Tread softly through the night of gloom,

Away with worldliness and mirth,

“Tis meet to “weep with those that weep,”

A noble son has fall’n to earth,

A son of tender love and care,

Of spirit great and talents rare.

He needed no recruiter’s voice,

His Empire’s need he clearly saw,

And leaving all his heart held dear,

He bravely faced his country’s foe.

For her he nobly fought, and won

A “token” of his King’s “Well done!”

“Good-night,” beloved, sunny, smiling face,

The school-boys’ hero for long years to come,

Long will the record of his fight in space

Live in their memory – “Lyle, well done.”

Kindest of brothers, loving hearted-son,

Rest from thy labours, “Dear Lyle, well done!

We bid thee not “farewell” – “Adieu!”

Thy loved ones did at God’s behest

Offer their sacrifice “to Him,”

Braved the fierce storm, and stood the test.

Lived “unto Him,” each loyal life

Dwells in God’s heart above the strife.

This poem entitled, A Humble Tribute To the Memory of Walter Horace Carlyle Buntine, was published in the June 1917 edition of the Caulfield Grammar School magazine, just a few short days after Royal Flying Corps pilot Lt Lyle Buntine, MC, tragically died in an aeroplane crash in Scotland. This was no ordinary Caulfield Grammarian, for Lyle was the eldest son of the school’s owner and Principal, Walter Murray Buntine.

Lyle’s story is a forgotten one, perhaps because he was not an Anzac, nor a member of the AIF, nor indeed the Australian Flying Corps, although over 100 of his fellow countrymen also died whilst serving with the RFC or RNAS. It should be noted that after his death his family kept as many of his possessions, artefacts, memorabilia and correspondence as possible and these have all been well preserved and curated even until the present day. Dr Michael Molkentin, who has addressed one of our World War 1 Air Force conferences and who recently published an updated history of the Australian Flying Corps, believes that the Buntine Collection of nearly 200 letters is one of the largest written by an Australian pilot, perhaps of any Australian serviceman still in existence in the world today. The Buntine family donated them and the associated artefacts to the Caulfield Grammar School Archives instead of the AWM, because they felt that it was as if Lyle was coming back home to his old school. This precious material is housed at CGS in a state of the art archive facility with safeguards for temperature control and fire hazards in place and a fulltime, qualified and experienced archivist to oversee the entire school’s holdings.

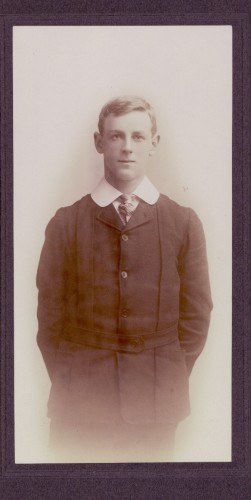

Walter Horace Carlyle Buntine (Lyle) who was born in Toorak on 10th August 1895 and was the eldest son of Walter Murray Buntine, a school master who had just purchased Caulfield Grammar School and was to be its Owner/Principal until 1932.

Lyle was aged 7 when he was enrolled at CGS and proved himself to be an all-round student gaining prizes in most academic subjects, but it was in sport that he excelled. He was a member of Premiership swimming, football and athletics team in 1911 – 13. Outside of school he was placed second in the state championships for pole vault in the competitions held at the MCG in 1913. Along with others he also became a member of the Cadet Unit eventually becoming a Cadet Under Officer.

He left CGS at the end of 1913 and was enrolled in first year medicine at the University of Melbourne when war broke out in August 1914. He immediately tried to enlist, but could not gain his parent’s permission to do so until he had at least finished his first year studies. Finally on 15th May 1915 Lyle enlisted in the AIF and was posted to the Australian Army Medical Corps which trained first at Broadmeadows and then Seymour. It is at this point that his extensive correspondence begins and chronicles his adventures for the next, and sadly final, two years of his life.

