The Balloon goes up: The start of the Tet Offensive: At 6 pm on 29 January the Tet truce came into effect, and operations by the Australians were put on hold. During the early hours of the following day, however, some communist forces in the northern half of the country mistakenly began their part in the planned Tet offensive a day early. President Thieu of South Vietnam immediately cancelled the ceasefire and at 3 am the next day the relative calm was shattered as towns and cities across the nation came under massive attack from the NVA and VC.

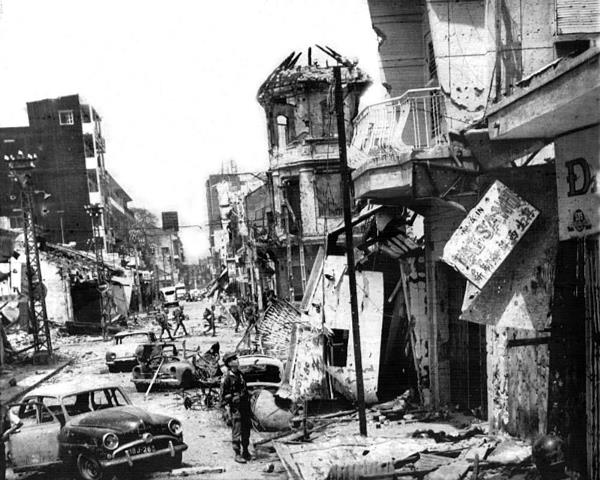

A particular focus of the offensive was Saigon, the population of which was sent reeling by an onslaught which was both frightening and staggering in its savagery and destructiveness. Soon large tracts of Cholon, the adjoining Chinese town, were leveled by fighting between enemy and government troops.

The Australians were called upon to deal with a Viet Cong Tet incursion into the village of Trang Bom. D Company of 2RAR, supported by 3 Cavalry Regiment armoured personnel carriers, became involved in house-to- house fighting to clear the village, only to see the Viet Cong return the next night and cause the whole process to be repeated. Fighting there lasted into 2 February.

3 RAR at Anderson: According to English in Brave Lads, MAJ Geoff Cohen 2 I/C 3RAR, was put in charge of the defence of FSB Andersen, and “had approximately 500 troops under his command and dug in at the FSB. His force comprised a troop of APCs, two mortar tracks …from A Sqn 3 Cav and a Troop of Engineers from 3 Troop 1 Field Sqn.” (p.123) and “One area of concern to Major Geoff Cohen was a knoll situated outside the perimeter. The knoll was undefended, but with his typical efficiency, Major Cohen insisted that it would have to be covered. He decided to reinforce that part of the perimeter with extra claymores. He also left instructions for a small standing patrol to be positioned on the knoll to give early warning in the event of an attack – Engineers provided men for the patrol.” (p.124).

The first Section strength standing patrol provided by the 3 Troop Engineers was on the night of 16/17th February and, after the toss of a coin, was provided by 10 Section under CPL Frank Sweeney and included Sappers Norm Cairns, Vic Underwood, Chuck Bonzas, John Hoskin and Brian Hopkins.

LCPL Barry Swain of the 3RAR Antitank and Tracker Platoon recalls (2016) “On the 17th we were warned out by LT Colin Clarke that it was our turn to go out to the knoll and got ready with ammunition, radio etc. The Section commander was CPL Dan Shine, with LCPLs Hans Vanzwol and Barry Swain, and Privates Bruce Critchlow (M60) Ron Cruise, and Giuseppe Lacava. Then about 1700hr we were stood down and told that Engineers were to provide the patrol that night….”

Lieutenant Peter Perry, the Engineer Troop Officer, was alarmed that his men were being sent out to the knoll: “Suddenly without warning … I was advised that we were to provide the standing patrol … Why … not Infantry? Apparently they needed a rest and anyway ‘Engineers can fight as Infantry’. A heated argument ensued as I pressed for answers to some fundamental requirements such as:

a. reconnaissance?

b. detailed orders as opposed to ‘you’re doing it tonight’?

c. a briefing from those who had gone before?

d. making an informed plan?

e. selection and briefing of the participants?

f. Rehearsal?

g. How would the patrol’s harbour location be transmitted to the command post?

h. What action was to be taken on enemy contact?

