There are numerous soldiers’ descendants who have recounted their fathers’ incarceration in Europe or Asia during the Second World War, but it is a rare experience to read the autobiography of an Australian prisoner of war.

Granquist, very late in his life takes the reader through his boyhood in Blaxland, NSW during the Depression; and joining the militia in 1938, then putting up his age to enlist in 1939 in the 2nd/4th Battalion.

Paperback 224pp RRP: $19.99

There is a brief description of the convoy to the Middle East prior to his battalion’s move to Palestine for additional training. During periods of leave the ancient Christian sites in Jerusalem were visited. A six-week signals course preceded Charles’ 6th Division’s move to Alexandria in readiness for its campaign in the Western Desert. New Year 1941 saw Charles 130 miles west of Mersa Matruh before continuing to successfully overrun the Italians at Tobruk. After a period of heavy artillery bombardment in Benghazi, 6th Division was relieved by the 9th Division and then moved back to Alexandria.

After a period of leave, the next theatre for Charles was Greece – in mid-April 1941 at Larissa (300km north of Athens) with the threat of two German armoured divisions pushing southwards. Unable to match the German firepower and Stuka bombing, withdrawal became the only option for the Allies. After being wounded in the chest, Charles opted to leave his battalion and seek evacuation via medical units. He made his own way south to Corinth and after a few days on the run and some medical aid, Granquist joined up with a small group who camped by a beach for a week waiting for a boat engine to be repaired. On 9th May as the group embarked the Germans nabbed them!

Granquist’s first reactions at becoming a prisoner of war were of shame and guilt. He was transported to Stalag 18A in Wolfsberg Austria to be employed on road building. Red Cross parcels provided a most welcome relief from meagre rations, and tinned items could be used in preparation for escape bids. His first escape was on 10th April 1942 and he was free for seven days before Italians recaptured him. They placed him in a civil jail in Udine before returning him to Stalag 18A and 28 days of solitary confinement (bread and water diet, one-hour exercise per day and one shower per week).

A rumour that prisoner non-commissioned officers were to be moved to Poland saw Charles ‘swap identity’ with an Englishman who was desperate to avoid work gangs. A hastily planned an escape towards Yugoslavia provide four days of freedom; with a new regime for disciplinaires including interrogation in Landeck in the Tyrol, then to the Markt Pongau prison camp before ending back in Stalag 18A and more solitary confinement. At this stage Charles’ mail and Red Cross parcels were going to Poland. In Charles’ next disciplinaire camp a tunnel was built with escape through Hungary, Bulgaria and Macedonia into Turkey envisaged. Again, after sighting Vienna, police recaptured him. Two weeks at Feldkirchen, time at Markt Pongau, then Stalag 18A again.

After being sent to a disciplinaires’ camp at Loeben in East Austria, the prisoners were set to work maintaining the local railway lines – travelling to and from work sites by passenger train.

Clandestine radios helped buoy prisoners’ spirits with news of the Germans’ defeat on the Eastern Front. By winter 1942 the ‘identity swap’ was revealed, so back to Stalag 18A for Charles.

Spring of 1943 meant another disciplinaires’ camp, at Hermagor, where quarry work was necessary. At the end of summer, another escape attempt in the direction of the Italian Alps ended in surrender to Italian soldiers just one day before Italy’s surrender on 3rd September. By June 1944, plans were again made to escape to the Dalmatian coast – this time fourteen days on the run preceded the return to solitary. Charles estimated he had done 190 days in solitary but being involved in “criminal” activities eased his feelings of guilt over becoming a POW.

Having then deciding to see the war out without further escape attempts, Charles befriended Ann, one of a group of Ukrainians brought into the camp as slave labourers. Romance blossomed, and on liberation on 8th May 1945 (after Charles had served four years less one day as a POW), they made their way to Naples and were married in Resina before heading to England for repatriation to Australia. Charles arrived in Sydney Harbour on 30th November 1945, and Ann followed in March 1946.

Discharged from the Army in June 1946, Charles received a Citation for a Mention in Despatches for distinguished service gazetted in January 1947. The following year he rejoined the Citizen Military Forces in his original 30th Battalion as the signals sergeant. Commissioned in 1949, he was promoted to captain in 1952 to command Headquarter Company.

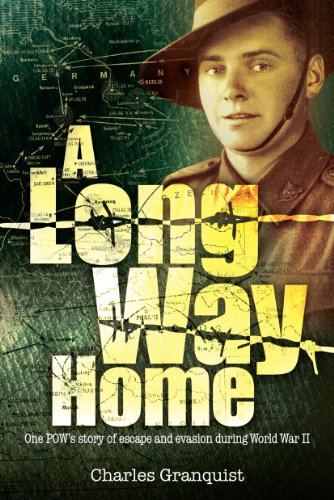

Written in a most readable and, at times, quite humorous form, there is a generous number of photographs from childhood to old age, overseas sites during the war, sketches, paintings, and maps. The chapter titles are rather ‘tongue in cheek’, and there is no index.

Reviewed for RUSIV by Neville Taylor, March 2018

Contact Royal United Services Institute about this article.