Operations.

Part 1 of this two-part series examined the lead-up to Operation Oboe 1, the Australian landing on Tarakan on May 1st 1945. It described how Oboe 1 was intended to form a crucial part the overall Borneo campaign plan; the personality clashes and command problems in the RAAF’s high command; the long delay in making the Tarakan airstrip ready for operations; and, the subsequent condemnation of the operation by historians. Part 2 examines the operation itself.

The RAAF and the Tarakan Landing

So how did the RAAF perform during the opening phase of Oboe 1? In short, there were plenty of problems.

As the assault convoy sailed from Morotai to Tarakan, First TAF struggled to provide continuous air cover. According to the official history, it was ‘evident that the Australian pilots engaged in convoy escort had been given insufficient briefing.’[1] Fortunately, the Japanese air force did not put in an appearance, and when the US Thirteenth Air Force took over as planned, the provision of air cover went smoothly as the convoy approached Tarakan.

During the operation there were still more glitches. Bostock reported that the unloading of RAAF stores was difficult because the ‘tactical loading of ships, though well planned was badly executed. Beach control at the far shore was inadequately organised. Some communications equipment was unequal to the tasks required of it and breaches of close air support procedures occurred.’[2] The Army was also critical of what it considered to be the poor discipline of RAAF personnel. With the airfield non-operational for several weeks, many airmen in the beachhead had little to do. It is not surprising that this led to problems, such as the looting of abandoned houses. The air force’s somewhat tarnished reputation was retrieved to a degree, however, when the previously unemployed airmen did good work unloading stores.[3]

RAAF historian Gary Waters noted in his study of Oboe air operations that ‘there was almost a casualness to RAAF planning for Oboe One.’[4] Perhaps this was another reason why Bostock wanted to get rid of Cobby. Certainly, Morshead agreed that Cobby should be removed.[5]

But the problems did not end there. On May 1st as MacArthur, Bostock and other senior officers watched the landing from a warship, only American aircraft could be seen pounding the island, even though RAAF squadrons were slated to be included. As historian Mark Johnston explained in his book Whispering Death, ‘Bostock was intensely embarrassed, and soon learned the reason: while the fleet was sailing, and radio silence was in force, his nemesis Jones had sent a message to RAAF squadrons telling them they were grounded as they had completed their allotted monthly flying hours!’[6] This fiasco was probably the worst example of the poisonous Jones-Bostock feud directly affecting operations.

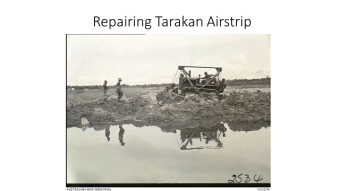

Tarakan Airstrip

The problems just outlined were secondary, however, to the overriding problem of repairing Tarakan airstrip. This task occupied the two RAAF airfield construction squadrons for seven weeks before the strip became operational. Even then its capacity was limited and it needed continual repair for as long as it remained an Allied base.

The strip had been bombed heavily and severely cratered – more than it needed to be – by the preparatory air bombardment. Not attacking it at all would have disclosed the objective, but turning it into a quagmire only served to hinder the Allied cause.

The RAAF’s reports of the strip’s repair alternate between despondent chronicle and optimistic prediction negated day-after-day by the appalling challenge the engineers faced. Before the heavy construction equipment could move in, mines and booby traps had to be cleared. In two days a RAAF bomb disposal unit found and defused 114 mines.[7]

Then came the task of filling in the water-logged craters. Increasingly desperate RAAF construction men filled them with timber, pipes, concrete, steel mesh, and boiler plate, all of which gradually settled into the ooze. Indeed, it was later claimed that the fill included a bulldozer that sank so far into the muck that it could not be extricated. Eventually, the craters and boggy patches were filled with hundreds of 44-gallon drums packed with mud.

To the RAAF’s chagrin, Army sappers had to be called in to help and local Indonesian labourers were also put to work on the strip. The Netherlands Indies Civil Affairs Unit provided 200 workers on May 11th, 240 on May 15th, and 400 on May 19th.[8] Once the craters were filled and the ground levelled, the engineers then had to lay miles of perforated steel Marsden matting. This was needed to provide a surface firm enough to take weight of aircraft.

