Logistics

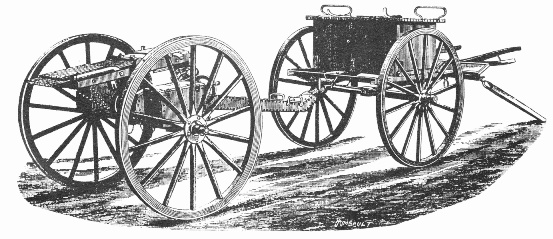

Exercises like this, small in scale and time by Easter camp standards though it was, still required considerable logistics – rations had to be arranged and issued to the soldiers to carry in their haversacks or ration carts pre-positioned in the exercise area, medical arrangements had to be made in case of exercise casualties, and uniforms and equipment had to be checked so all was in readiness. Blank ammunition had to be supplied including for the foot-soldiers’ Martini-Henry rifles (20 rounds each in pouches), the Nordenfelt quick-firing (50 rounds each) and the field artillery guns (15 rounds). For Red Force, the Assistant-Commissary-General the Hon Captain James McCallum’s [1]department supplied two ammunition carts and two pack horses with ammunition boxes, with 7000 rounds in each cart, and four water carts – one ammunition cart, two pack horses with ammunition boxes, and two water carts to Spring Vale station, and one ammunition cart and two water carts at Oakleigh.[2]

It was not just the Ader Telephone which was a new military application in the ‘Battle for Oakleigh’. For the first time, ‘khakee’ (khaki) helmet covers were worn, leading to amused comments by the civilian journalists:

‘There are many eccentricities in military uniforms, but this beats the record, in this colony at least. The combination of brown khakee with the variously colored suits was utterly inconsistent, and the members of the force must not be surprised if remarks are made about their patchwork appearance.’[3]

At the same time, it was recognised that it might even be necessary to get a ‘full khakee suit’ to match the helmet, and then perhaps ‘practical military principles may bring about the abolition of the helmet itself in favor of a soft hat’.

Before the ‘battle’ could get underway, communications and exercise umpiring were put in place. Signallers from the units of Blue Force reported to Major Rhodes and from Red Force to Lieutenant Colonel Templeton while the umpire staff were assembled. The commanders of the protagonist forces each sent in a copy of their plans for the attack and defence beforehand so that umpires could anticipate the action and observe accordingly. The umpire’s staff wore white bands round the left arm – among other things the amount of smoke generated from 19th century firearms and artillery added to the need for some visual distinction. Colonel Brownrigg, the Victorian Commandant [4] was umpire in chief, supported by four umpires, namely, Colonel Thomas Bruce Hutton,[5] Lieutenant-Colonels Alfred Freeman and Peregrine Henry Thomas Fellowes and Major Henry James King, with the awkwardly named Lieutenant Charles Myles Officer acting as assistant umpire.[6]

![Colonel A Freeman [7]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK19.jpg)

![Major H J King 1888 [8]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK20.png)

Almost all was ready to start – on the firing in quick succession of two rounds by a field gun – but first the VIP observers needed to be catered for. Normally an exercise of this kind would be watched by perhaps several hundred people, but ‘owing to the many sporting attractions nearer town’ the ‘exercise did not bring together quite as many sightseers as usual’. However, His Excellency the Governor of Victoria Sir Henry Brougham Loch GCMG KCB, Lord Hastings (George Manners Astley, 20th Baron Hastings) and General John Studholme Brownrigg, the father of the commandant, who was visiting Victoria at the time, drove down early in the day to watch the exercise.[9]

![Governor Loch [10]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK21.jpg)

![The Governor’s guest, General J S Brownrigg [11]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK22.jpg)

Mounted Rifles were sent forward by Lieutenant-Colonel Price to patrol towards Spring Vale, and worked the country for a kilometre or so to the front of the outposts on Clayton’s Road – apparently ignoring the instruction for defenders not to move south of that road. There was some delay in the movement of the attacking force from Spring Vale and the opening signal guns were fired an hour late. Undeterred, the attacking force made a feint on the western approach with the main attack coming from the eastern side on the ground closest to the railway. The infantry feint – the 1st Battalion – came through some paddocks until they lined the first rising ground, and there lay down till the artillery came up. Its arrival masked by the timber in the centre ground, Major Ballenger’s battery went round by the Dandenong-road and unlimbered, getting away several shots from almost a kilometre away before the defender’s artillery could reply.[12]

The defending redoubt being attacked was rudimentary but strong – the engineers had worked from 5 am to dig in the six guns and observation points had been placed forward connected back with telephone wire. And as a last resort, there were the six mines in place forward of the redoubt. Nonetheless, once it was determined that the redoubt had been sufficiently ‘softened up’, a half battalion of infantry under Major Robertson was sent forward along the road, fighting with the defending Engineers up to about 370 m. During this advance they were exposed to a strong fire without cover, and were met by both machine gun fire from the Nordenfelt guns and infantry fire from the Engineers, sweeping the whole road. Nevertheless, they came on up the road regardless of circumstances.