He sailed from Melbourne as a young Corporal with the AAMC on 17th July 1915 with 12 of his University medical classmates. Ten of this number served in Egypt, but Lyle and one other companion continued on to England. Life on board the ship proved to be an eye-opener for a young man from East St Kilda and he described 400 drunk AIF soldiers at Fremantle trying to get back on board the ship; a fancy dress ball for the officers and nurses, his experience of a burial at sea, and the absurdity of all NCO’s and officers being ordered to grow moustaches! When the ship reached England safely, Lyle did what just about every Australian in the ‘Motherland” did, he became a tourist and went travelling as often as he could. He had some family connections in England and Scotland and as we shall see they became an important part of his life while he was posted overseas. But only a few days after his arrival he made his way to the airfield at Hendon outside London for a life changing experience.

We may never know why Lyle was so interested in flying. Perhaps it was a result of the flying displays by the famous Australian aviator Harry Hawker at Caulfield racecourse in February 1914. These displays drew crowds in excess of 40,000, so many people that the Victorian Railways had to add extra trains to cope with the numbers. But Lyle described his first flight at Hendon in this way. “On Saturday afternoon what do you think I did? Won’t the boys wish they had been there too? I went out to Hendon and went up in an aeroplane. It is a grand sensation. You get into a little seat behind the driver, the engine starts and away you go over the paddock until finally looking down you see the earth isn’t quite where you thought it was, but quite an appreciable distance away. There is no jar of any kind when you leave the ground. We went for quite a long way and when we got back had just started to volplane down, when another aeroplane crossed our bows and we got backwash from it. The plane stood right on its head and did a dive for about a hundred feet and then came back beautifully on to an even keel. It was great being up in the air and feeling that that you have at last thrown off the fetters that hold you down on earth and soared away up among the clouds.” If not already hooked on flying Lyle certainly was now and a few weeks later wrote to his father to tell him that he was going to transfer to the British Army with the aim of being accepted for the Royal Flying Corps.

Eventually in late September 1916 he was discharged from the AIF and assigned to the 4th Battalion of the Notts and Derby regiment, the Sherwood Foresters, then stationed at Tynmouth. His letters tell of travelling around nearby parts of the countryside by bicycle and train, catching up with some distant friends, acquaintances and family, especially his two younger South African cousins, Jessie and Minnie Buntine, the children of his father’s brother, Dr Robert Buntine a South African MP. They were at girl’s boarding school at Tunbridge Wells. He holidayed with them and other family members at a little fishing village in Scotland from time to time. He also met his younger cousin Jack Gibbs who was serving with the 1st AIF and after serving at Gallipoli was convalescing in London.

Lyle began his army training in earnest trying to cram six months training into five weeks. He writes of endless drill, musketry training, route marches, digging trenches and undergoing night attack exercises. Given his family and church background he was astonished at the bayonet fighting drills where “… they were taught to stamp on an opponent’s instep and kick him and then do quite a lot of other un-British things to him.” He began the process of applying for a transfer to the RFC and training continued in its usual hard slog format enlivened by the occasional mishap, such as occurred during a live examination of a bomb, when the fuse was accidentally lit and a mass exodus ensued with some men jumping out of the third floor windows to hang on to the window sills for dear life. Lyle made excellent progress and was studying for the qualifying test to become a Captain. He had completed all the exams except one, when he received his orders to immediately report to the RFC training depot. His protests were to no avail and he subsequently missed the final exam for a Captaincy by one day!

Lyle was posted to an Oxford University Hall at Reading to begin his theoretical training as an RFC cadet and was surprised to find that no badges of rank were worn. Days began at 6.00am and ended at 4.00pm when cadets were left to their own devices. Studying for the relentless exams took up most of this time as cadets knew that failure meant a return to their Army regiments and a more than likely posting to the horror of the trenches of the Western Front. Lyle reported that most cadets worked until nearly midnight with little time for socializing. Practical courses were held in wireless telegraphy and each cadet was also expected to be able to successfully dismantle and re-assemble aero engines. Lyle noted the great difference between the instructors and calibre of men he had previously served with in his military life. “It will give you some idea of the class of men in the RFC when I tell you that nearly all of them have seen active service and about a dozen of them have the Military Cross or DSO. They are a grand lot of chaps and it’s great being in this Corps. Most of the fellows are very wealthy and sons of, or connections of peers and best of all they are gentlemen.”