No win for me and little time left to walk to the knoll. I took command of Corporal Dave Cook’s Section as Cookie was ill having being bitten by a scorpion, and I had been trained as an infantry Platoon Commander. Our (CMF) Staff Sergeant Colin McLaughlin (Mac) argued that it wasn’t an Officer’s job to command a section and anyway, he had been a Minor Tactics Instructor at the Jungle Training Centre at Canungra. Mac asked our boss Captain Viv Morgan to decide, and he got the nod, not me. The next time I was to see Mac was in the morgue at Long Binh the following day. There go I except for the power of the short straw.”

Note: Peter Perry’s account “FSB Andersen- Operation Coburg: The First Fight of the Trilogy, The Untold Story” (2016) has been distributed on Veteran networks.

So, the patrol set off before dark for the knoll, and in plain sight of the villagers of Trang Bom, not that this mattered as the enemy had known for some time where the listening post was located. The patrol comprised ten men: Staff Sergeant Colin McLaughlin age 38, the radio operator Lance Corporal John Garrett age 20, Sapper David Steen age 21, Sapper Allan Pattison age 19, Sapper Geoff Coombs age 22, Sapper Vince Tobin age 24, Sapper (later LCPL) Murray Walker age 22, Sapper Robert Creek age 22, Sapper Jack Lawson age 18 and Sapper Lyndon Stutley age 21.

Survivor Sapper Robert Creek remembers: John Garrett had been instructed to ‘radio to base .. any activity that we observed or experienced’.. then return to the Base .. through the American sector as soon as practicable’ .. John had a signal torch, red and green lenses to enable the Americans to identify us. We were heavily armed; my mate Jack Lawson carried the M60 machine gun, with me as his offsider. I had never been so heavily laden in my life: a hand grenade in each top breast pocket, seven SLR magazines of 20 rounds each clipped to my belt, a continuous metal belt of machine gun rounds over my shoulder down to my thigh, a claymore mine complete with detonators, wire leads and hand generator, plus my rifle.

At the pre-determined location among the banana trees we lay in a defensive arc, in pairs, waiting, listening, in silence, very tense, with the sounds of the night surrounding us. Nine o’clock, ten o’clock, eleven o’clock. Time ticked away very slowly. We dozed on and off and, apart from the annoying buzz of mosquitoes; all we heard was the occasional suppressed whisper of a mate. Still nothing happened.

Back inside the Base, 12 Section Sappers Norm Cairns and Vic Underwood were manning the 3 Troop M60 machine gun on top of their gun bunker on the perimeter, waiting and looking out into the dark. Back from the perimeter, LT Peter Perry was sitting on the top of his bunker with CAPT Dick Lippert, the 3 RAR Doctor, again waiting and watching.

Meanwhile, in the 3 RAR Command bunker, a message was received that enemy activity could be expected early a.m. on the 18th. A coded message from Hanoi had been intercepted, ordering the communists in the south to launch an attack at 0300hr on the 18th. Intelligence also indicated that the VC had distributed 3 tons of ammunition among their units, had in the Bien Hoa area conducted propaganda talks, and that Saigon shipping companies were refusing to work on the docks on the 18th. It was suggested that ‘this information be called to the attention of the commander’.

So, the stage was set for the first of the enemy assaults on the Base.

The first attack on the 18th was preceded by a heavy rocket and mortar barrage on the base in the early hours of the morning, followed by two waves of VC infantry each of company size. This attack focused on the south-west of the perimeter manned by 3 RAR’s echelon and mortar platoon, as well as an American medium artillery battery. The perimeter wire was subsequently breached, but the attack was repulsed by mortar counter-battery fire, Claymore mines and the heavy weight of machine-gun fire from armoured personnel carriers and the American gunners. The communist mortar bomb barrage had had a devastating effect, falling among the American and New Zealand gun positions, the 3RAR mortar lines and the battalion echelon, as well as scoring a direct hit on the Australian Engineer standing patrol.

