The decimation of Australian Army Sappers on standing patrol during the Battle of Fire Support Base Andersen, South Vietnam Tet Offensive 1968.

Compiled and Written by Peter Scott March 2017

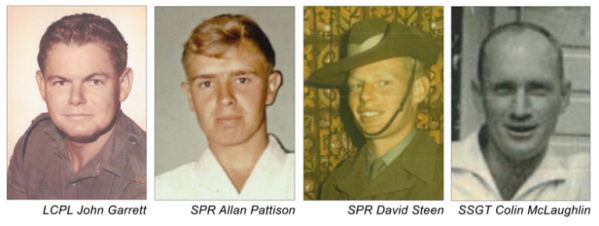

Dedication: To all who fought and died at Fire Support Base Andersen, especially the Sappers of 3 Troop, 1st Field Squadron, Royal Australian Engineers. To the Late Mrs Norma Meehan, whose treasured lost son John Garrett died a brave Australian Soldier at Andersen – may they both rest in peace.

Introduction: This article seeks to look at what has been written about Fire Support Base Andersen and add commentary from some of the sappers who were there on that battlefield. The objective is to make the story of Andersen and its’ soldiers ( Australian Infantry; Australian, New Zealand and American Artillery; and Australian Engineers and Cavalry) more widely known and acknowledged as a significant battle of the Vietnam War, and to honour the service and sacrifice of those who served and those who died there.

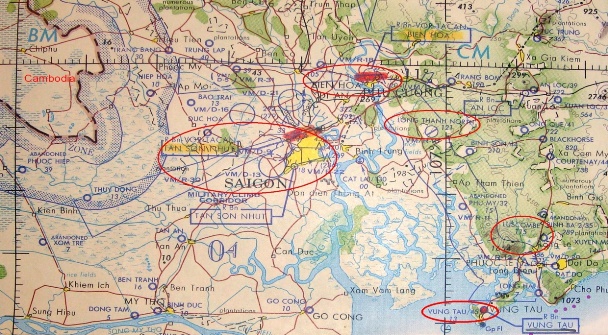

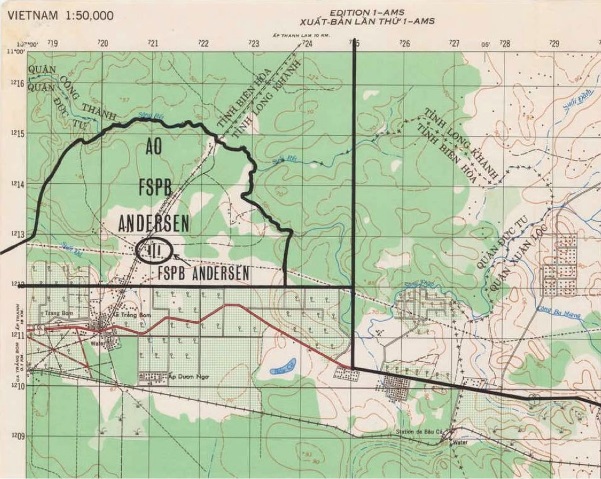

During their Tet Offensive of 1968, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army made numerous fierce assaults on the joint Australian, New Zealand and American manned Fire Support Base Andersen near the village of Trang Bom east of Bien Hoa, on the north-easterly outskirts of Saigon. It was the first time that the Australian Task Force (1 ATF) had operated outside of Phouc Tuy Province, and the Task Force deliberately established fire support bases astride the communist lines of communication, expecting that the NVA and VC would attack and attempt to destroy them. And attack they did, in assaults which became precursors to further fierce assaults on Fire Support Bases Coral and Balmoral just a few months later.

During the battle on the night of 17/18 February 1968, seven Australian soldiers and one American lost their lives, with dozens more wounded, as fierce grenade, mortar and rocket attacks were launched at Andersen by a tenacious and skillful enemy. The defending Australians, Kiwis and Americans were no less tenacious, pouring artillery, mortar, machine gun and small arms fire onto enemy mortar and rocket launch sites, and engaging enemy soldiers as they threw themselves on the wire. The enemy attacks were timed to coincide with the lunar New Year celebrations for the Year of the Monkey, or “Tet Mau Than”, and occurred during 1ATF’s Operation Coburg.

