred. But it also is worth recognising that since then most soldiers’ bodies have been repatriated back to their homelands. In the end, the thousands of CWGC cemeteries and memorials are a monument to the sacrifice made by the British Empire during these two major wars. It is here that Crane perhaps derived the title for this book. It is somewhat ironic, however, that despite the high price paid, the British Empire collapsed as a result of these wars.

Empires of the Dead includes a few maps and a good number of colour and black and white illustrations. The notes are comprehensive reflecting the significant amount of research Crane undertook. There is also a select bibliography and an index. The RRP represents good value for money.

Coming at the start of the WWI Centenary, Empires of the Dead risks being lost in the rush and perhaps it may have been more fitting to publish it in a few years’ time. Nevertheless, it is a fascinating story that deserved to be told.

William Collins: London; 2014; 304 pp.; ISBN 9780007456680; RRP $19.99 (paperback)

Contact Marcus Fielding about this article.