In addition to the massive repair task, the rehabilitation of the strip was held up by bad weather. A history of RAAF airfield construction squadrons noted that at Tarakan there was ‘perpetual competition between water and men’. Bomb craters once pumped out, refilled with overnight rain and ground seepage with one airman noting in his diary that ‘machines were bogged everywhere.’[9] On June 6th it was estimated that only four days without rain were needed to allow the completion of the strip. But to the bitter frustration of those labouring in the mud, there were only two rainless days from 6th to 25th of June.[10] On June 15th, just as the strip dried from the previous week’s downpours, 132 points (33 millimetres) of rain fell. By June 21st the routes alongside the strip were so ruined by graders and bulldozers that drivers were allowed to drive over Marsden matting, causing subsidence and corrugations which in turn needed more repairs.[11] As Odgers observed, the continued wet weather ‘had a depressing effect on the spirits of many of the men and they began to despair of ever completing the job.’[12]

The Japanese also did their best to slow the work. Hardly a night passed without infiltrators attempting to breach the perimeter. On the night of May 31st, for example, a large party of Japanese attempted to sneak through the Australian lines. During the resulting fight, a grenade killed a RAAF sergeant and wounded another, while the airfield construction engineers killed four Japanese. Work continued under floodlights throughout the night, in spite of the interruptions.[13]

Tarakan airfield finally received its first aircraft (aside from a handful of Auster light observation planes) on June 28th – and operations began on June 30th – seven weeks later than planned. Nevertheless, the diarist of 1 Airfield Construction Squadron wrote that the event ‘caused a great uplift in spirits and to a man members showed great pleasure and pride in having at last mastered the weather and the conditions.’[14]

Unfortunately, the strip remained too rough to handle the large twin-engine Beaufighters and it could be used only by single-engine aircraft: the Kittyhawks and Spitfires of 78 (Fighter) Wing. Even then, the strip was perilous for the fighter pilots. Flying Officer Neville MacNamara (later Air Chief Marshal Sir Neville) recalled the common folklore about the strip that ‘it was one of the few airfields in the world where one end rose and fell with the tide.’[15]

Planning Problems

The air commanders’ lack of knowledge of the appalling state of the airfield was a major failure. In the weeks leading up to the landing, photographic reconnaissance and intelligence reports clearly indicated that the strip had been badly damaged by Allied bombing and the craters were filling with water. Despite this, the pounding of the island by American and Australian bombers continued. To quote Peter Stanley in his book Tarakan: An Australian Tragedy, the air commanders ‘simultaneously planned the complete destruction of the airfield which they not only wished to use, but which formed the basis of the entire operation.’[16] Thus when Scherger took over First TAF on May 10th, it was immediately apparent to him that ‘a satisfactory strip could never be constructed.’[17]

Nevertheless, as mentioned, air operations began from Tarakan on June 30th – just one day before the Balikpapan landing. As the air planners could not be sure when Tarakan would become operational, initial air cover for Balikpapan was provided by American P-38 Lightenings operating at extreme range from the Southern Philippines. Three US Navy escort carriers were also used in case bad weather prevented the Lightenings from reaching the target. The Americans also provided most of the heavy bomber support during the landing.

RAAF Operations from Tarakan

So once Tarakan airstrip opened, and operations were finally underway, what did the RAAF achieve? 78 (Fighter) Wing began flying combat missions from the strip on June 30th. Despite the difficult flying conditions, the wing mounted a significant effort in support of the Balikpapan landing and the continuing operations in North Borneo.

During July the four squadrons of the wing (75, 78, and 80 Kittyhawk Squadrons and 452 Sptifire Squadron) flew 858 operational sorties, during which they: dropped over 239,000 pounds of bombs and expended more than 337,000 rounds of ammunition. As a result, 78 Wing claimed to have destroyed or damaged 76 buildings and huts, seven watercraft, fourteen vehicles, twelve fuel and ammunition dumps, two bridges and a railway engine.[18] 452 Squadron also shot down a Japanese bomber over Balikpapan – probably a Nakajima Helen.[19]

The cost was the loss of three Kittyhawks and three Spitfires, with one pilot killed, one missing believed killed, two missing, and two who were uninjured following successful parachute descents.[20]

78 Wing’s operations included providing close air support to the 7th Division at Balikpapan. The wing’s official record underscored the success of these operations by quoting a congratulatory message from the 7th Division:

Strikes by fighters this area over past three days highly successful. Bombing strafing excellent. Army personnel elated with support. Congratulations to aircrew ground staff responsible these actions.[21]