Tragically, an overnight standing patrol sent ‘outside of the wire’ of Andersen by the FSB defence command was decimated during the enemy assault. This patrol comprised a full Section (No. 11 Section) of ten sappers from 3 Troop of the 1st Field Squadron Royal Australian Engineers, acting in the role of infantry, sent to a previously well used knoll feature some 300 metres outside of the protective barbed wire defences of the base. They were ordered to take up a fixed position overnight, lying on top of rocky ground, to provide an early warning listening post to detect advancing enemy forces. Though considered important for base defence, the patrol provided, in reality, a dangerously isolated and exposed target at an often used site well known to the enemy.

During Operation Coburg, Main Force elements of the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong had moved past Andersen for weeks to and from their targets in and around Saigon and Bien Hoa, and Australian Army Intelligence knew this. Notwithstanding the vital contribution of the standing patrols to base defence plans, the decision to continue to deploy listening post standing patrols to the knoll was extraordinarily risky. In the words of Sapper Jack Lawson, one of the survivors of the Engineer standing patrol on the night of the 17th/18th, “we were hung out to dry”.

During enemy assaults in the early hours of the morning the patrol received direct hits from mortar and RPG (rocket propelled grenade) fire, and was virtually wiped out: four of the sappers were killed, with three others wounded. The remaining three were unwounded but heavily traumatised by the brutal nature of the mortar attack and the death of their mates.

In cruel twist of fate, two of the surviving sappers were to be killed in action just one month later in a mine incident during Operation Pinaroo in the Long Hai Mountains south east of Nui Dat. Dark days indeed for the proud men of 3 Troop of the 1st Field Squadron RAE, who in a period of about one month, gave up seven of their number killed, and four more wounded in support of Operations conducted by infantry of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment.

Meanwhile, on that same night inside of the wire of Andersen, another four soldiers were also killed during the enemy attack; they were two 3RAR riflemen and an Australian and American artilleryman, who names are listed in the Honour Roll at the rear of this article. The next morning the bodies of four enemy soldiers, who died on the wire while trying to take Andersen, were searched, then buried onsite by 3 Troop sappers inside of the Base. More dead and wounded enemy had been dragged away in the night by their comrades.

Most tragically of all, the events and sacrifices at FSB Andersen are virtually unknown and forgotten during Australian Government and community remembrances of the Vietnam War, remembrances that disproportionately and repetitively focus on other landmark battles such as Long Tan, Coral/Balmoral and Binh Ba.

In the Official History of Australia’s Involvement in Vietnam On the Offensive The Australian Army in the Vietnam War January 1967-June 1968, Ian McNeill and Ashley Ekins (2003) give a short passing reference to Andersen, but say nothing about the decimation of the standing patrol.

In Paul Ham’s weighty tome Vietnam: The Australian War (2010), there are no references to FSB Andersen at all, nor to ‘Engineers’, nor to the 1st Field Squadron RAE being part of Operation Coburg.

In the Australian War Memorial’s Wartime issue 20, a passing comment is offered by Chris Coulthard-Clark “Three times between 18 and 28 February, Andersen came under attack but each time the Viet Cong were beaten off.” In both cases, there is no commentary of the ferocity of both the enemy assaults and 1ATF response, and no acknowledgement of the Australian soldiers (infantry, artillery and engineers) who died there in violent and traumatic warfighting.

Perhaps the decision to continue to mount standing patrols outside of the wire was unsafe in light of known intelligence on enemy activity and fact that the Base was very much undermanned. A whole Infantry Company was added to the defence of Andersen on the day after the first attack and was sent out to the knoll area. Perhaps battles such as that at Andersen that didn’t result in a resounding victory were seen (and still are) as lacking in ‘merit’ and therefore best forgotten. McNeill and Ekins in On the Offensive refer to Commander Australian Force Vietnam (AFV) MAJGEN Arthur MacDonald being critical of the ‘sheer lack of basic knowledge’ of many junior NCOs and officers at the time, and, despite believing that Operation Coburg was a success and that the statistical results were considerable, “they were not spectacular…” (pages 303,304)

Not spectacular! Not enough dead on both sides? By what ratio did the enemy body count have to exceed that of 1ATF to please AFV Headquarters?

General MacDonald, according to Paul Ham (2010), was a usually grumpy man who mistakenly believed that the Viet Cong were virtually defeated in Phouc Tuy, and subscribed to the American view that body count and kill ratios were a measure of success. His disparagement was perhaps the blow that snuffed out the likelihood of any recognition for the brave soldiers who fought at Fire Support Base Andersen during the Tet Offensive.

