To an audience of around 30, Dr McLeod stated that among the many military histories written about World War II, the Australian Army’s field ambulance men have seldom been mentioned.

This is certainly the case with those in the Papuan Campaign of 1942 – 1943: Kokoda – Milne Bay – The Beachhead Battles where they suffered the same depredations as all the soldiers. This meant that at no time during that campaign were Australian soldiers accompanied by fully equipped, fully supported, full-strength field ambulance units. The ability to render optimum treatment was compromised by many factors including logistics, priorities, leadership, the nature of the campaign itself and that the medical men were as sick as everyone else. Dr McLeod believed that the challenges they faced were largely preventable.

Although geographically close to mainland Australia, these unarmed medical men and the casualties in their care were effectively isolated in Papua. Those to the north of the Owen Stanley Range suffered more than those to the south.

Dr McLeod first became interested in the subject when her father presented her with a milk crate of documents that had belonged to her great uncle, Private Nick Kennedy, a nurse orderly from May 1940 to August 1945. In that crate was his diary documenting his time in the2/4th Field Ambulance. Nick Kennedy’s diary was both thorough and revealing and provided the jumping off point for her research.

The popular attitude at the time was that the medical problems experienced by the Australian soldiers in Papua New Guinea were inevitable. Kennedy’s view, supported by further research by Dr McLeod, was that the problems were far from inevitable and that much unnecessary suffering and death was caused by avoidable deficiencies; deficiencies caused in large part by senior leadership.

The field ambulance was set up to be a highly mobile, first treatment point for the sick and wounded before either sending them back to their units or passing them along to proper hospitals. Getting the sick and wounded to proper hospitals proved very difficult in the early stages of the war due to the difficult terrain and climate and lack of transport.

The supply and transport situation took a long time to rectify. Most of the goods and people had to come over the Owen Stanley Range by plane. Flying conditions were atrocious and it was not usual for bad weather to stop flights for days on end. Transporting battle related staff and supplies were a priority.

There were shortages of everything from critical medicines and dressings to mundane supplies. Consequently, patients were treated in dangerously primitive conditions and held, sometimes for months, in overcrowded hospital tents.

Patient evacuations were hard to organise. For some time, planes were not configured properly and berths had to be ‘bought’ from the American pilots with Japanese battle memorabilia such as Japanese helmets, swords and guns.

The situation improved somewhat after the Americans GIs joined the fight on the Beachheads. They were well supplied and were generous with what they shared with the Australians.

Local vehicle transport was non-existent outside Port Moresby. Everything including moving patients was done on foot. The field ambulance set up dressing stations as close as they could to the action to shorten travel time. This helped for immediate medical attention but without transport to Port Moresby, the sick and wounded either had to stay put or struggle over the incredibly rugged ranges on foot either under their own power or by being carried. Aid stations were set up along the route. Gravely wounded men who couldn’t make the journey often died. Certainly, the indigenous people ‘helped’ but the involvement of the so-called fuzzy-wuzzy angels has been somewhat romanticised. Most of the locals were pressed into service and behaved accordingly.

Once the men got to Port Moresby there was a long wait to be repatriated to the mainland in part because Blamey had a policy of retaining men in PNG and putting many sick men back into the fight.

The situation was particularly parlous for wounded men caught by the advancing enemy. In one incident some severely wounded men had to be left behind at Kokoda as the Australians withdrew. They were euthanised with morphine.

Medical research had suffered prior to WW2 and the army was unprepared for war in the tropics. The senior commander, Major General Burston (reputedly close to General Blamey) was bureaucratic. He and other senior officers were very slow moving. This was especially so for dealing with malaria and loss of manpower not to mention personal suffering from malaria was a huge problem. During the war, 21,000 Australians contracted the disease. Brawny men were quickly reduced to skin and bone by the affliction. Sharing the same conditions as everyone else, the ambulance men were as badly affected as all the others. Many were just skin and bone and it became a case of the sick administering to the sick.

Burston believed, as did many other officers, that malaria was a self-inflicted wound and that the men were deliberately shunning quinine. Some officers even believed that there was no point in getting the medication to the men because they wouldn’t take it. In fact, the opposite was true. The men willingly took quinine. The problem was poor supply and poor quality product when they got it. When quinine was available, wet rotten packaging frequently led to sodden unusable doses. Supply problems and obstruction also led to poor implementation of other malaria reduction measures such as installing netting, spraying with pesticides and other insect control measures.

Officers seemed to have a mania about men shirking battle by self-inflicting wounds such as shooting off the left big toe or a finger on the left hand. It was policy to return soldiers with self-inflicted wounds to their units. Private Kennedy thought that deliberate self-wounding was rare and later that became the prevailing view. Once the attitude changed, the policy of returning men to their units remained but the wound was not labelled self-inflicted unless the event was actually seen by a medical officer.

Despite having red cross markings, medical facilities sometimes came under fire. The worst instance was when Japanese Zeros strafed and bombed the 2/4th Field Ambulance Main Dressing Station at Soputa on November 1942. Of the 200 people in the station, the known casualties were 36 men killed and 77 wounded. The fatalities included the dressing station commander. The press called it a war crime. An extensive enquiry called over 500 witnesses but could not conclude that it was a war crime. This is because there was a 25 pound gun on the grounds and the station was adjacent the 7th Division HQ (located after the station was in place). It was thought that in all probability the HQ was the real target and the dressing station was collateral damage.

