Many museums have an item or two in their collection that almost every other similar museum keeps. It could be a helmet, a rifle, a tunic, a book or any one of possibly thousands of different artifacts. These items are often put away in a safe place and forgotten. They are very usually of little interest. That is until someone finds it again and their interest is sparked to learn more.

Recently I went searching our museum archive and library database for a much needed book. The computer gave me all the information it had. Yes, we had the book, but sadly the database was incomplete and the location of the book was unfortunately missing. I’ve spent enough time in this library to know where it should be. So I headed for the shelves.

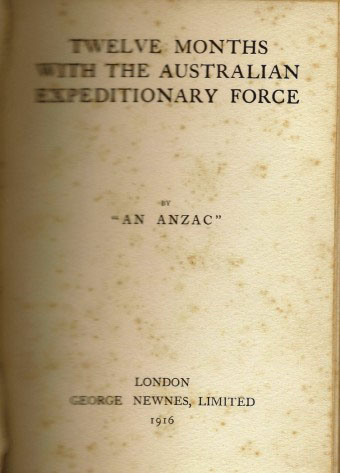

It’s very easy to be taken off task when each book spine you read sounds fascinating. During this search I found myself distracted by many books and documents, but two from different locations spiked my interest. One, small dark blue book titled Twelve Months with the Australian Expeditionary Force intrigued me. This small and simple looking book claims to have been written in 1916 by “An ANZAC”. The book itself, and indeed its contents, are of very little interest. However the mystery of the unknown author became my distraction of the day.

My first internet search indicated that the book existed in many libraries around Australia and even a few overseas. The Australian War Memorial has a copy. The National Library of Australia lists a number of libraries around the nation where a copy can be found. Also Dakota Wesleyan University in the United States of America has the book. Indeed, DWU even have a downloadable sample of Twelve Months with the Australian Expeditionary Force on their website.

George Newnes Ltd published the book almost a century ago in 1916. Despite being the publisher of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes novels, Newnes publishing is no longer contactable to help identify “AN ANZAC”. Perhaps this common little book is one of those items that many libraries and museums have, but very few people actually get to see. After all, something so common is easy to overlook.

The Preface to “An ANZAC” gives the reader his reason for this short (110 page) account of his time at ANZAC Cove and other parts of the peninsula: “Lying in bed in hospital, I have just finished reading an article written by a man who has two hours on the Gallipoli Peninsula, and if an account of two hours’ work made an interesting article, then I claim that having been on the Peninsula for seventeen weeks with the First Division, in a battalion that was in every important engagement that took place on the Peninsula, my own story should be of interest to the British public.” In his opinion the campaign was a success due to keeping the Turks occupied, and the subsequent high enemy casualties “easily three times as many men as we have lost”.

As a brief account of the Gallipoli campaign the book is a product of its time. He writes with pride about his colleagues and leaders, as well as using language to describe the Egyptians that we no longer find acceptable. He shares many experiences and anecdotes of historical elements of the campaign that the reader may find familiar. His account of the discovery of a spy seems fanciful but intriguing at the same time. In his opinion a SGT J. S. Duffey should have won a V.C. for rescuing two men under fire and against orders. He felt certain that an Army Medical Corps man (whose name escaped him) was going to be “Our first V.C.” This AMC man took water and provisions to the firing line, and would bring the wounded back on his small donkey. The donkey was found alone one day munching on some grass. The body of the AMC man, whom we know now to be John Simpson Kirkpatrick, was found a few metres away down a gully. The account contains all the well-known battles including Lone Pine, and the subsequent temporary truce with the “Turks” to bury the bodies. Generally speaking this small book is an easy-to-read account of those few months at ANZAC Cove.

The first clue in the book that seems worth following is his claim to have left Port Melbourne at 9am October 19th, 1914 on the “Benalla’ as part of the 8th Battalion. More searching at the Australian War Memorial would find for me the names of those from the 8th who boarded the “Benalla”. The challenge would then be to troll the National Archives for every service record that made the list looking for a soldier who fits the narrative of the book.

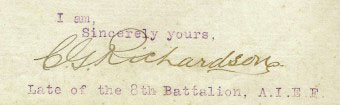

One soldier does. 846 Private Cyril George Richardson of the 8th Battalion fits the description right down to the injury that sends him to Lewisham Military Hospital. In the book “An ANZAC” refers to a groin injury. In Private Richardson’s service record it states the injury to be a little more “serious” but in the right region. Around the time of the book’s publication, Private Richardson was being sent home from the Western Front suffering from Shell Shock. His story seems to end there. Further searching of public records from the era tells us little more about C.G. Richardson than is already available in his service record. Perhaps he, like so many others, never recovered from the horrors of war.

Everything points to 846 Private Cyril George Richardson. But to be honest I already knew it was him when I started my information search about the book. In such a diverse collection as the Fort Queenscliff Museum Library there are many of these forgotten items. When I found Twelve Months with the Australian Expeditionary Force I was searching for something else. The book’s title jumped out at me because previously in my search I had found a typed manuscript with the same title on another shelf. The manuscript, it turned out, is identical to the book except for the signature of C. G. Richardson, late of the 8th Battalion AIEF.

So now we know who “An ANZAC” is but the mystery continues. How did the manuscript and the book find its way to our library? And what other moments of history are hidden in other museums and collections?

By the way, the book I was originally searching for was sitting on a single shelf directly behind the computer that I used to seek its whereabouts. If I had looked on those shelves first I would never have been distracted.

Sometimes you just get lucky.

Contact Jason McGregor about this article.