Background to Operation Coburg: In the last months of 1967, allied intelligence had detected sure signs of communist plans for an offensive, timed to coincide with the traditional Vietnamese celebrations of the 1968 lunar New Year at the end of January. These signs, however, provided no clues about the likely enemy targets and methods, or the nature of what was planned. No one knew that the North Vietnamese leadership, having become no less frustrated than the allies at the apparent military deadlock that had developed in the war, had opted for a massive strike which they hoped might lead to decisive victory. (Wartime, Issue 20, AWM)

In response to this intelligence, the then Australian Forces Commander MAJGEN Douglas “Tim” Vincent (MAJGEN MacDonald’s predecessor) offered the use of the 1ATF outside of Phouc Tuy Province. American and other forces were put on full alert and positioned to deal with any attacks that the NVA and VC/irregular forces might launch.

US Commander LTGEN Fred Weyand had asked Vincent to send 1ATF Forces to neighbouring Bien Hoa province to operate alongside American forces preparing to block any thrust by NVA and VC forces against the vast complex of military installations around Bien Hoa city and adjoining Long Binh, located some 25 kilometres north-east of Saigon.

The task force move, codenamed Operation Coburg, involved the bulk of 2RAR /NZ (ANZAC) and 7RAR, along with supporting armoured cavalry, artillery and engineers. Left behind in the 1ATF base at Nui Dat, until later rotation into Operation Coburg, was 3RAR, while a New Zealand company of 2 RAR/NZ held the Horseshoe feature near Dat Do.

By the afternoon of 24 January 1968, the first two Australian battalions were on the ground in their new area of operations, named AO Columbus, on the eastern boundary of Bien Hoa with Long Khanh province, and about 55km north of Nui Dat. Almost immediately patrols began having contacts with enemy forces, and these increased over the next four days in both scale and frequency as a number of enemy camps were uncovered and attacked.

1 ATF: Who was deployed and where: Initially, along with 1ATF Tactical Headquarters and Taskforce Maintenance Area forward echelon, 2 RAR/NZ and supporting Combat Arms were deployed to FSB Andersen, with 7 RAR and support at the western end of the AO towards Bien Hoa at FSB Harrison.

Supporting Combat Arms were 4th Field Regiment Artillery RAA including New Zealand 161 Battery (105mm howitzers) and the Australian Locating Battery (artillery radar), A Squadron 3 Cavalry Regiment armoured personnel carriers, 1st Field Squadron RAE forward Headquarters with 1 and 2 Field Engineer Troops and plant operators for construction and combat support tasks including provision of water points.

Patrolling and Blocking: Despite the precautions that had been taken at General Weyand’s instigation, the Bien Hoa-Long Binh complex was still heavily attacked by 5 VC Division, resulting in much damage to aircraft, buildings and facilities. The role of the nearby Australians was then promptly changed from reconnaissance-in-force (operations to gather information especially about the strength and positioning of enemy forces) to intercepting and blocking enemy forces as they attempted to move back to their sanctuaries. In the words of the commanding officer of 7RAR LTCOL Eric Smith, for the next few days Viet Cong flowed past his company positions “like water”. During this period, the enemy was at times demoralised and disorganised and avoided contact, and many were caught in platoon ambushes set by the Australians.

The Enemy: Moving through AO Columbus comprised thousands of main force 84A Artillery (Rocket) Regiment NVA equipped with 122-millimetre rocket launchers and 82-millimetre mortars, and Viet Cong 5 Division troops including 274 and 275 infantry Regiments and a small element of the Dong Nai Regiment.

They were well trained and indoctrinated, and equipped with Chinese made copies of AK47 assault rifles, rocket launchers plus ample supplies of ammunition, mines, grenades and explosives. As a general rule they were aggressive and, even when faced with serious losses they bounced back. If they chose to fight in a particular circumstance, they did so with tenacity and skill. They wore an assortment of uniforms from green or blue-grey to black, and, while not well fed, had caches of rice hidden locally for their use. They staged through numerous well constructed base camps with connecting communication trenches and some surgical and dressing stations. They tended to move in small groups accompanied by local guides, often under cover of night along well planned trail systems and river crossings. The Australians used knowledge of this to set up successful night ambush positions.

The Role of 1st Field Squadron Engineers.

