Ottoman authorities arrested and deported 230 Armenian political, religious, educational and intellectual leaders in Constantinople 500km east to Angora (now Ankara) on the eve of the ANZAC landing on Gallipoli. Thus began the rounding up of the Armenian elite and the extermination of Turkey’s Armenian subjects. Eventually more than half of the Armenian two million were killed, exiled or died of disease.

Paperback 323pp RRP: $34.99

In October 1854 the young Armenians servant of a Ballarat Catholic priest was arrested for not having a mining licence. Despite being exempt from the requirement he was found guilty – resulting in public backlash that led to the Eureka Rebellion in December 1854. Armenian periodicals of the day encouraged Armenians to migrate to Australia, and in the ensuing 50 years many came to Australia to create a niche for themselves in Australian society.

As reports from the US and UK press reached Australia, they were included in war news in Australian papers, so the Armenians’ plight became widely known here by late 1915. Britain quickly responded with books on the subject being widely read. The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire 1915-16 (November 1916) became a major factor in appeals for funds for the Armenians to be established in Victoria. Recruiting drives included mention of the plight of the Armenians. The cause gaining increased support during 1917 and 1918.

Thousands of destitute Armenians were found by the Allied forces in the deserts of Syria and Mesopotamia, as were the corpses of those who had not survived. The establishment of relief centres did much to ease the plight of survivors. Promises made by the Allies during the war to restore the national rights came to nothing. Expected sanctions on Turkey for their ill treatment of prisoners and the Armenian massacres were never imposed. Armenian testimony in war crime trials was excluded ‘to obviate criticism of perceived bias’. Mustafa Kamal in May 1919 was dispatched to oversee the disbandment of remaining Ottoman forces in the eastern province, but instead organized a resistance movement against Armenian and Greek political aims. Moving into the political arena he then worked to defend Turkish rights – ‘Turkey for the Turks’ became the catch-cry.

By February 1919, relief on a massive scale commenced arriving for the Armenians on a number of American freighters. Among the relief workers was Californian Congregational Minister Loyal Wirt who had made a massive impact during 1901- 07 when he lived in Australia. Australian papers continued to report on the Armenians’ plight, and the peace movement during the War transferred to an emerging human rights agenda. With over 200.000 Armenian refugees scattered through Eastern Mediterranean countries, Wirt was commissioned to establish Armenian relief committees in Pacific countries. Wirt reached Australia in May 1922 and soon had numerous philanthropic organisations eager to help.

He proposed a ‘mercy ship’ to ease the situation in Armenia. The Hobson’s Bay sailed for Constantinople from Melbourne on 6 September 1922, well stocked and carrying the first of a number of missionaries who offered their services. Adelaide-based Reverend James Cresswell made a tour of orphanages in Lebanon, Syria and Palestine containing Armenian children as well as refugee centres in Greece, Turkey and Armenia in 1923. He encountered numerous Australian working in various capacities at many locations and his reports on return stirred Australian communities to even greater efforts.

Sydney social worker Edith Glanville, influenced by Wirt, worked tirelessly towards the (free) shipping of donated flour and other ‘raw materials’. By 1925 Australia was feeding 6500 children through the Save the Children Fund.

Australian women played a considerable part in the League of Nation’s Commission of Enquiry for the Protection of Women and Children in the Near East in the early 20s. Eleanor MacKinnon, in September 1925 spoke of the frustration in aid works when, after orphanages had been established, the Turks had revisited and scattered the Armenians yet again. University of Adelaide Professor Darnley Naylor wrote in the Adelaide Register that the ‘Great Powers’ had promised rest and security for the Armenians, had broken their word, and left them to the tender mercy of the Turks.

In 1926 Glanville became an officer with the League of Nations investigating the needs of refugees. After two years she returned to Australia and created a fund called Australian Friends of Armenians that became on of many organisations affiliated with the National Council of Women in New South Wales in 1930. Her fund continued to operate through the Second World War.

The first Armenian genocide refugees migrated to Australian in 1924, numbering perhaps 100. Post–World War II about 500 had arrived by 1960. The establishment of Armenian churches in Sydney and Melbourne, and the Australian government opening up Armenian migration for those fleeing the Middle East turmoil in 1962-63. The Lebanese civil war of 1975 and the 1979 Iranian revolution saw the number of Armenian migrants (from 43 countries, 25 nationalities and speaking 35 languages) swell to 10,000. Subsequent overseas conflicts, as well as friends and relatives already, here has lifted Australia’s Armenian population to approximately 50,000.

[Two of our best-known Armenians are the current Ambassador of Australia to the United States, Joe Hockey (whose father Richard Hokeidonia changed his name to Hockey after arrival in 1948) and New South Wales Premier Gladys Berejiklian, whose grandparents were orphaned by the Armenian Genocide in 1915. She spoke only Armenian until five years old, when she began learning English. Gladys has remained involved in the Armenian-Australian community, serving a term on the Armenian National Committee of Australia. In 2015, she attended a commemoration ceremony in Yerevan for the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide.]

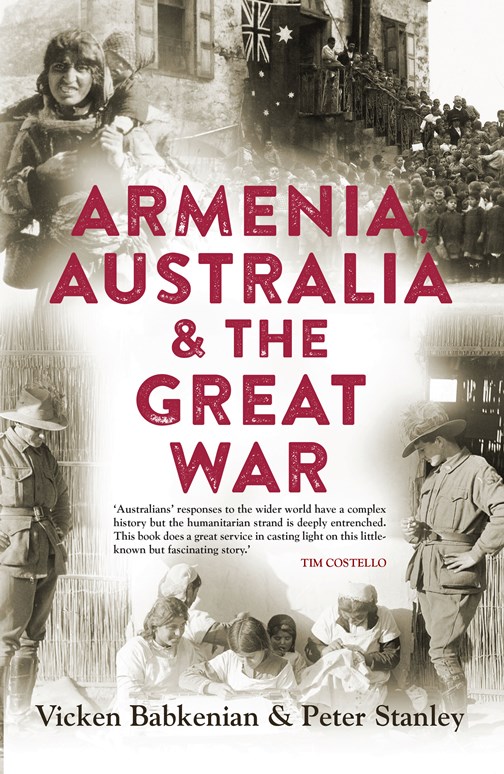

Vicken Babkenian, an independent researcher for the Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, has meticulously researched the background to this work. His co-author, Peter Stanley is a research professor at UNSW Canberra and president of Honest Truth, was pressured prior to publication by Australia’s Turkish Ambassador not to use the term ‘genocide’; one million deaths was more than sufficient justification for its use throughout the text. Stanley is critical of the manner that relations between Australia and Turkey have been built ‘upon falsehood and sentimentality, fictions, evasions and lies connived by both governments and many Australians heedless of the evidence’. He is not looking to alter our current good relationship with Turkey.

Included are a lengthy and comprehensive Bibliography, Notes and Index as well as two very clear maps and a collection of excellent photographs (from 1915 to 1923). This is a story that gets to the truth, and hopefully will lead to a greater understanding of the ordeal of the Armenians and a reappraisal of Australia’s relationship with them.

Reviewed for RUSIV by Neville Taylor, January 2018

Contact Royal United Services Institute about this article.