Another focus of operations from Tarakan were airstrikes against Japanese troop concentrations in north-eastern Borneo, including around Sandakan and Tawao. It appears that these strikes were, at least in part, to support the guerrilla operations co-ordinated and led by Z Special Force parties. As 78 Wing noted, the aim was to keep Japanese units on the move, preventing them from gathering food supplies, ‘and driving him into the jungle where friendly Dayaks could inflict casualties.’[22]

In a letter dated July 7th to the Army Minister, Frank Forde, the Australian Commander-in-Chief, General Sir Thomas Blamey, noted that while the capture of Tarakan and Brunei Bay had gone ahead successfully, the capture of Jesselton and Sandakan still lay ahead and there were ‘considerable enemy forces‘ around those areas.[23] So if the war had gone on as Blamey – and MacArthur – expected, 78 Wing at Tarakan airfield would probably have continued to provide air support over northern Borneo, even after the end of the Balikpapan operation.

For the first half of July, 78 Wing supported the 7th Division directly from Tarakan. The plan was to open a fighter strip on 7 July at Sepinggang, five kilometres along the coast from the Balikpapan beaches. But due mainly to the state of the road leading to the airfield, it did not become operational until July 15th.[24] From then on 78 Wing aircraft from Tarakan staged through Sepinggang allowing them to spend much more time over the battlefield and to respond to requests for air support at very short notice. It also allowed the wing’s Kittyhawks and Spitfires to range as far as Banjermasin, 320 kilometres south of Balikpapan, and to cover American PT boat operations along the west coast of Celebes. These operations involved round trips from Tarakan of up to 1,800 kilometres.[25] So in contradiction to the official history’s assessment, the RAAF clearly did use Tarakan for strikes ‘against other points in the Netherlands East Indies’, although not on the scale intended.

As mentioned, the delay in opening Tarakan airfield caused despair among the RAAF engineers who struggled to repair it. During the second half of May and through June morale in 78 Wing was also in a slump while its pilots waited impatiently on Morotai. The Operations Record Book of 80 Squadron noted that during May the ‘morale of the whole squadron is lower than ever before, due to the continued inactivity’.[26] But once Tarakan airfield became operational at the end of June, morale rose accordingly. On June 30th the Operations Record Book of 452 Squadron hit an optimistic note: ‘all personnel are pleased to see our aircraft once more engaged against the enemy, all look to the future with keen anticipation.’ By July 19th, after nearly three weeks of intense operations from Tarakan and Balikpapan, the squadron believed it was engaged in ‘the most effective operations against the enemy in two years’ and that its pilots ‘thoroughly enjoyed’ barge sweeps among the waterways and rivers around Balikpapan.[27]

Conclusion

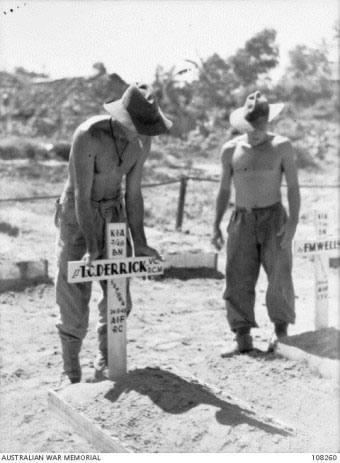

From an army perspective, Oboe 1 resulted in bitter fighting and heavy casualties. As Gavin Long observed, ‘Another reason why, in retrospect, the choice of Tarakan as an objective seems unfortunate is that it was an island from which the defenders had no means of withdrawal, and since they would not surrender, they sold their lives dearly.’[28] The result was that the 26th Brigade Group’s casualties on Tarakan – 225 killed and 669 wounded – were about the same as those suffered by the 7th Division at Balikpapan. The 7th Division – a force nearly three times the size of the 26th Brigade Group – lost 229 killed and 634 wounded. Tarakan’s casualties included outstanding veterans such as Lieutenant Tom ‘Diver’ Derrick VC, who died of wounds from a burst of machine gun fire during one of the many fights for the hills beyond the airstrip. This was a high price to pay for an airfield with that did not meet the planners’ full expectations.

The Grave of Lieutenant Tom ‘Diver’ Derrick VC

For the RAAF, Tarakan remained a deeply flawed operation. It threw the RAAF’s internal divisions into sharp relief, and it revealed a number of problems with basic operational procedures from the poor loading of landing ships to the inability to provide continuous air cover for the assault convoy. These problems, however, would be largely overcome at Brunei Bay and Balikpapan, thanks to the hard lessons of Oboe 1.

