For many, the 1977 movie A Bridge Too Far is the main point of reference for Operation Market Garden. Romanticised for the audience of the day, the film was based on Cornelius Ryan’s book of the same name (Hodder & Stoughton, 1974). As part of his research, Ryan had the opportunity to interview many of the participants, but critics felt that he was insufficiently critical in judging many of them. With the benefit of an additional 44 years’ perspective, as well as additional sources, Beevor’s account is more holistic, objective and critical.

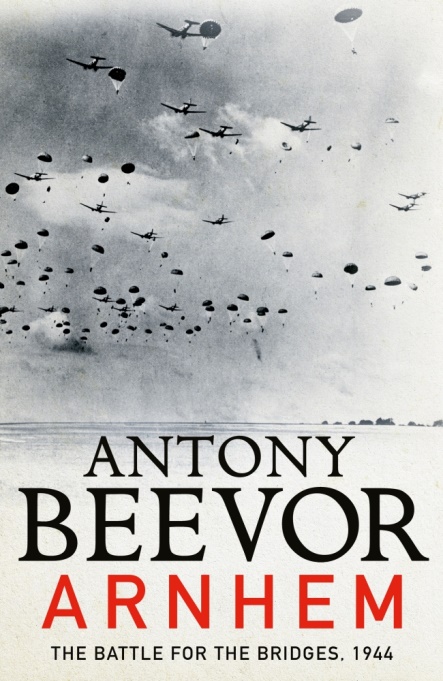

Operation Market Garden was intended to clear the road from Neerpelt in Belgium, via Eindhoven and Nijmegen to Arnhem in Holland. Success would lead to the liberation of Holland and provide a route into Germany’s industrial heartland that by-passed the well-defended Siegfried Line farther south. Three divisions of airborne forces, dropped by parachute and gliders, were to take a series of six bridges, the last over the Rhine at Arnhem (the Market component); and then to be quickly reinforced by ground units (British XXX Corps) arriving by road (the Garden component). It was a bold plan: the Americans thought it unusually bold for Montgomery.

There is still debate about whether Operation Market Garden might have shortened the war or was folly from the outset. One military maxim says that an operation’s outcome rests 75 per cent on planning and 25 per cent on luck. Even if this plan had been impeccable, it needed improbable good fortune to succeed. Beevor concludes that Operation Market Garden “ignored the old rule that no plan survives contact with the enemy”. The cost of failure was high.

Tragically, heroism and incompetence are often separated by a fine line. The British fascination with heroic failure has clouded the story of Arnhem in myths. Beevor, using often overlooked sources from Dutch, British, American, Polish and German archives, has reconstructed the terrible reality of the fighting and brings to life every aspect of the battle.

Beevor recreates the operation from the dropping of the first troops on 17 September 1944 to the evacuation of the remnants from Arnhem eight days later. In alternating chapters, he dissects the events chronologically. He separates the actions of the two United States airborne divisions (101st at Eindhoven; 82nd at Nijmegen) and the British 1st Airborne Division and the Polish Brigade at Arnhem from the ground component (British XXX Corps). At times, however, the wealth of detail threatens to confuse the reader; but the complex interplay of so many actors and degrees of confusion are characteristic of war.

The misjudgements of egotistical commanders are exposed by their own actions and words. How much Montgomery was motivated by personal rivalries is disputed, but there is no doubt he saw Operation Market Garden as an alternative to Dwight Eisenhower’s “broad front” strategy, which he despised. Eisenhower acceded to his relentless demands for resources, including American airborne divisions and vast numbers of transport aircraft. In the battle of the post-war memoirs, however, Montgomery still blamed failure on Eisenhower’s parsimony.

The reasons for the disaster that befell the airborne assault were many and various. Montgomery discounted intelligence from the Dutch resistance that warned of a large German build-up around Arnhem. British tanks arrived too late to help; they had to come by a narrow road which ran across marshy polder land and was highly vulnerable to German attack. The decision to spread the troop drops over three days (because of shortening daylight) forfeited tactical surprise, as did the drop zones’ distance from the objectives (the zones were initially chosen to avoid enemy flak). German fighting spirit had not collapsed after defeat in Normandy, as had been supposed, and the German response to the landings was swift and effective.

The experiences of individual soldiers both appal and inspire. Five were awarded Victoria Crosses, four of them posthumously.

Operation Market Garden was not a complete failure; part of the southern Netherlands was liberated and five of the six bridges, though not the key one at Arnhem, were held. But Allied casualties numbered around 17,000 and thousands more were taken prisoner. German reprisals against the Dutch were pitiless and cruel, and led to a famine that killed over 20,000.

Beevor was educated at Winchester and Sandhurst, where he studied under John Keegan. A regular officer with the 11th Hussars, he left the Army to write. He has published four novels and ten books of non-fiction including Stalingrad (Viking, 1998) and Berlin: The Downfall 1945 (Viking, 2002). Altogether, more than five million copies of his books have been sold.

Arnhem includes 51 black-and-white images, 11 clear maps, one three-dimensional drawing of the terrain around the Arnhem bridge, notes, a bibliography and an index. There is also a key to the military symbols used in the maps, a table of military ranks and a glossary.

In Arnhem, Beevor tells a complex story well. His assessments are informed and balanced. It is highly recommended to all students of military history.

Contact Marcus Fielding about this article.