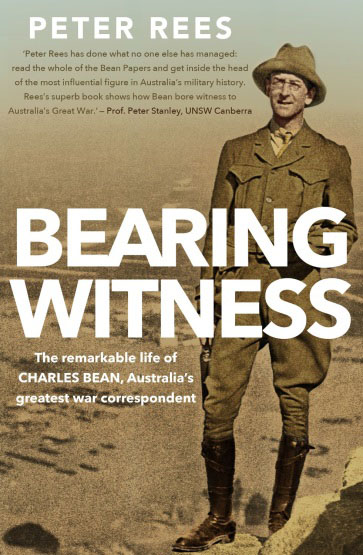

Book Review – Bearing Witness is a remarkably insightful and informative biography of C. E. W. (Charles Edwin Woodrow) Bean – arguably Australia’s most famous war correspondent and war historian. Charles Bean is the journalist who told Australia about the horrors of Gallipoli and the Western Front. He is the patriot who was central to the establishment of one of this country’s most important cultural institutions, the Australian War Memorial. He is the historian who did much to create the Anzac legend and shape the emerging Australian identity in the years after Federation.

Peter Rees has produced a tremendous portrait of Charles Bean that not only considers the man but the context of his experiences as well as the influences on his beliefs and actions. Bearing Witness is a very readable account that addresses many of the myths and controversies surrounding the man who bore witness to Australia’s participation in the Great War.

Bean’s early life seemed destined to produce one outcome, being appointed official war correspondent to the Australian Imperial Force, a role without precedent. “Since he answered to no senior commander, Bean knew that the execution of his duties would depend entirely on his judgement.” And, predictably, on censorship – the bane of all war reporters – by the British and, later, Australian commands.

In Cairo, he cast a negative eye over the Diggers’ antics in brothels and bars, noting between 200 and 300 were absent without leave. But all that changed on the morning of 25 April 1915, “a day that would fuse Charles Bean and Australian history”. From a troopship, Bean watched the soldiers landing at Gallipoli under Turkish fire, and, five hours later, waded ashore with his camera.

“I took a photo of two of the fellows landing and then turned around to see the beach.” What he saw were half-a-dozen dead Australians, wrapped in overcoats, and further away, another two-dozen bodies. The slaughter had begun; so too had Bean’s love affair with the troops. Bean wrote at the tactical level and placed soldiers and junior officers at the centre of his accounts. “The wild, pastoral independent life of Australia,” he wrote, “if it makes rather wild men, makes superb soldiers.”

A year later, he was facing German barrages in Flanders Fields – “Dead men’s legs, a shoulder, now a half buried body stick out of the tumbled red soil – bodies in all sorts of decay, some eaten away to the skull” – filing his reports, but increasingly filling his diary with uncensored entries for the role he foresaw for himself: Australia’s official war historian.

War reporting and writing war history are quite separate roles, however, and, as Rees shows, somewhere in the middle of the conflict, Bean began to conflate the two. By 1917, the war had generated media competition, which troubled Bean’s mission to record the truth. “Scoops, competition, magnification and exaggeration,” he declared, “are out of harmony with what is best for the country.”

When the guns fell silent on 11 November 1918, Bean chose not to join the celebrations but drove to Fromelles to take photos and to pick up the bones of Australian dead. Even back in London, dining with fellow war correspondent Keith Murdoch, “Bean could not bring himself to join in”.

Returning to Canberra, Bean married Effie Young, a local nurse, and set about formally recording the war on paper. By early 1929 he had completed writing the third volume of his allotted six; there would be 12 volumes in all. In 1942 the job was done: four million words and 10,000 pages of official history, to explain and emphasise Australia’s often controversial role in the Great War. As Rees notes, Bean in 1918 could not have imagined “he would be releasing his final volume when Australia went to war again”, that the very horrors he had seen and described so vividly would be recycled for a new generation.

Peter Rees has been a journalist for forty years, working as federal political correspondent for the Melbourne Sun, the West Australian and the Sunday Telegraph. He is the author of The Boy from Boree Creek: The Tim Fischer Story (2001); Tim Fischer’s Outback Heroes (2002); Killing Juanita: A True Story of Murder and Corruption (2004), which was a winner of the 2004 Ned Kelly Award for Australian crime writing; The Other Anzacs (2008), republished as Anzac Girls (2014); Desert Boys (2011); and Lancaster Men (2013).

Bearing Witness includes a number of black and white photographs, extensive end notes as well as a comprehensive bibliography and an index. In all, it is a superb read and I commend it to all.

Contact Marcus Fielding about this article.