Ian McGibbon (in New Zealand’s Vietnam War: A history of combat, commitment and controversy 2010): “The gunners had settled down for the night. About midnight Battalion Commander Jim Shelton and Battery Commander Tony Martin were ’sitting in the CO’s tent admiring the stars and sipping – coffee when a green signal flare arced ominously across the base. At 1am a shower of mortars and RPGs heralded the first of two assaults on the base by a determined enemy force. Mortar bombs fell on the Australians then ‘walked’ across the base and onto the standing patrol, which, caught in the open, suffered serious casualties.

Five minutes later another green flare went up, and Viet Cong waiting behind a paddy bund to the south- west surged forward against the US Battery, the mortar platoon and the unit echelon area. After hurling grenades, they penetrated the wire and managed to get into a gap between the mortars and the American battery. Although this presented some difficulties in bringing fire to bear, the attack was halted by machine gun fire. The second assault, both north and south-west, was halted in front of the wire. This was followed, after a brief respite, by another barrage on the American and New Zealand gun positions.

About 150 mortar bombs landed in the firebase during the two-hour action, inflicting considerable damage on three American 155mm guns and vehicles and Australian APCs. Although none of the New Zealand gunners was injured, 3RAR was not so fortunate, losing 8 men killed* and 25 wounded………the deficiencies in the firebase defences having been starkly revealed, next day ‘the digging was furious’. “

*McGibbon counted the four Engineers as part of 3RAR troops

LT Peter Perry: About midnight a green flare was fired from the south west of our position in fairly close proximity to where our patrol was located, As nothing further eventuated within the next 40 odd minutes and after a radio check with John (LCPL Garrett) I hit the pillow…. when all of a sudden the first two enemy mortar rounds were launched. All hell broke loose …. we began receiving RPGs and machine gun fire followed by two ground assaults primarily against the US guns.. The enemy mortar bombs were cleverly walked through the base from east to south west passing beyond our perimeter and through to our standing patrol position.”

Sapper Norm Cairns: After the green flare went up we were all on tenterhooks. Then all of a sudden we heard the pop of the primary charges and the first enemy mortar bombs dropped into the base well back behind us. Vic Underwood and I had climbed to the top of our bunker to see if we could locate where they were being fired from, when our field telephone rang. Vic answered it. ‘I think we are being mortared’ said the officer on the other end of the line, stating the bleeding obvious, just as one of the bombs landed virtually under our feet at the foot of our sandbag wall. We were immediately knocked back by the blast wave; arse over head, but luckily the sandbags took the shrapnel.

Sapper Vic Underwood: We were shaken up but, with ears ringing and dust and leaves swirling around us, somehow alive, and I still had the telephone in my hand. Norm Cairns: In the best ANZAC tradition Vic gets up and with the telephone still in his hand and with his dry sense of humour replies: ‘You THINK we are being mortared Sir!. Sir, I can tell you for absolute fucking sure that we ARE being mortared!’ and we both pissed ourselves laughing, for which we were later given a dressing down. Vic Underwood: Our thoughts soon turned to defence and turning back any frontal attack. Norm and I got in behind the M60 and flicked off the safety catch; we picked up the source of an enemy heavy machine gun out in the night and brought our M60 fire onto it. After we had fired about 1 ½ belts the enemy gun fell silent.

Sapper Robert Creek (at the listening post): About midnight came a small popping sound as the enemy set off a green flare, high in the sky, high above the Fire Support Base. It hung like a bright green lantern for what seemed a very long time, lighting up the whole base – tents, store bunkers, the artillery, helipad, sentry boxes and razor wire fencing, all against a blackened night sky.