![Skirmishing [13]](https://www.mhhv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/AK23.jpg)

The main attack now closed in on the redoubt:

‘Just at the last moment, as the enemy crowned a piece of rising ground opposite the redoubt, and from which it might be assumed they would attempt to storm the position, the line of ground mines was exploded, and the enemy had an idea of the fate that would have befallen them had they rashly advanced. Although only 12lb of powder were used for each charge, a mass of earth was thrown by the explosion a hundred feet or so into the air, while in one case a sapling, that had been lying near one of the mines, was sent hundreds of feet aloft, portions of it as large as a bottle, and snapped clean across, falling within a few feet of the men in the redoubt.’[17]

The fight was now stopped by the bugle call to cease fire. With the second battery late into action, the defending artillery was not silenced before the infantry attacked, and so the attack was judged to have failed (no-one talked about the mines). The troops lunched and horses watered. The officers messed in Oakleigh village, very likely visiting the Foresters Arms Hotel on the Broadwood as the only ‘salubrious’ public house there.[18] The feeding arrangements for the cadets were especially remarked upon, ‘each boy being supplied with a bag, containing a liberal supply provided by Mr. Straker.’[19] The troops were then paraded in review and inspected by His Excellency the Governor, accompanied by his guest General Brownrigg. The day was judged both ‘useful and inexpensive’[20] – all troops involved then returned to Melbourne by train or route march.

Conclusion

Later, on 24th November 1888, Colonel Brownrigg issued a general order commenting on the exercise at Oakleigh. He said that the defence had been well-planned although he thought the Nordenfelt battery could have been used in more forward positions. He was pleased with the small detachment of the Mounted Rifles which had ‘performed its scouting duties most admirably’. He also praised the work of the engineers for the well-planned redoubt and shelter trenches and the ‘great intelligence’ in the way the lines had been laid down by the Telegraph Section. He thought ‘C’ Battery of the field artillery had ‘turned out smartly’ and that the Senior Cadets had been ‘steady on parade and performed their drill very creditably’.

Colonel Brownrigg commented the attack was also well-planned with ‘A’ and ‘B’ batteries taking up their positions well, but criticised ‘B’ Battery for being ‘too much inclined to advance without proper support of infantry’. Again, the attacks by the 1st and 2nd Battalions had been carried out well, but the 1st Battalion ‘did not take as much advantage of cover as they should have’. The Ambulance Corps were ‘turned out smartly’, but its strength on parade was ‘unsatisfactory’.[21] The Commandant’s comments seemed to confirm general opinion that Templeton’s Red Force had been defeated by Price’s Blue Force and no doubt there were many conversations about conclusion that in the Naval & Military Club, NCO clubs and Other Rank canteens and public houses frequented by riflemen and Militia as the Militia forces geared up for the annual Victorian Association rifle matches in December to round out and complete their busy year.

The ‘battle for Oakleigh’ in October 1888 was a useful training exercise – cheap to run, conducted on actual ground which an invader of Melbourne might be expected to use if approaching from Westernport, and using the various arms and services in combination. Some equally useful ‘innovations’ were tested – wire telephones, khaki hats, mounted rifles, ambulance service, ordnance and commissariat. Many of the Militia officers engaged held prominent positions in the colony’s social and business life and some would continue military careers well into the 20th century – with a number of them as well as numbers among the soldiers who exercised that day, to see active service in the Anglo-Boer War, just 11 years away.

As for the village of Oakleigh, it no doubt returned quickly enough after the ‘excitement’ to its rural and newly industrialising state, but one wonders how much the exercise of 1888 encouraged young men of the district to volunteer for Militia or cadets. It was perhaps no coincidence that an Oakleigh Detachment of ‘H’ Company, Victorian Rangers was established in 1891 and a cadet unit re-established at the Oakleigh State School in 1894 after it had been disbanded just a year before the 1888 exercise. Militia, or as they are now called – Army Reserves – still serve in Oakleigh Barracks to this day.

[1] McCallum – appointed Deputy-Assistant Commissary-General with relative rank of Captain VGG 5, 15/1/1886, p51; promoted to Hon Major, and Assistant Commissary-General VGG 1 4/1/1889, p8; Ordnance, Commissariat and Transport Corps formed 1886 – VGG 104 24/9/1886, p2726.

[2] The Age 27 October 1888, p18 and 10 November 1888, p11.

[3] The Age 10 November 1888, p11

[4] Brownrigg biography – https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The Dictionary of Australasian Biography/Brownrigg, Major Henry Studholme.

