This short book is the product of Pat Beale’s interest in the Australian Imperial Force’s (AIF’s) performance in the First World War in Europe. Beale critically examines seven ‘legends’, or shibboleths, relating to the AIF through the lens of seven battles in which the Australian Corps fought during 1918. The seven legends he examines are shortened into the following popular terms: ‘sheep to the slaughter’; ‘a pointless struggle’; ‘Aussies, the born soldiers’; ‘stabbed in the back’; ‘fighters, not soldiers’; ‘lions led by donkeys’ and ‘loveable larrikin’. He notes that four are of Australian origin and three are foreign constructs.

Beale argues that the public, not the soldiers themselves, largely led the process of creating these legends. Because soldiers tend not to speak or write of their experiences, the public imagines and fills the space – sometimes simplistically. He additionally argues that the public filled this space with notions of soldiers needlessly suffering and dying amid horrifying circumstances. My sense is that, while there is some merit in this argument, it is in itself overly simplistic and many factors inform, shape and evolve the historical record and perceptions over time.

Surprisingly, in making this argument, Beale ignores the Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 which is arguably one of the most detailed first-hand accounts of wartime events ever produced. As Peter Stanley once wrote: “It was written by men who had lived through the Great War, men who worked with a profound sense of the sacrifice that Australia had made in that war. They wrote from first-hand knowledge of those who had fought, in many cases having shared the experience of war. Bean himself landed on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, had been wounded in August, and had been present at practically every battle in which Australians participated on the Western Front. He wrote the two Gallipoli and four Western Front volumes, the heart of the enterprise.” The fact that the twelve volumes of the Official History were published between 1921 and 1942 and tens of thousands of individual volumes have been printed, suggests that these have been a very significant contributor (notwithstanding some acknowledged limitations, flaws and omissions) to the public’s knowledge and understanding of the war – as they were also to the soldiers who participated in the war and only had a personal perspective.

Beale’s book is a little reminiscent Anzac’s Dirty Dozen: 12 Myths of Australian Military History edited by Craig Stockings and published in 2012. While Stockings – a noted historian who now leads the production of the next tranche of official histories – and his contributing writers critique over-simplification, jingoism and exaggeration with facts, Beale moves in the other direction and contends that the Australian Corps’ successes are underappreciated and that its “achievements have been trivialised”.

The correlation and causation between Beale’s seven legends and his main contention regarding the performance of the Australian Corps in 1918 is tenuous and thin. That the Australian Corps in 1918 was a capable and experienced fighting formation is, based on the available evidence, probably a fact. John Monash and other Australian chroniclers have not unsurprisingly praised the performance of the formation (Monash arguably a little too vigorously), but a completely objective assessment remains elusive. Like most wars, the participants can similarly feel both elated at their perceived tactical successes and saddened by the death or wounding of comrades – these are simply two sides of the same old coin and Beale has not discovered anything new here.

Beale’s publisher asserts that “an ex-soldier [he] uses his military background to help re-discover why and how the [Australian] Corps was so successful and also the reasons their triumph has been ignored”. Notwithstanding Beale’s distinguished service, his arguments in support of his main contention are not sufficiently robust; he does not, for example, critically assess the Australian Corps’ performance in 1918 relative to other British Expeditionary Force formations, or how much the German Army’s collapse from August contributed to the Allied ‘triumph’; nor does he address how perceptions – Australian and foreign – of the Australian Corps performance may have changed over time.