The enemy had set up a mortar base on the hill behind us and fired over our heads to the other side of the base. At least two perimeter sectors of the Base were under attack. The night crackled with small arms fire and the explosions of grenades, the noise deafening like a tropical thunderstorm but with deadly lightning strikes of rifle fire and light and heavy machine gun fire, and RPG and mortar shells exploding and peppering the air. The sky lit up like day as flares from the base burned underneath their cotton canopies as they floated down to earth over the jungle. The Viet Cong mortar crew lifted their sights and lobbed their projectiles with great accuracy, as their mortar explosions cut a path of destruction across the FSB, each explosion coming closer to us.

Ian McGibbon: Woken by the noise, LT Harvey sprinted to his command post…. and soon had the gunners sweating over their guns as they engaged the suspected site of one of the two enemy mortar base plates detected; the other was too close to the standing patrol. When he tried to bring in outside artillery fire, he found none available – enemy probes on other firebases were obviously designed to prevent such support.

LT Peter Perry: Our radio operator told me we had lost contact with the standing patrol after the mortar barrage but I kept on trying to contact them during breaks in the fighting and whenever I could get on the command radio network. No response came.

Sapper Robert Creek: Then all of a sudden a massive explosion deafened us as shrapnel flew and cries of intense pain filled the air. Banana trees fell amongst us. The enemy mortar crew had scored a direct hit on our position and before we could recover from the shock, another round exploded behind us, smashing and crashing more banana trees. The enemy mortar crew were still adjusting their sights and firing.

With ears ringing and mates calling for help, we yelled back and forward to each other. Two didn’t reply, Sapper Allan Pattison, a popular bloke from Kadina S.A., and Sapper David Steen from the Falklands; they were gone quickly, and we thank God for that. SSGT McLaughlin followed them some time later.

The young Lance Corporal John Garrett called out to the sergeant but he didn’t answer. John became concerned and called out to us ‘are you all right?’ As his pain got worse he became delirious and his voice weaker. He was still wearing bits of the radio that hadn’t been blown away. His main concerns were for us; He was a real soldier – concerned for his mates despite his mortal wounds. We called to him, offering the only thing we could – reassuring words. We hoped that the VC couldn’t hear his cries over the noise of the battle for I am sure that, if they had, I would not be here today.

Small arms fire continued to crackle, interspersed by light and heavy machine gun fire. A helicopter gunship swept very low over us, its search beacon sweeping the jungle fringe. Bullets with tracer spat from its sides, and flames spat out of pods as underslung rockets were fired and exploded in the jungle below.

There then came a dramatic lull, a few minutes of spasmodic firing, then silence. The battle stopped as quickly as it started. A lone bird made a mournful cry in the silence that filled the approaching humid dawn.

Next to me, Sapper Jack Lawson called out in pain as he tried to turn towards me, a piece of shrapnel ripped into his hip, unnoticed until then by himself as he went about his duty. I quickly went to his assistance, grabbing at the field bandage taped to the butt of my rifle, but my left arm collapsed under me. I too had been hit but didn’t know it. We applied bandages to each other and reassured each other that we were OK.

Meanwhile, Sapper Murray Walker and a mate who had not been wounded, crawled across and told us of the injuries inflicted on the others; two had worn the full force of the explosion, their organs exposed and bodies lying in acute angles of repose and covered in blood.

We quickly decided to get word back to the base. Murray and a wounded but insistent Jack set off immediately, running from cover to cover and using their instinctive bushcraft skills, equipped only with their rifles and a few magazines of ammo. They soon crawled into a clump of scrub relatively close to the wire gate they had exited to commence the patrol the evening prior. About the same time as the dawn made a slight hue in the eastern sky, Johnny Garrett, the Regular Soldier with the one stripe, cried out for the last time and took his leave of us.

At the wire gate which he knew was booby trapped, Murray called out loudly to the Americans, identifying himself as an Australian soldier. A southern drawl was quick to respond, thinking it was a deception by the VC. “Show yourself or we shoot” said the American, and with great anxiety the two Aussies stood up then ran at the coiled Dannet wire, clearing it with ease.