When his five week training course was over he was posted to a Flying Squadron at Thetford in East Anglia. His days here were greatly dictated by the weather and the flimsy nature of some of the aeroplanes. Because there was no flying between 9.00am – 5.00pm each day due to strong wind conditions, all flying commenced at 5.00am, ceased at 9.00am then resumed at 4.30pm as darkness fell. The rest of the day was spent in lectures and practical work.

Just a few days after his arrival at the squadron he took his first flight with an instructor and enjoyed it immensely. In Lyle’s case the most common type of aircraft used for this purpose was the Maurice Farman S.11 or “Shorthorn.” This 1912 version was built by the Farman brothers in France and equipped with a 70hp Renault engine which could fly at nearly 70mph, was made with wooden struts, wire bracing and fabric covering. The instructor sat behind the pupil in the nacelle mounted on the lower wing. The Shorthorn was not a good choice for primary training as it was underpowered and had a very high drag factor, being a pusher with a high profusion of bracing wires. Some pilots said that the Shorthorn looked like a Victorian bathtub caught in a baling wire explosion. The Shorthorn at least had the virtue of dual controls, but verbal instruction in the air was impossible. Sometimes notes were passed, sometimes the instructor would kick the seat of the trainee and occasionally a trainee who had “frozen” at the controls would be hit repeatedly to induce the correct action. The pupil sat in front of the instructor and learned to fly by resting their hands gently on the joystick and feet lightly on the rudder while the instructor took it through its paces. In this way they could feel the impulses of the instructor’s movement as he guided the machine through the sky. The shortcomings of the Shorthorn also meant that flights were unlikely if the wind speed was over 5mph!

Lyle wrote that most of the instructors seem to have been good men, but it must be remembered that many of them had already endured the rigours of war and for one reason or another were no longer capable of serving as front line pilots. The RFC command thought that a spell as an instructor would be just the tonic to restore them to good health! These pilots having survived six months or so at the front did not want to be killed at the hands of an inexperienced pupil and so adopted an approach whereby they rarely relaxed their grip on the dual controls and encouraged their charges to solo as soon as possible. The student therefore had to master the use of the rudder pedal as soon as possible during their first few moments of solo flight.

Finally on 7th May 1916, Lyle’s great day arrived and all his diligence and patience during his training came to fruition. “I was informed by my instructor that in about another 10 – 15 minutes I will be able to take up a machine myself. What price me a giddy bird!” Most cadets had only received a few hours dual instruction before they soloed with the first flight usually fulfilling the criteria of 15 – 20 minutes duration, low altitude and within sight of the airfield.

Accidents were a common occurrence with upwards of two dozen crashes a day at most training airfields when training was in full swing and the RFC averaging one death per day amongst student pilots training in the UK. These training airfields would be littered with the remains of crashed machines and ambulances would often keep their engines running constantly in anticipation of the next crash. Once a student pilot had completed this elementary training he usually transferred to an Active Service Squadron for Higher Training, learning to fly on a variety of machines and undertake cross-country flights.

Lyle was also sent to the RFC Machine Gun School at Hythe for further training in aerial gunnery. But his training and travels were suddenly curtailed, when with just 20 hours’ notice in late June 1916, he was ordered on Active Service and to report to RFC 11 Squadron then based at Savy in northern France. He was to arrive on the second day of the Battle of the Somme.

11 Squadron was the first squadron of the RFC to be specifically equipped as a scout unit especially when it was given the Vickers FB5 Gunbus to fly as its major weapon. The squadron flew as part of the Third Wing in support of the Third Army at the Somme and by October 1916 was the RFC’s top scoring squadron. Amongst its notable pilots was Captain Albert Ball VC, DSO and 2 Bars, MC, who was a member of the squadron at the same time as Lyle.