The majority of the Engineer Squadron was deployed with the 1ATF Operation Coburg, under their OC Major John Kemp. This was the first time that all three Troops of the Squadron’s Combat Engineers were deployed to the same area, operating under operational control of their respective infantry Battalions… 1 Troop was attached to 2RAR/NZ, 2 Troop to 7RAR and 3 Troop to 3RAR to provide close Engineer support. It was 3 Troop that drew the short straw.

1 Troop 1 Field Squadron RAE: When 2RAR/NZ went in on 24 January, many enemy bunker systems were located and destroyed by attached 1 Troop sappers.

On the night of 31 January/1 February, the VC village of Trang Bom just south of Andersen was the site of fierce fighting and destruction. It was overrun by the Viet Cong but the RF Post held out until first light. D Coy 2RAR/NZ with A Sqn 3 Cav Regt, supported by a Combat Engineer Team and Mini Team respectively, began clearing operations towards Trang Bom. The road between Anderson and the village had been mined during the night and was cleared by the engineers the next morning (Florence 2013).

2 Troop 1 Field Squadron RAE: 7 RAR deployed with the initial task of securing the FSBs (Harrison and Andersen) and establishing a series of blocking positions. Two combat engineer teams from 2 Troop were placed under the operational control of 7 RAR from 10 January, while 3 mini teams of 2 sappers were placed with A Squadron 3 Cavalry Regiment’s amoured personnel carriers from 11 January, with a further team added on 20 January due to the threat of mines.

Prior to this time Andersen was a hastily built American position which was re-built and fortified to a higher level, mainly by the sappers of 2 Troop under LT John Jasinski.

The start of the standing patrols: It was at this time apparently that the first sappers (deployed as a full Section) were thrown into the role of front-line infantry to mount the standing patrol outside of the wire, at a listening post originally established by the Americans, some 300 metres to the west of Andersen, and near a knoll /quarry site referred to by the 2 Troop sappers as ‘the lone pine’.

It is not known who originally committed Engineers to this task, but the decision to send these overnight patrols to the knoll indicated some degree of ‘expendability’ of whoever was sent out from FSB Andersen, including trained infantry.

Colonel John Kemp AM (Retd) (2016): The standing patrol task was accepted by the Engineers as within their capabilities as one of the shared responsibilities of base defence. As it transpired, the level of combat training of whoever was on the standing patrols had nothing to do with the outcome. It all came down to fate and circumstance.

Former OC A Company 3RAR at Andersen, now Major General (retired) Brian ‘Hori’ Howard recalls (2016): Andersen was larger than a normal FSB due to the presence of the US Artillery Battery and the APCs, so it needed more protection and of course patrolling than a smaller FSB. The patrol program would have been worked out by the 3RAR Battalion HQ not 1 ATF and I would have been surprised if the Engineer troop had not been included in it. After all, their stated secondary role was to operate as Infantry. However, be assured that they weren’t tasked as Infantry but as well as Infantry.

Former 2 Troop Sapper (later CPL on 2nd Tour) John “Ben” Benningfield recalls being out at the listening post on the night when the fight started at Trang Bom, in a standing patrol comprising himself and Sappers Dave Matulick, Geoff “Smokey” Craven and Warren McBurnie, and led by Cpl Mick Grey. From some distance they observed enemy soldiers in numbers, moving down the road in the darkness, laying anti-tank mines and booby traps, and so the next morning were able to help locate the killer devices as the road was cleared.

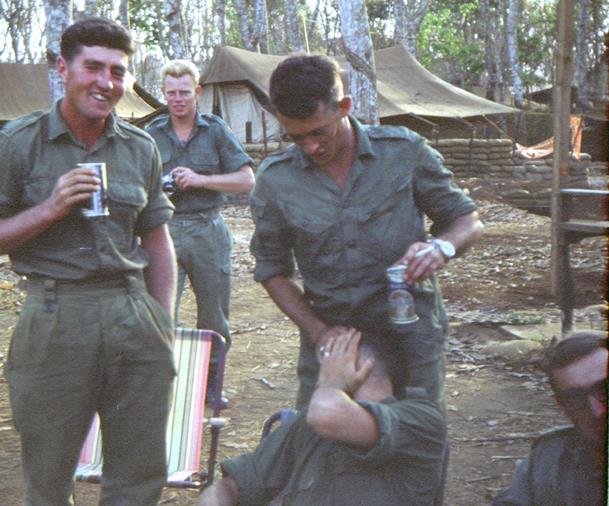

3 Troop 1 Field Squadron RAE: Recently arrived in Vietnam, Infantry from 3RAR were rotated into (the end of) Operation Coburg as its first major operation In Country, and was its’ first opportunity to work with what it called ‘flanking units’. Of those ‘flanking units’, 3 Troop 1st Field Squadron RAE, provided Engineer support, including Combat Engineers.