LCPL Barry Swain 3 RAR: We all vividly remember after the attack the two Engineers yelling out loudly “we are Aussies and we are coming in”, over and over again until they were behind the wire: It was dark and not long before stand to on the morning of the 18th. Dan, Hans and myself shiver to think that it could have been our group who were decimated; the memory will be with us forever.

Sapper Robert Creek: Once inside the base, the two Sappers were taken to the 3 RAR Command Post and interviewed by MAJ Ian Hands and also LT Perry RAE. Jack was immediately sent to the Regimental Aid Post for treatment of his wounds, while Murray Walker was asked to lead an infantry platoon back out to the knoll to recover the remainder of the Engineer section, living and dead.

Michael English: “Lt Harry Clarsen’s 3 Platoon A Company led the patrol out to bring back the engineers bodies: The flare aircraft was so up there, casting this eerie light tho seemed to suck the colour out of everything. We were guided out by one of the survivors [SPR Murray Walker] who had managed to crawl back through the American gun position. It was not a pretty sight.

Corporal Jack Davies, the A Company medic attached to 3 Platoon went out on the patrol to recover the dead engineers. He later recorded “as I moved into the position I felt that I was in the killing ground of a perfect ambush site. The patrol had received a direct mortar or RPG hit as well as possibly small arms fire.” The patrol quickly formed a perimeter and located the engineer’s bodies and was greeted with a scene of devastation. After a short time the patrol moved back to the FSB, carrying the dead and their equipment.”

LT Harry Clarsen recalls (2016): “as we went out in the night to recover the Engineer patrol, my main fears were not of the enemy, but the Americans; their idea of a clearing patrol was to brass everything up for ten minutes outside of their perimeter with all the firepower they had. Unlike us they never actually sent anyone outside to have a look to see if any enemy were about. The continuing eerie, ever changing light from the Snoopy flares, in my mind, only served to make us better targets for the Yanks. My Platoon Sergeant John Hoffman organised the recovery of the bodies of the Engineers onto the stretchers, while I was keeping a very anxious eye on the surrounding scrub for any signs of enemy presence. My anxiety continued as slowly we moved back to the FSB perimeter with our heavy burden, but again my anxiety increased as we approached the American position. Would they be so spooked as to brass us up as we came back? Fortunately not, and it was then that I really appreciated the courage of the two Sappers who had earlier come back in through the American perimeter to report the destruction of the standing patrol.”

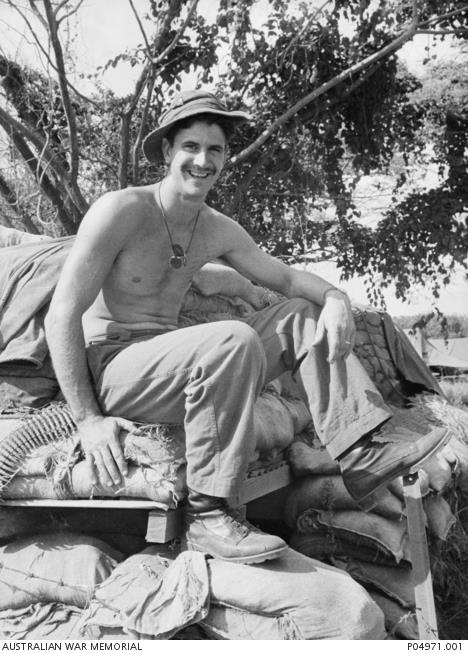

For his actions that night and later during Operation Pinaroo, Sapper Murray Walker was awarded a Mention in Despatches. Murray Walker’s Citation is published in full in Florence, pages 188,189

Sapper Robert Creek: From our position behind the fallen banana tree, Sapper Lyndon Stutley and I could hear a strange sound, a brushing, rustling sound. With the machine gun cocked and our rifles at the ready, we lay tensed, our trigger fingers quivering. Then at point blank range, directly in front of us, we heard a voice “Where are you?” …. it was Murray and the platoon of infantrymen come to gather us up and take us back to the base.

