A remarkable logbook came to light in mid-2018, after 100 years in private hands.

An anonymous donor to an RSL and a call from its Secretary revealed an old ledger, marked ‘Secret S232A Cypher Log’. Inside lies the remarkable hand-written personal diary of one Petty Officer Stoker Andrew Henley, from Clayton, Victoria.

Born in Collingwood on 12th November 1887, Henley joined the fledgling Australasian Naval Force (ANF) on 4th November 1908.[1] Transferring to the new Royal Australian Navy on 14th October 1912, Henley served in the Navy continuously to 1930. He remained in the Royal Australian Fleet Reserve for a further 5 years and was recalled for service during WWII between May 1942 and December 1943.[2]

In June 1918, having returned to Australia, Henley married and at the end of his naval service he retired to Clayton[3] where his parents had been poultry farmers in the district since at least 1913. In May 1918 Andrew Henley’s name was included in the Clayton Avenue of Honour, indicative of his parents’ connection to the district.[4] For his service Henley was awarded the 1914/15 Star, British War Medal and Victory Medal. A Long Service and Good Conduct Medal was awarded in 1923.[5] Henley died in 1966.

Henley’s logbook, with the heading of Cruise of HMAS Melbourne during Great War 1914- Part II, covers his service in HMAS Melbourne in the North Sea for the period 26th October 1916 to 4th January 1918. Still missing is Part I which would cover Melbourne’s war years from August 1914 through to October 1916. In January 1918, when the journal ends, Henley was repatriated to Australia for leave having served three long and arduous years of active service.

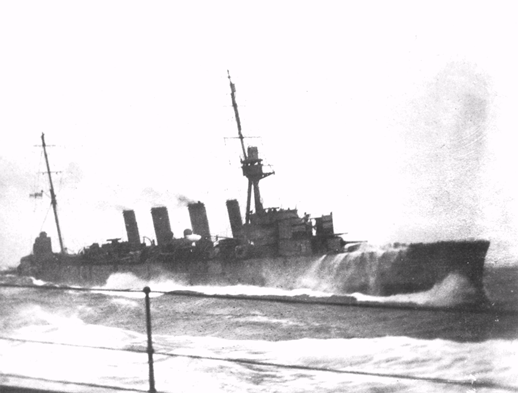

The story of HMAS Melbourne is now well documented, most comprehensively in The Forgotten Cruiser: HMAS Melbourne 1912-1928,[6] but Henley’s journal adds new first-hand accounts into that period in the North Sea over 1916-1918. At that time, Melbourne was at port in Scotland’s Firth of Forth at Rosyth, and occasionally at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. Melbourne was part of the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron of 4-6 light cruisers – the self-named ‘Suicide Squadron’. It was a small part of a huge British fleet stationed to protect Britain from naval attack, maintain the blockade of Germany but most of all to engage the German High Fleet if it chose to leave port. Serving alongside sister light cruiser HMAS Sydney (of Emden fame) and the battlecruiser HMAS Australia, the crew of Melbourne faced an uncompromising, dirty and dangerous war.

Henley documents the always dreary and often atrocious weather, continuous drills, alarms and patrols, poor food, illness, lack of leave and the exhausting physical labour of re-coaling at all hours. It was not a glamourous life and home leave in 1918 could not have come fast enough, with discipline and certainly morale fraying around the edges. He sets the tone from the first sentences – ‘We are now in North Sea in earnest and candidly speaking I am afraid a few of the lads would prefer to be in the West Indies. Not for the comfort they would get there but to be able to dodge the extra drill exercises that have to be continually endured.’ [7]

By this time the biggest naval battle of the entire war had already occurred. The Battle of Jutland over 48 hours to 1st June 1916 had ended indecisively but not inconclusively, given that the German High Fleet had retreated to port after heavy losses on both sides. Yet Melbourne had missed the fight, away from area receiving a refit at its birthplace at the Cammel-Laird shipyards at Birkenhead near Liverpool, following its arrival from blockade duties in the Caribbean and the east coast of the USA. Henley wrote – ‘We certainly have not had a Naval fight yet, but we are living in hopes that in the near future we may have the chance of proving of what material we are made.’ [8] His journal shows that nonetheless the crew of Melbourne were indeed made of the toughest material where endurance and stoicism were needed, and especially as winter approached.

Nerves were stretched by constant alarms and the pressure on stokers to fire up the boilers and get to sea, ‘everyone dashing about and getting dizzy and tumbling over each other’, sometimes with as little as half an hours’ notice. The constant threat of action and waiting for a call to ‘general quarters’ further frayed the nerves long with the threat of submarine attack, running into floating mines released by enemy trawlers and possible attacks by enemy Zeppelin air ships. Henley wrote: ‘These are the spasms we are often subjected to and the ones that are gradually wearing away the hearts of the crew…’ [9] The stress can only be imagined when the effects of restricted leave, poor food, steaming in shocking sea states, low light or darkness are added to the constant need to be ready for operations.

