If George Martindale were writing today he would possibly be described as ‘a wordsmith’! The further one reads through his letters, the realization that the back page is getting closer far too quickly, and it is the reader’s loss that so many of his letters have been lost forever. With almost invisibility Nicolas Dean Brodie’s commentary provides material on George’s life before his enlistment in the 5th Battalion AIF in August 1914, as well briefly describing each phase of training and theatre of war to put George’s letters to his family members in context. As a 29-year-old working in Melbourne, he was not in the 8th Battalion with his hometown Dimboola peers.

George’s compassion for his mates was evident when he disobeyed orders to go into no-mans-land at night to assist the overworked stretcher bearers bring the wounded back behind the front line for treatment. When he learnt of the death of soldiers from Dimboola or local people at home he asked his family to pass on his sympathy and/or he wrote to them personally.

George landed on Gallipoli on 25th April 1915, and wrote to his mother often written over some period of time. He wrote of Gallipoli to his father after the December evacuation while the AIF retrained in Egypt prior to going to the Western Front. An avid writer, he was rather peeved to have a new writing pad (costing 1s 3d – almost 25% of a day’s pay) pinched from his kit. Wounded at Fromelles in 1916, he continued to write whist being evacuated! Returning to the Western Front as a sergeant at Bullecourt, George was severely wounded in the head, losing his right eye and suffering brain damage in June 1917. After hospitalization in England, he was discharged from the AIF as ‘permanently unfit all services’ and arrived back in Australia in January 1918. He did not work again, and passed away from complication arising from his injuries in 1922.

The beauty of George’s letters lies in the idiom of the day that he used and they contained continual comment or questions about the day-to-day events at home involving personalities both young and old outside his family, as well as the welfare of local farmers and businesses. Fed on a constant stream of local and national papers, George pulled no punches in criticizing the factual inaccuracies that appeared in the press of events he experienced − describing CEW Bean’s The Anzac Book (London, 1916) as ‘a pitiful & puerile production’.

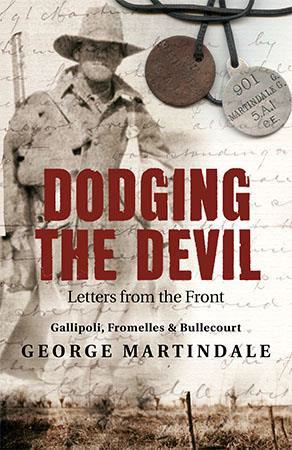

Dodging the Devil is a wonderful collection of the writings of a man larger than life. His wit, idiomatic speech and constant references to people have been made easy to follow in two appendices – Explanatory Notes and Family and Friends (the latter being a miniature Who’s Who) There is no index, but sketches, facsimiles of parts of letters as well as coloured and black and white photographs round out this exceeding readable and unique volume on the First World War.

Reviewed for RUSIV by Neville Taylor, August 2016

Paperback RRP: $29.99

Contact Royal United Services Institute about this article.