After four months of bitter fighting since invading the Italian mainland, by the end of 1943 the combined British and American armies hadn’t got much to show for it.

Certainly they had forced political change, replacing the Fascist dictatorship of Mussolini with a new government that withdrew from the military alliance with Nazi Germany and surrendered such of their armed forces that remained under their control. The Italian fleet based at Taranto had hoisted the black flag of surrender and sailed to Malta, Gibraltar and other Allied ports, thus removing the naval threat in the Mediterranean.

After a painstaking advance from the toe of Italy by the British 8th Army, for which Montgomery was severely criticised by both American and British commanders, the strategic port of Naples had finally been captured but left largely inoperable due to widespread sinkings which had choked the harbour, and German demolitions. The push further north had become stalled and severe winter weather had set in, delaying still further any prospects of an early capture of Rome.

During their retreat, the Germans had conducted a skilful withdrawal, destroying bridges, ripping up railway lines and demolishing tunnels, leaving a trail of havoc in their wake. They had also kept their forces largely intact and not suffered any severe losses in either men or equipment. By comparison, the capture of Naples had resulted in severe Allied casualties and produced an ever lengthening supply line that was barely able to maintain any further advance.

After abandoning the so-called ‘Barbara Line’ between the river Trigno and the village of San Pietro in which a mere 100 Panzergrenadiers caused 1500 American casualties, the Germans had withdrawn to a second series of fortifications know as the ‘Gustav Line’ which stretched across the entire breadth of the Italian peninsular from south of Ortona on the east coast to Gaeta on the west coast. This defensive line was anchored on the massif of Monte Cassino with its 700 year old Benedictine monastery dominating the surrounding area. And it was here on the rocky, unforgiving slopes of Monte Cassino where things really ground to a halt and developed into one of the great land battles of the war.

Interestingly, on 22nd November, having established a bridgehead of five infantry battalions of 8th Army on the north bank of the Sangro river, Montgomery had prematurely declared that ‘the road to Rome was open’. This was pure Monty hyperbole and had no relation to the actual situation facing the Allied forces in their attempt to capture Rome. In any case, Montgomery was about to leave Italy to prepare for the invasion of France, much to the relief of his many critics who claimed he had been over cautious and failed to exploit favourable opportunities.

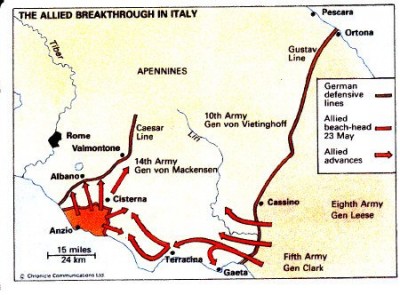

In an attempt to outflank the ‘Gustav Line’, on 22nd January 1944 Allied forces mounted a second sea-borne invasion behind enemy lines at Anzio on the Tyrrhenian Sea. The Germans were caught entirely by surprise and by the first evening 50,000 troops and 3,000 vehicles were ashore against negligible opposition. The road to Rome, barely 51 kilometres away, really did seem to be open. But once again initial success proved to be illusory and the force commander, U S Major-General John Lucas, failed to grasp the opportunity to push ahead, with strong mobile forces giving the Germans sufficient time to bring up reinforcements.

Indeed, far from breaking out and pushing on to Rome, by the middle of February and under constant German attacks, the new beach-head was on the defensive and being pushed back towards the sea, even raising the prospect of another Dunkirk-type evacuation. Churchill was furious at this latest setback to break the deadlock at Cassino growling: ‘We hurled a wildcat on the shores of Anzio – all we have is a stranded whale!’ which did not exactly improve relations between the Allied force commanders already under considerable strain about the conduct of operations.

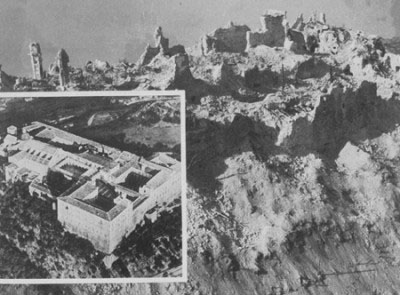

As if this was not bad enough, the Allies now committed one of the most stupid blunders of the entire campaign. Believing that the Germans were using the Cassino monastery as an artillery observation post and frustrated at not being able to make any progress to capture it by ground forces, they asked the American Air Force to launch a massive bombing raid which reduced the mighty edifice to a shattered ruin – 600 tons of bombs were dropped in 20 minutes by B17s and medium bombers. The result was a military disaster which delayed any progress towards Rome for four months.

As it turned, out the monastery was not occupied by the Germans and never had been although some had been there to help the monks remove the precious books and manuscripts for safekeeping in the Vatican. But this did not amount to any military occupation of the building. In fact, they had been given strict orders not to occupy the monastery.

Realising that the wrecked monastery now provided perfect defensive positions, including hiding tanks behind piles of rubble, they now set about fortifying the ruins in earnest, deploying battle-hardened paratroopers who had unrestricted fields of fire across the entire Liri valley below. The result was that when the New Zealanders and the 4th Indian Division began their assault following the aerial bombardment, they were repulsed with heavy losses. And this was to be the pattern over the next few months, with attacks by a whole range of Allied forces – Poles, Free-French, Canadian as well as British and American – without achieving any appreciable result. Every yard, every rocky crevice, every pile of masonry was bitterly contested and casualties were mounted alarmingly. Stalemate had become slaughter, Cassino a killing field.