The four bodies were picked up by their clothes and carefully placed on two stretchers. One body on top of the other…. what else could be done? Their arms dangled lifelessly over the edges as the infantrymen took turns to carry the stretchers.

The sight of these squashed bodies of our friends, who were alive just a few hours before, was too much for me, and I doubled over, fell to my knees and started crying uncontrollably, letting my rifle fall to the ground …. to this day that sight of my deceased friends, just lying there in a dishevelled heap, is as clear as it was then and often brings tears to my eyes.

LT Peter Perry: I have no idea what the hour was when I crawled among the rest of our troops to deliver the devastating news. The dead were removed to Long Binh, where Cookie and I flew later that day to make a formal identification. The wounded were evacuated to Vung Tau from where Robert Creek was subsequently medivaced home to Melbourne. The others returned to Nui Dat.

Sapper Peter Macdonald*: In the early stages of Anderson I spent my time working with A Coy 3 RAR on standing patrols north of the FSB. I had two shell scrapes, one with 3 Troop and the other with 3 RAR. I would be informed late afternoon if I was staying with 3 Troop or heading off to A Coy. On the night of the first attack on Anderson I was on a standing patrol with members of A Coy. It was a moon-lit night and from our position we had clear 180 degree vision.

We had just settled down and within 10 minutes found ourselves in the centre of significant movement of VC. One group set-up approximately 30 metres from our position and commenced firing mortars into the FSB. There was nothing we could do without being heard or sighted. Radio contact was attempted to provide the VC position, but was unsuccessful, we just had to wait it out. When the VC had moved on we packed up and headed back to the FSB. On return to my 3 RAR position, the situation I was faced with made me fully realized the term “when your number’s up”. A mortar had landed alongside my shell scrape destroying it and killing an A Coy member in an adjacent bunker.

On my return to 3 Troop I was informed of the Engineers standing patrol and the loss of our four mates. In mourning our loss we attempted to rationalize the outcome, the situation was horrific but also surreal, and an issue that has haunted all of us since. Unanswered was that FSB Commanders were aware that VC and regular troops were in the vicinity of Anderson, yet small observation standing patrols consisting of inexperienced 3 Troop Sappers were sent out on the nights of 16/17 and 17/18 February.

* Note: Sapper Macdonald was deployed again after Andersen as a Combat Engineer attached to 3RAR on Operation Pinaroo in the Long Hai Mountains where, after a number of booby trap incidents involving Infantry, it was decided to use the Engineers in their role front of the Infantry to locate bobby traps and mines as the battle group advanced. The Combat Engineer role in these circumstances is to not only locate and deal with mines and booby traps while pushing forward, but also to act as an Infantry forward scout.

On the 15th March 1968, shortly after assuming the ‘Follow the Sapper’ position, Sapper Macdonald was caught in a VC ambush and suffered a severe gunshot wound to his right arm, after which he was ‘dusted off’ in a “hot extraction” by a US Army gunship to the Australian Hospital at Vung Tau. His wounds were so severe that he had to be medically evacuated home to Perth, Australia.

In loosing Sapper MacDonald, the Engineer Squadron lost not only a good Combat Engineer but also a good photographer; His camera tumbled out of one of his extra rifle magazine pouches during a contact and was probably recovered by the VC and sent to Hanoi.

Peter Macdonald was kept alive by the expertise of the 3RAR medic, Corporal Jack Davis and the Australian Hospital at Vung Tau. His situation might have been serious, but his thoughts were with two very close and special friends who had lost their lives. Close mates, Sappers Geoff Coombs and Vince Tobin, who went through the horrors of the standing patrol at Andersen, were both killed when they came into contact with a M16 mine in the Long Hais.

Peter Macdonald: I first met Geoff and Vince at SME during our Corps training and later in our 3 month stay in Holding Troop prior to being posted to 3 Troop 1 Field Squadron Vietnam. We became close friends and arriving in Vietnam we all shared the same tent and worked together.