Dr McLeod concluded that the Australian Army’s field ambulance units in PNG did exceptional service under difficult circumstances due to the skill, innovation and tenacity of their people.

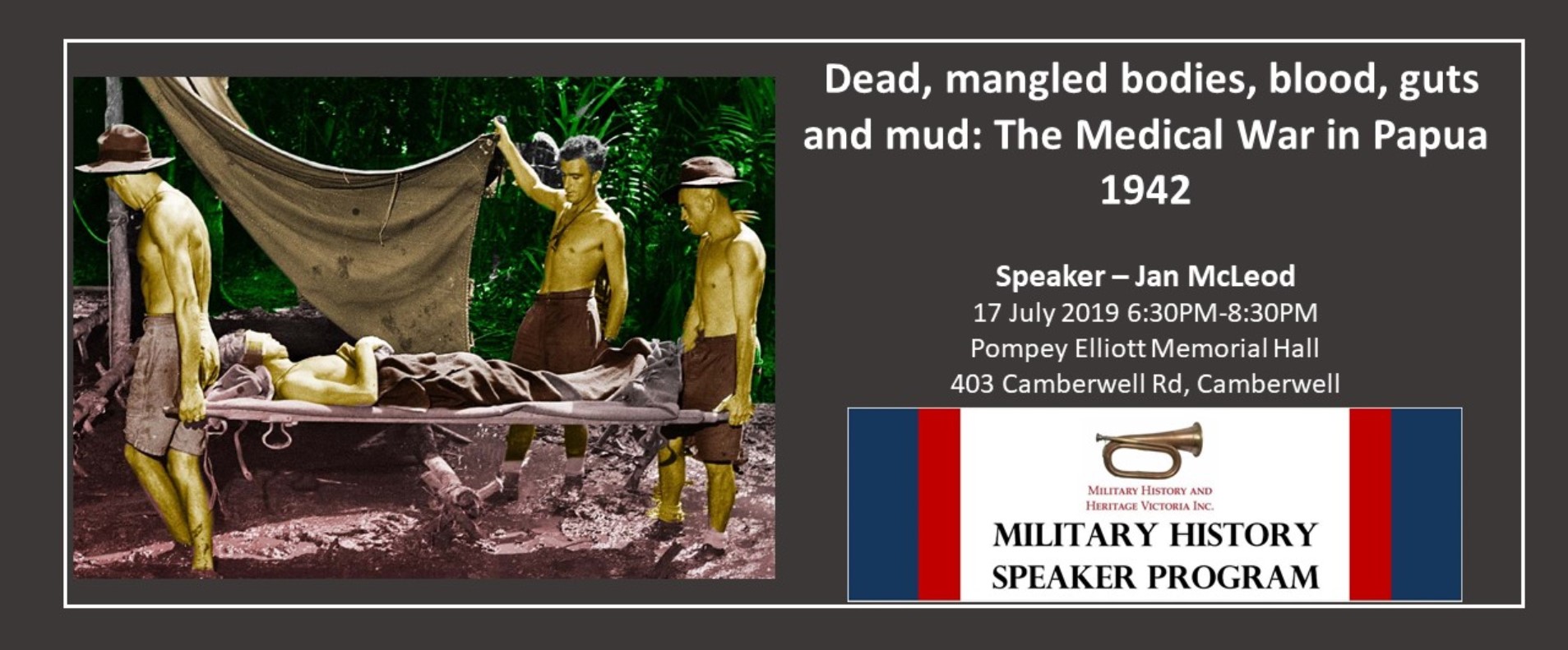

The presentation drew on Dr McLeod’s new book “Shadows on the Track: Australia’s Medical War in Papua 1942-1943” covering Kokoda, Milne Bay and the Beachhead Battles.

Copies of the book were available for sale.

About the presenter

Dr Jan McLeod

Jan is a historian, course coordinator, tutor and researcher at the University of Newcastle. Jan’s first book, Shadows on the track: Australia’s medical war in Papua 1942 – 1943 was published earlier this year by Big Sky Publishing in conjunction with the Australian Army History Unit. She has also published journal articles and reviews – and presented her research at various conferences. Her Honours thesis contrasted popular representations of medical aspects of the Papuan Campaign with experiences recorded in the personal diary kept one of two great-uncles who served in the 2/4th Australian Field Ambulance during World War Two. Jan’s PhD thesis ‘Within Reach, Beyond Care’ expanded on this research by critically examining broader aspects of the medical care of Australian soldiers during the Papuan Campaign, with a focus on the field ambulance units.

Jan has a Diploma in Secondary Education (History and English), a Bachelor of Arts (Honours), and a PhD in History. Her lifelong interest in history, health and education is reflected in her varied working life – as a student nurse, adult education tutor, secondary school teacher of History and English, road safety education trainer and area co-ordinator, and research assistant on various university projects.

Contact Brent D Taylor about this article.