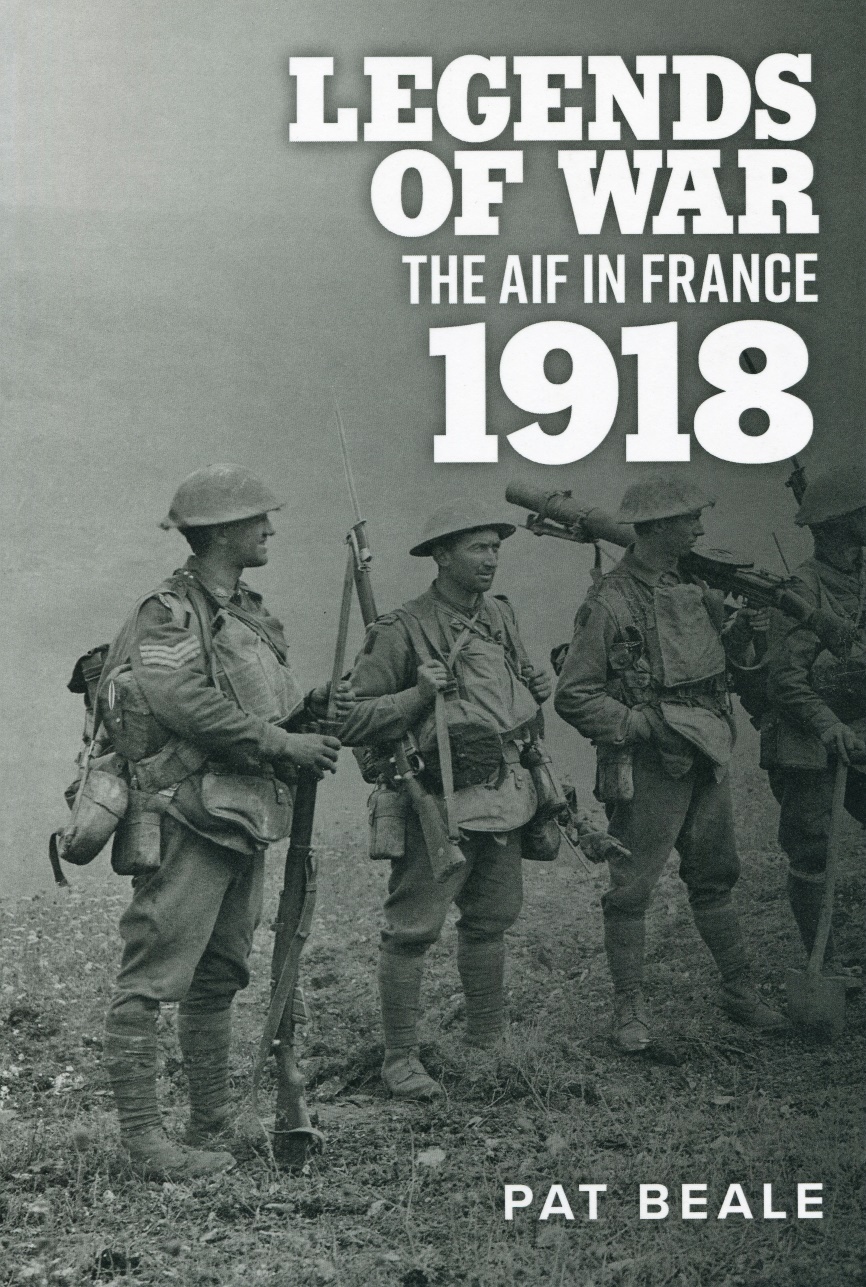

Legends of War includes a number of black and white images throughout the book, three maps, end notes, a bibliography and an index.

Beale served as an officer in the Australian Regular Army for thirty years during which he saw active service in the Malayan Emergency, the Confrontation in Borneo where he was awarded a Military Cross, and as a member of the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam where he was awarded a Distinguished Service Order for gallantry and a United States Silver Star for his role in the battle of Dak Seang. Beale retired to the Adelaide Hills and this is his first published book.

It is perhaps not surprising that after 100 years the performance of the Australian Corps in 1918 has become a topic of diminishing interest and subject to the vagaries of shifting perceptions over time; but, as a vehicle to raise public awareness of that performance on the occasion of the centenary, my sense is that Beale has missed the mark. Nevertheless, Legends of War is an atypical approach which will be of interest to some military historians.

Contact Marcus Fielding about this article.