On various patrols and ‘evolutions’ at sea, Henley describes how in heavy seas waves would break over the ship, ‘completely burying us under the flying waves’, as she maintained a zig-zag course to confuse enemy submarines. ‘Many a wave went completely over our funnel and fore bridge’, with accompanying destroyers sometimes showing a third of their keels as they made ‘a rare old fuss of the elements’.[10] Collisions in these sea states were not rare, and resulted in serious damage to the ships involved, sometimes catastrophically. Even in port, the bitterly cold and bleak weather – sleet and hail pummelled the ship sides – made life challenging. While steam was maintained 24 hours a day, enough to get underway at 12 knots, it was not enough to heat the whole of messdecks and quarters throughout the vessel.

On 21st December 1916, Melbourne experienced a shocking storm at sea., when, wrote Henley, ‘not a few of us thought each lurch would be the last’. These journal entries are worth a full exposition, if only to properly explain the terror and mayhem that many of the crew must have felt at the time. Two men were lost on that terrible day:

“Everything moveable on deck went overboard. Projectiles were thrown out of their racks and sent spinning in all directions. Sheets of steel and wooden partitions were torn out and blown overboard. At 10:30am when the storm was raging a breechblock on a gun on the quarterdeck opened and kept swinging. One of the seamen, against orders, went from under cover to secure it No sooner had he got in the open than a huge wave swept him overboard and in the flying spray and heavy seas he vanished. Nothing was ever seen of him again.[11]

We could not stop or turn or do anything. A signalman was sent aloft to see if he could locate him but. No sooner had he got into the rigging when a heavy sea washed him loose as if he were a fly. He was dashed to the deck in smashed condition and before anybody could move another wave washed the body overboard, he vanished immediately.[12] Before the day was out 9 men were in the sick bay with broken arms, legs and collar bones many injuries such as cuts and bruises and smashed fingers were without number.

…nobody had a bite to eat all day and the mess decks were in terrible disorder. Some of the decks were a foot deep in water. Racks and lockers were wrenched from the bulkheads like paper and hurled about. Nobody turned in during the night and several times we had to stop engines and get pushed along by the waves when the rolling became so heavy. Seas constantly went down the funnel and everywhere was flooded. Stokehold plates and skids of coal were washing about due to the quantity of water in the bilges. [13]”

Henley noted that when land was sighted the next morning the Melbourne found herself 200 miles [321 km] off course. The crew were finally able to get on deck and the effects of the storm were immediately evident, with bridge stantions twisted, much of the upper deck beams strained and two guns damaged.:

“…a sight of wreckage and disorder prevailed. The deck was bare of anything bar guns and a few projectiles still were wedged where they rolled when they came adrift. Cordite lockers weighing 15 cwt [750kg] were gone and boats smashed. Wireless aerials were broken and lying on top of funnels. 11am we crawled into Rosyth a forlorn and battered cruiser.[14]”

The other cruisers also lost men overboard in the storm, including Sydney, and one of the battlecruisers had a loose projectile strike and explode with the loss of 16 men. Two of the accompanying destroyers collided in the weather and sunk – all hands were lost, over 200 men. It had been a terrible experience for everybody.

Christmas 1916 was spent on board with no strong drink and in readiness. Gifts from the people of Australia were distributed – meant for Easter the previous year, just arrived. Temperature below 32° [0°C] with snow and frost. At 2 am orders to light up and go to sea. Henley recorded in several places in his journal as to how fed up the men were, and lack of leave was a major cause of discontentment. When the ship was under two hours’ notice to go to sea no leave was given; if 2½ hours or more, then 2 hours was allowed, but only between 1:30-4:30pm. When the liberty men went ashore they paid 4 pence for a ticket entitling them to one pint of beer – and once mustered to return to the ship they pass a hotel where the pints were laid out on the grass. The men drank their permitted pint and the march to the ship continued.

Henley also described at length periodic attacks of German measles, mumps, colds and influenza. When influenza struck across the fleet ships were quarantined. At one point with the Melbourne, Sydney and Australia all flying the ‘yellow jack’,[15] wrote Henley, they were being called the ‘Chinese Fleet’. Along with accidents and injuries, lung and heart problems also affected the men, especially those toiling below decks. Coaling was a constant and breathing in coal dust over several years had a terrible effect on the men’s health Stokers on the ships laboured mightily not only to coal as quickly as possible but also to beat the other squadron ships in the tonnage loaded from the colliers alongside. On the last day of 1916 Melbourne coaled 360 tons [367,000kg] or 173.8 tons per hour – Sydney only managed 230 tons and an average 230 tons. As Henley put it, ‘it is not the best of jobs shovelling up coal and snow mixed.’