After the decimation at Andersen, Geoff, Vince and myself discussed the issues. Understandably they were both traumatised and considered that they were lucky to be alive, but might not be so fortunate next time. After considering their families and friends back home, they approached Captain Viv Morgan for a transfer to the much safer 21 Engineer Support Troop, and this was granted. Unfortunately the transfer could not be completed until their replacements had qualified through the mines training room at 1 Field Squadron Headquarters, and, in the meantime all of 3 Troop, including Geoff and Vince, were deployed again in Combat Engineer roles detecting and disarming mines and booby traps on Operation Pinaroo.

Geoff and Vince were working together when they responded to a call for help from an Infantry patrol that had walked into enemy land mines a short distance from their position. Selflessly and courageously in their haste to respond to the calls for their assistance, they themselves came into contact with a freshly laid M16 mine on the edge of a new bomb crater, and they died instantly.

My memory of my two great mates has been with me ever since.

Sapper Norm Cairns: The Boss, Major Kemp, flew out to Andersen from Nui Dat that morning to see his sappers. I’ll never forget his opening words: “Tough night boys!”.

Ian McGibbon: When a Light Fire Team of Huey Cobra Gunships arrived, it initially misjudged the position and fired on 3RAR, amazingly causing no casualties in spite of 12,000 rounds a minute being unleashed on the Australians. The gunships then engaged the enemy’s mortars and forming-up place. Air support was also provided by a DC3 equipped with mini-guns, code named spooky but generally known to the troops as ‘puff the magic dragon’. It dropped flares to illuminate the position as well as using its firepower to lethal effect.

An extra infantry company was brought in, the communications were improved with extra radios, additional defensive fire support was installed and civilians were prevented from approaching the base. The work stood the defenders in good stead when, three nights later, the enemy attacked again, this time without mortar support. They were halted short of the wire in a two hour firefight. Yet another attack was forestalled on 27 February when quick work by the mortars and artillery broke up the attacking force before it reached the base.

Sapper Peter Macdonald: Following the tragedy of the standing patrol, military commanders (or someone) acknowledged the decision to use combat sappers as Infantry was a blunder and immediately increased the force on FSB Anderson with a further full Company from 3RAR deployed to the knoll site.

Former FO, now Colonel Mike Harvey RNZ Artillery (retired), recalls (2016) During the night of the attack I deployed a Douglas AC47 (DC3) Spooky known as Puff the Magic Dragon … which had three 7.62mm miniguns and flares. I would indicate the target (mortar base plates) and Spooky would engage its guns. Even with the tracers spaced apart, the fire looked like a stream of red water from a hose. The aircraft also assisted by dropping a flare which lit up the battlefield like day. Spooky would then circle the FSB, firing at the designated targets and when it reached the starting point, drop another flare.

The FSB was a bulldozed rise and well dug in – the CP and our sleeping quarters being significant holes in the ground presumably dug by the engineers. I must confess I don’t recall any deficiencies (at Andersen) as such.

My main problem as FSB FO was the inability to engage artillery during the 18 February attack because we had lost communications with the engineer standing patrol. Without communications we did not know if the patrol was moving across the battlefield in front of the FSB in an attempt to get back in and if they were, in what direction. In retrospect, it does seem strange that the engineers provided the standing patrol. I would have thought this would normally have come from the company providing defence for the FSB.

The other problem was the US gunship that strafed the FSB. No one knew who it was or how it came about but there were no casualties and it happened only once.

Sapper Chuck Bonzas: When the American Huey gunship fired on 3 RAR, it flew across our position on the base perimeter and showered us with thousands of red hot cartridge cases, so hot that they burned holes in our packs. Perhaps the Yank pilots thought that the VC were inside the wire and had taken the 3RAR position, or perhaps they were just bad at finding the correct target.

Click here to read Part 1

Click here to read Part 3

Contact MHHV Friend about this article.