Renfrew, a noted military historian and war reporter, has written a masterly history of a sparsely recorded period of the Royal Air Force between the First and Second World Wars. It is based, in part, on research at a number of institutions including the Royal Air Force Museum, the Imperial War Museum, the National Army Museum and the National Archives at Kew.

After the First World War large sections of the British public and certainly the Army and Naval hierarchy viewed the RAF (newly-formed from the Royal Flying Corps) as unnecessary, should be disbanded, and the much-reduced air assets parceled out between the Army and the Navy. Hugh Trenchard fought hard to save the RAF. Fortunately for the defence of Britain in the next World War he succeeded.

Britain had a major problem post WWI policing and retaining its Empire. The RAF, together with Churchill and other experienced Middle East hands such as Lawrence maintained that aerial control was the answer. This was an attractive idea as aircraft were cheap and could cover relatively large distances quickly and administer what was later euphemistically referred to as “Police Bombing.”

The period can be approximately split into two decades. Between 1919 and 1929 the policy promised to deliver everything hoped for, thereby saving the R.A.F. from dismemberment. In fact, the first action by a single aeroplane against a ground army occurred in Sudan in 1916 when a certain 18-year-old John Slessor of later fame bombed and dispersed a whole terrified Moslem army all by himself before British forces even reached the battlefield. This action was lost in the general uproar of WW1 but was the precursor of what was to come.

Unfortunately, similar successes in the first decade of colonial warfare after WWI generated an attitude in the R.A.F. that aerial bombardment and intimidation was the panacea and Army and Navy involvement was unnecessary. This led to mutual hostility and lack of cooperation.

Later the story was different. The tribesmen largely lost their fear of aircraft and succeeded in shooting some of them down. They built air raid shelters and protected cave entrances with blast walls. They also had an effective early warning system of lookouts. Oddly, surviving downed aircrew were usually well-treated and returned to friendly lines in return for money.

The British public and others including many politicians were unhappy with the large casualty toll among innocent people. The destruction of crops and homes meant ongoing hardship for tribal communities. Efforts were made to reduce this impact by dropping warning leaflets and singling out target buildings. Bombing accuracy was poor however and it must be accepted that the “Police bombing” policy was brutal. The life of the squadrons involved is comprehensively covered in the book. Generally, conditions were harsh and the infrastructure underfunded. The terrain, poor aircraft performance and treacherous weather made operations dangerous. A notable operation was the evacuation by air of more than 500 civilians of many nations from a surrounded Kabul during the winter of 1928-29. Afghanistan was in the grip of a civil war and this was the first such evacuation by air, carried out in harsh, cold and dangerous conditions.

The cavalier and superior attitude of the British during these times makes uncomfortable reading nowadays but was common then. Of interest are the number of familiar names that made their debut during WWI and this period – Slessor, Portal, Harris, Salmond, Embry and Dowding to mention but a few.

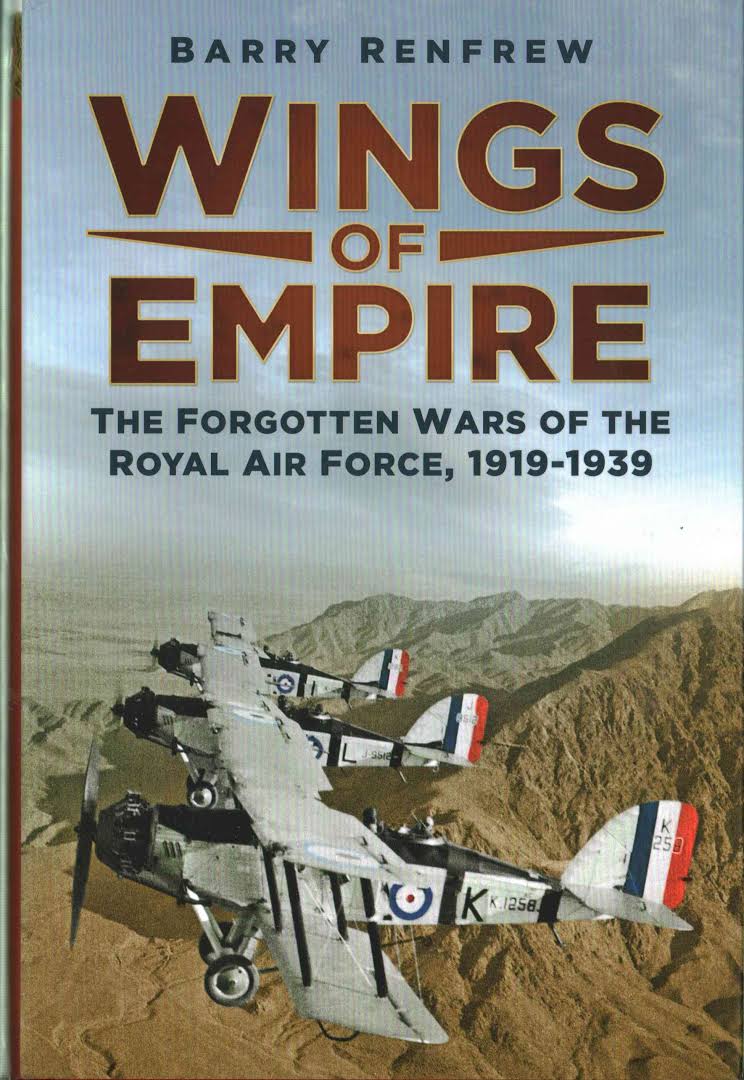

As Mr Renfrew makes clear, aerial policing and bombing delivered a great deal and saved many lives and much treasure on the British side. But, as was proved again in WWII and later, could never provide the compete answer. There are 49 excellent black and white photographs that pull no punches supporting a comprehensive history of the period.

Reviewed for RUSI by Brian Surtees, November 2016

Hardback 368 pp RRP: $43.55

Contact Royal United Services Institute about this article.