3RAR ‘inherited’ FSB Andersen, with all its faults, from 1ATF who took the original decision to expand a base initially established by the Americans. In its After Operation Analysis of Operation Coburg, 3RAR noted: The most significant lessons learnt were …. FSBs should be located away from civilian habitation ….should be clear of civilian traffic routes and garden areas ….should have a clear 200 metres around the FSB …. adequate digging with overhead protection should be a priority…. all personnel must sleep below ground level and if time permits, with overhead protection …. civilians must be kept away from FSB defences by quick aggressive action. In the lead up the first NVA/VC attack, one Company of 3RAR was allocated to remain at Andersen.

Sapper Peter Macdonald: When 3 Troop arrived on FSB Anderson it was obvious someone had been there before us as the perimeter was fenced in barbed wire and the base was generally untidy. Even at this early stage I pondered our purpose, it appeared our role on FSB Anderson was to act as infantry. We were combat engineers who work with and can carry out a role as infantry, but we were not (fully) infantry trained.

As we were working hard finalizing our positions and digging our shell scrapes we noticed a sky crane coming from the south with a D4 hanging below it, the dozer was lowered and began digging a trench. A short time later the sky crane returned with 12×12 planks and laid them across the completed trench, then hooked up the D4 and took it home. At this point we were all wondering who was going to fill the 1000 plus sandbags to cover trench. Our concerns were answered through the return of the sky crane with a cargo net hanging below it containing the 1000 plus needed sandbags. The sandbags were lowered to cover the trench and there it was in all of its splendor, the Americans’ new ‘safe’ home on Anderson. The only thing missing was the inhabitants and they arrived shortly after in choppers and walked into their new home without even lifting a spade. We all agreed we were in the wrong army.

Deficiencies at Andersen were particularly evident to the New Zealand 161 Artillery 161 Battery. In New Zealand’s Vietnam War (2010), Ian McGibbon writes: ‘The 18th brought by far the most dramatic moment of their sojourn at Andersen, the one that demonstrated marked deficiencies in defensive preparations at the base. The general attitude to digging in had been ‘half hearted’, a lack of materials prevented overhead cover being provided, communications were deficient and the defences were not properly coordinated. FO Mike Harvey had great difficulty in getting any US battery outside the area to register defensive fire targets, finally doing so on the 17th and then registering only two. Civilians from the village to the south [Trang Bom] had been allowed to come close to the base. ‘Some of the local girls were even conducting business 200 m from the perimeter wire,’ Harvey observed later. Under cover of this civilian presence, the enemy had been able carefully to study the base dispositions.

Sapper Barry Gilbert had been in a Splinter Team with A Coy 3RAR and walked back into Andersen with 3RAR riflemen after a reconnaissance patrol. Rather than staying overnight with the infantry, he asked to go to join his 3 Troop mates on their perimeter wire defence sector next to the American 155mm howitzers. Barry had been trained as a radio operator and when he learned that the 1 Field Sqn engineers had been tasked to do standing patrols out at the listening post, he volunteered to go out with the radio. However Lance Corporal John Garrett, who was on the patrol for that night, said that he would take the radio as Barry had already had his turn with 3 RAR and should stay inside with the Troop. Barry was understandably devastated when the boys were hit that night, not least at the realisation it could have been him but for the gesture of John Garrett.

Sapper Peter MacDonald: Section Corporal Merv Dodd informed us on his return from an Infantry ‘O Group’ that two battalions of the North Vietnam Army had been detected and were moving south. He also mentioned strong VC movement had also been detected in the area and we needed to be prepared. The thought of what could happen was naturally a little worrying.

Clearing patrols were conducted at dusk each evening by A Coy. The patrol would exit their position and move across the 3 Troop perimeter and make arrangement to enter back through the American lines. It was essential the clearing patrol was finalized by 1849 hrs, as the Americans commenced their clearing patrol at 1850 hrs. Their clearing patrol consisted of 10 minutes of machine gun and small arms fire out from their perimeter until sundown.

Click here to read Part 2

Contact MHHV Friend about this article.