[5] Hutton – a Crimean War and Indian Mutiny veteran who had retired from the British Army and settled in Dandenong, but was recalled to duty in the Victorian Volunteers and then Militia. In 1882 he had been acting Commandant in Victoria – Obituary in the Australasian, 24 October 1914, p30.

[6] The Age 10 November 1888 p11. Freeman, a contemporary of Templeton and an insurance adjuster, joined the Volunteer Rifles in Melbourne in 1859 – he was later President of the Naval & Military Club in Melbourne for 21 years. Obituary in the Argus 17 July 1916, p6. Fellowes – a seconded British Army officer for the permanent staff when the new Militia was formed, Fellowes later died in England in 1893 aged 42 “from the effects of injuries received when stopping a pair of runaway horses, thereby saving the lives of the occupants of the carriage to which they were harnessed” – Punch 17 Dec 1908, p26. Obituary – the Age, 4 December 1893, p5. King – joined the Victorian Government Railways in 1861 and became travelling auditor and adjuster of claims – the Australasian 7 March 1908, p39. Joined East Melbourne Volunteer Artillery in 1869 and rose to be Lieutenant-Colonel retiring in 1893 – VGG 10 March 1893, Issue 40, p1277. Melbourne-born King was a member of the Victorian Rifle team which competed at Wimbledon in England (as individuals) and then joined the NSW team to compete in the first ‘Palma’ competition in Creedmoor, USA in 1876 – Corcoran, J. E., The Target Rifle In Australia, 1860-1900, New York, 1995, pp97-118. Officer – eldest son of father of same name who prominent in social business and civil circles. Held various staff jobs including aide-de-camp to the Governor, Adjutant Field Artillery Brigade, Staff Officer Militia and Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General before joining reserve of officers in 1895 as Major. Sold up in Melbourne November 1901 to go to South Africa after missing selection for a contingent, may have served on Lord Robert’s staff before becoming a district commissioner in the Cape Colony. Returned to Melbourne 1907 and died unmarried in Healesville in 1910 after a long illness – VGG entries and Punch 31 March 1910, p24. In a serendipitous connection to Oakleigh, Officer’s Aunt, Mrs Suetonius (Mary) Officer was a member of the committee of management to establish the Melbourne Convalescent Home for Women established in Palmer Street, Oakleigh in 1886. She was still on committee as vice president when it relocated the Convalescent Home from Oakleigh to Clayton. She was present at the opening at Clayton in 1889 by the Governor of Victoria, Baron Loch. Lady Loch was the Home’s ‘patroness’. The former Home is now located within the Monash Medical Centre and known as McCulloch House [courtesy H G Gobbi].

[7] Perry, W., The Naval and Military Club, Melbourne 1981, fp65.

[8] The Australasian, 7th April 1888, p741.

[9] The Argus 10 November 1888, p13 and the Age 10 November 1888, p11. Loch – Governor from 15 July 1884 – 15 November 1889. See http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/loch-henry-brougham-4033/text6407, published first in hardcopy 1974, accessed online 27 March 2017. Hastings – a notable breeder of race horses in England, had visited his brother in Sydney before attending the 1888 Centenary Melbourne Cup on 6th November. Presumably he accompanied the Governor to Oakleigh as an opportunity for a ride and to see something of the country. General Brownrigg, C.B, was a former Grenadier Guard and a veteran of the Crimean War.

[10] Henry Brougham Loch, by unknown photographer, c1888 – La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria, H5425.

[11] Engraving by D J Pound of Colonel Brownrigg, C.B. from a photograph, in The History of the War in Russia: Giving Full Details of the Operations of the Allied Armies, London, 1855.

[12] The 12 pounders could fire their shells and hit a target ½ m wide at over 900 metres.

[13] Victorian Infantry at work, unknown newspaper c1888.

[14] The Argus 10 November 1888, p13 and the Age 10 November 1888, p11.

[15] The pole broke away at the footboard. The gun was kept in action as long as possible, and then abandoned on being rendered useless by withdrawing the springs. The Age 10 November 1888, p11.

[16] From ‘Engineering No 39, January-June 1885’, in Galloping Guns, p.152.

[17] The Argus 10 November 1888, p13 and the Age 10 November 1888 p11.

[18] Still trading today, since 1864. Named after the Foresters Lodge of the Ancient order which met there from 1861. Gobbi, H.G. Taking Its Place, Melbourne 2004, p40.

[19] C D Straker of the Three Crowns Hotel in West Melbourne was highly regarded as a public caterer. The Age 10th November 1888, p11.

[20] The Age 27 October 1888, p18 and the Argus 10 November 1888, p13.

[21] The Argus, 24th November, 1888, p9.

Contact Andrew Kilsby about this article.