Adding to the Allies woes, the Luftwaffe, which had been notably absent in the fighting so far except in attacking the Salerno landings in the first three days when they mounted 550 sorties, began mounting a series of damaging attacks, particularly against Allied

shipping which was supporting the invasion. Operating from airfields in northern Italy and using a new type of ‘glider-bomb’ – the first air-to-sea missile of its time which was mounted under the wings of a Dornier 217-K3 bomber – they attacked and sank the British hospital ship ‘St.David’, the destroyer ‘Janus’, damaged her sister ship ‘Jervis’ and also sank the cruiser ‘Spartan’, together with four transports, all within a few days. The German navy also contributed to disrupting Allied shipping, a U boat sinking the Royal Navy light cruiser ‘Penelope’. The campaign in Italy was by no means going well either on land or at sea, and the air forces had managed to create an even greater stumbling block at Cassino. It appeared that Hitler’s policy of tying up as much Allied military effort in Italy for as long as possible in order to delay the expected channel invasion of France was paying off. What was to be done?

As the rain and snow teemed down on the frustrated Allied troops before Cassino, a major question mark now hung over the whole future of the Italian campaign.

In an effort to produce a cohesive strategy that would break the deadlock, a plan known as ‘Operation Diadem’ was devised whereby the British 8th Army would be brought from the Adriatic front to combine with the US Army in a full-scale attack timed to synchronise with a break-out from the beach-head at Anzio. This, it was hoped, would bring about the capture of Rome and a quick end to the Italian campaign.

It should be explained that at this stage the planned Allied invasion of Normandy, ‘Operation Overlord’, was due to take place in May the next year, not on the 6th June as actually occurred, with a diversionary landing in the south of France near Marseilles –‘Operation Anvil’, timed to take place three weeks beforehand with the aim of drawing off German divisions from France. The British were enthusiastic about the plan, as was Churchill, determined to achieve what he saw as a ‘British’ victory in Italy.

But the Americans were opposed, concerned about growing losses in Italy and the generally slow pace of the campaign, and favoured the ‘Anvil’ operation as more acceptable, and lengthy cables were exchanged between London and Washington in efforts to resolve the matter. In the event, the Americans led the invasion of southern France some three weeks after the Normandy landings had taken place in which this writer took part.

The appalling weather continued to hamper operations at Monte Cassino but in early March the rain and low cloud cleared sufficiently at Anzio to allow bombers to blast the Germans attacking the beach head, forcing Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, the German Mediterranean Commander-in Chief, to call off the offensive much to Hitler’s fury. He had demanded that the beach-head ‘be crushed in the blood of British soldiers’.

On 15th March, the Allies mounted yet a third attempt to capture the town of Cassino and the historic monastery that towered on the heights above and penetrate the ‘Gustav Line’. Once again it was preceded by a massive bombing attack that flattened the town, one estimate putting five tons of bombs being dropped for each defending German soldier, such was the determination to try and break the deadlock. But once again when the New Zealand 6th Infantry Brigade went in they came under intense enemy fire and were driven back. However, the Gurkha’s, who had joined the assault, had more success and by sheer guts and determination managed to climb to a point known as ‘Hangman’s Hill’ only 440 yards from the monastery or what was left of it.

Eight days later the attack was called off. It seemed that nothing could or would dislodge the intrepid defenders who, by now, had earned the grudging respect of their adversaries. Allied losses in this latest attempt had again been severe. The New Zealanders incurred 863 casualties while the 4th Indian Division, which included the Gurkha’s, lost over a thousand. A high price indeed without any tangible result.

It was not until May 13th that General Alexander, now Commander in Chief of all Allied forces in Italy, General Eisenhower having been appointed supreme commander of the coming invasion of France, felt sufficiently prepared to launch yet another attack to breach the ‘Gustav Line’ and capture Monte Cassino. Intensive planning had gone into this operation, the British 8th Army being regrouped alongside the American 5th Army as mentioned, under cover of darkness and under huge smokescreens. It began with a bombardment from 1600 heavy guns and hundreds of tanks supported by 3,000 aircraft.

Although the defending German paratroopers as always stood their ground and fought tenaciously, the sheer weight and numbers of the attackers overwhelmed them and forced the survivors to withdraw. As the assault swept ever forward, it was troops of the Polish II Corps that finally hoisted the flag over the ruined monastery while British troops occupied what was left of the town of Cassino and American and Canadian troops advanced in strength along the Liri valley. With the bastion of Cassino finally captured the Gustav Line now began to disintegrate and the road to Rome really did seem to be open.

But securing the great political prize of liberating the first enemy capital of the war was not as easy as it seemed, the German army conducting a systematic withdrawal to new defensive positions – the Caesar Line – after putting up fierce resistance at Cisterna in which 950 men of the US 3rd Division were killed or wounded. Similarly, an attempt to outflank the retreating German Tenth Army by US forces on the vital road junction at Valmontone north-east of Rome was stopped almost immediately by a rearguard of German tanks and anti-tank guns.

The question was would Rome have to be fought over and bombed and ruined like Naples had been or would the Germans withdraw? Earlier the Allies had declared Rome an ‘Open City’. Would the Nazi’s respect the historical and religious significance of the Eternal City? Or would the insanity of destroying every Italian town and city continue?

Brian Burton. COPYRIGHT (All rights reserved)

Contact Brian Burton about this article.