But it was poor intelligence about the state of Tarakan airfield that caused the overriding problem. The level of damage to the airfield, combined with appalling weather and enemy interference, meant that air support could not be provided from Tarakan for the Brunei Bay landing and the strip remained too rough to accommodate Beaufighters. Nevertheless, the RAAF’s airfield construction engineers were able to overcome terrible conditions to make the strip suitable for fighter operations just ahead of the Balikpapan landing. This allowed 78 (Fighter) Wing to mount a creditable effort from Tarakan and to stage through Sepinggang in support of both the 7th Division and the wider Borneo campaign. Indeed, the airfield construction engineers and the men of 78 Wing rightly regarded their efforts as a job well done. And had the war continued, as all expected it would, the RAAF squadrons based at Tarakan would probably have continued to play a useful role.

So was Tarakan a wasted effort? I think it would be fair to say, with the benefit of hindsight, that Oboe 1 was not essential to the success of the Borneo campaign. But to describe it simply a failure overlooks what was achieved at great cost and under very difficult conditions. Amid all the controversy, this positive side of the Tarakan leger should not be forgotten.

Further Reading

Coombes David, Morshead: Hero of Tobruk and El Alamein, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2001

Horner, David, High Command: Australia and Allied Strategy 1939-1945, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1982

James, D. Clayton, The Years of MacArthur: Volume II 1941-1945, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1975

Johnston, Mark, Whispering Death: Australian Airmen in the Pacific War, Allen and Unwin, Melbourne, 2011

Long, Gavin, The Final Campaigns, Australia in the War on 1939-1945, Series 1 (Army), Vol VII, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1963

Odgers, George, Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, Australia in the War of 1939-1945, Series 3 (Air) Volume II, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1957 (Reprinted 1968)

O’Lincoln, Tom, Australia’s Pacific War: Challenging a National Myth, Interventions, Melbourne, 2011

Rayner, Harry, Scherger: A Biography of Air Chief Marshall Sir Frederick Scherger, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1984

Stanley, Peter, Tarakan: An Australian Tragedy, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1997

Waters, Gary, Oboe Air Operations Over Borneo 1945, Air Power Studies Centre, Canberra, 1995

Wilson, David, Always First: RAAF Airfield Construction Squadrons 1942-1974, Air Power Studies Centre, Canberra, 1998

[1] Odgers, Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, p. 456

[2] NAA 1966/5 383, RAAF Command Report of Oboe One Operation, p. 2

[3] Stanley, Tarakan, pp. 96-97

[4] Waters, Oboe Air Operations Over Borneo 1945, p. 151

[5] David Coombes, Morshead: Hero of Tobruk and El Alamein, Oxford University Press, Melbourne 2001, p. 196

[6] Mark Johnston, Whispering Death: Australian Airmen in the Pacific War, Allen and Unwin, Melbourne, 2011, p. 413

[7] Odgers, Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, p. 458

[8] Stanley, Tarakan, p. 131

[9] David Wilson, Always First: RAAF Airfield Construction Squadrons 1942 – 1974, Air Power Studies Centre, Canberra, 1998, p. 84

[10] Odgers, Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, p. 460

[11] Stanley, Tarakan, p. 165

[12] Odgers, Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, p. 460

[13] ibid

[14] AWM64 15/2, Operations Record Book 1 Airfield Construction Squadron, 28 June 1945

[15] Waters, Oboe Air Operations Over Borneo 1945, p. 55

[16] Stanley, Tarakan, pp. 131-32

[17] Odgers, Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, p. 461

[18] NAA A9186 654, Operations Record Book No. 78 Wing Headquarters, Summary July 1945. These figures do not include another 401 non-operational sorties.

[19] NAA A9186 137, Operations Record Book No. 452 Squadron, 24 July 1945

[20] NAA A9186 654, Operations Record Book No. 78 Wing Headquarters, Summary July 1945

[21] ibid

[22] ibid

[23] AWM 3DRL/6643 2/18, Blamey Papers, Letter Blamey to F.M. Forde Minister for the Army, 7 July 1945

[24] Odgers, Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, p. 486 and p. 488

[25] NAA A9186 654, Operations Record Book No. 78 Wing Headquarters, Summary July 1945

[26] NAA A9186 111 Operations Records Book No. 80 Squadron, Activities for the month of May 1945.

[27] NAA A9186 137 Operations Record Book No. 452 Squadron, 30 June 1945 and 19 July 1945

[28] Long, The Final Campaigns, p. 452

Contact Tony Hastings about this article.