In early 1917 when splits were discovered in the ship’s boilers, the ship was ordered to return to the Cammel-Laird shipyards one again for a major overhaul and the addition of new technology. ‘Needless to say’, said Henley, ‘cheers were heard in various parts of the ship’.[16]

Despite the snow and ice, half the ship’s complement at a time were able to take leave. The ship repairs were completed by the end of June 1917. [17] Melbourne returned to Scapa Flow, where on 9th July, walking the upper deck at 11pm having a last cigarette before turning in, Henley witnessed the massive magazine explosion which suddenly destroyed the dreadnought HMS Vanguard. All but two of her 1300-man complement were killed. It was another reminder of the ever-present dangers of service in warships on active service.

In January 1918 the ship narrowly avoided being torpedoed. Two hours later a submarine was sighted – Melbourne ‘charged the spot’ and dropped a depth charge but with unknown results. Henley’s journal continues recording the ongoing convoy escort duties to and from Norway and patrols against raiders, submarines and the ever-present mines until it stops mid-sentence on 4th January 1918. According to Henley’s service record, he left Melbourne on 13th April 1918, two weeks before the ship once again returned to Liverpool for a refurbishment, application of a dazzle camouflage scheme and to be fitted with an aircraft launch platform over the front gun. Henley was one of those who after years of continuous service was given home leave, returning with four service chevrons on his sleeve for 1914-17. His war was over, although his full-time naval service continued to 1930.

Henley’s journal in the old cypher log book reveals much about a sailor’s life on board an Australian warship in the North Sea during the Great War. It is interesting on several levels. It adds a first-hand account to patchy records from this ship during that period and provides new information not previously known.[18] It never mentions names – presumably a self-imposed security measure. Even the Captain is rarely mentioned. Life below decks in the Engine Room holds of the ship also meant that activities above deck were often not witnessed. Rumours abounded[19] and sometimes the stokers did not even know where they were until the destination was reached. The war in general was also rarely mentioned; Henley’s world was focused on the day-to-day of his ship, his squadron and the North Sea in which Melbourne operated.

It is remarkable that given the back-breaking work of coaling, being on duty in the bowels of the ship with the attendant physical and mental strain of fear, uncertainty and possibility of sudden death or disablement from accident or enemy action alike, that a journal was kept by a stoker at all. That it has survived for 100 years is equally remarkable and it is to be hoped that the missing Part I of the journal appears in another ‘Secret S232A Cypher Log’ at some time in the future, so that Andrew Henley’s Cruise of HMAS Melbourne during the Great War 1914- can be read in its entirety.

[1] The ANF contained sailors from both Australia and New Zealand. The men were effectively Royal Navy Reserve ratings who signed on for an initial 5-year period and served in the Royal Navy ships of the Australian Squadron. When Henley joined the ANF in 1908 as a Stoker II Class with Number 1138 he gave his occupation as ‘poultry fancier’. He served in HMS Psyche, a Pelorus class light cruiser in the RN on the Australia Station, which was later transferred to the RAN. Henley re-engaged in 1910 as a Stoker I Class for a further five years and transferred to the RAN in 1912 as a commissioning crew member of HMAS Melbourne.

[2] RAN Service Record 7242 Andrew Henley, National Archives of Australia.

[3] He first appears on the Clayton electoral rolls in 1934.

[4] A Gunner G.H. Henley was also recorded on the Clayton Avenue of Honour – but he cannot be identified. Dandenong Advertiser and Cranbourne, Berwick and Oakleigh Advocate, 27 June 1918

[5] RAN Service Record 7242 Andrew Henley, National Archives of Australia.

[6] Kilsby, A.J., The Forgotten Cruiser: HMAS Melbourne 1913-1928, Longueville Media, Sydney, 2013

[7] Henley Log, 26th October 1916.

[8] ibid.

[9] Henley Log, 27th October 1916.

[10] Henley, 1st November 1916.

[11] Able Seaman William John Watson from Seymour, Victoria, one of the original commissioning crew. The Forgotten Cruiser, p61.

[12] Signalman Ernesto Campagnolo from Walhalla, Victoria. The Forgotten Cruiser, p61.

[13] Henley Log, 22nd December 1916.

[14] ibid.

[15] Quarantine flag.

[16] Henley Log, 27th January 1917.

[17] Whilst in drydock at Birkenhead, Stoker Edwin Banthorpe Hancey, a South Australian, died after having tonsils removed. Curiously Henley’s journal makes no mention of it, possibly because Hancey only joined the ship in January 1916 while Henley was both a Petty Officer and an ‘original’. There were 45 stokers on the vessel.

[18] For example, at the refit in 1917, anti-mine underwater towed devices were fitted to the ship, designed to cut tethered mine cables and bring the mines to the surface where they could be destroyed by gunfire.

[19] For example, Henley details a serious mutiny on the battlecruiser HMS Canada at Scapa Flow in 1917. No reference to it otherwise has yet been found by this author.

Contact Andrew Kilsby about this article.