Lyle wrote to his father that his life at the Front was one of hours of idleness punctuated by moments of intense fright. It was here that Lyle’s letters reflect the sort of irony and black humour that seemed to epitomize many servicemen’s reflections on the state of the war in which they found themselves. He described patrols where Archie was popping off all around him and seeing clouds of yellow poison gas, a mine blowing up and encounters with enemy balloons.

Flying a BE8 he engaged enemy aviators at least 15 times with one encounter against the famous German ace Capt. Boelcke who had just had shot down his thirteenth British plane. But Lyle also remembered sanguinely that the most dangerous time for a pilot was when they were learning to fly. His letters sometimes casually mention that he was shot or forced down by anti-aircraft fire six times. He wrote “It’s the usual thing to go up and see the air full of puffs of smoke bursting shells all around you. Some of them come jolly close too. A couple of days ago I came down with the plane riddled with holes; but fortunately I wasn’t hurt.” Or “It makes you think a lot when a shell bursts about 10 feet away and pieces go through the machine as some did this afternoon. But I always remember that you are praying for me and it gives me courage.” Or “This morning I was laying target for Archie. He got a couple of inners, but no bullseyes; but I got back all right.” But often his good fortune held out, “Well I had another fair scrap today and the Hun did some pretty good shooting. One bullet hit my petrol tank so put me rather out of it. Only another half inch and I would have had some sick leave.”

But eventually his luck did run out. On September 9th 1916 whilst acting as a guard to protect some bombers over the town of Bapaume he encountered three German planes and shot one of them down. Having descended too far he found himself the target of heavy ground fire and managed to regain his height, but was then attacked by three other German planes. Lyle in a letter written left-handed from his hospital bed described the end of the encounter in this way. “Then there came a whistle of bullets from behind and I felt as if somebody had hit my right arm with a hammer and it fell to my side useless. We went for each other, but before the Hun went he fired several shots at us which cut all the control wires. The engine was also hit and stopped. Somehow or other I managed to cross the lines and land safely. Then I sent a man for a doctor and lay down on the ground as my arm was pretty painful and I was feeling faint.”

Convalescing in a hospital in England he received a telegram from his Commanding Officer which read, “King has awarded you Military Cross. General sends congratulations. Accept mine.” Lyle wrote to his father, “When I got it I was too overcome for words. I think there must be a mistake for I’ve certainly done nothing to deserve it. I’m waiting now to see if it is confirmed.” Not only was the award confirmed but it was presented to him at a ceremony before he was sent home to Australia on special leave to recover from his wounds, not all of them related to his physical injuries, as we shall see.

His return to Australia was notable for two reasons. One was his arrival in Perth where he was interviewed by a local newspaper; an article which was later reproduced in many Australian newspapers. This was principally because he was one of the very few Australian airmen who returned home during the war and as he was a decorated veteran of the Western Front was able to give a first-hand account of the war. The second was his appearance at a school assembly at Caulfield Grammar where the school magazine reported that Lieut. Buntine received a tumultuous welcome, and on his entrance into assembly, where he had been a schoolboy just three years earlier, the School Captain, voiced the congratulations of the school to the first Old Boy aviator to return with a military distinction. Lt Buntine’s reply took the form of an interesting talk about flying in general and the construction of aeroplanes. The Editor wrote that as the boys looked at the little purple and white ribbon, emblem of the Military Cross won by the speaker, they felt that only the speaker’s modesty prevented them from hearing some stirring tales. Though the boys would gladly have remained all the afternoon listening to similar stories, they greeted with enthusiastic applause the announcement that there would be no more school that afternoon.’

Lyle recovered from his physical wounds and took time to enjoy Christmas with his family and friends and after undertaking a Medical Board at Victoria Barracks returned to duty in England in early March 1917. He took time to explore Ceylon (Sri Lanka) on his way home and as a decorated and wounded airman was feted by the ship’s passengers. Lyle left the ship at Marseille and travelled by train to England, a fortunate occurrence as the ship was torpedoed and sunk on its way into the English Channel.

It was on 25th April 1917 that Lyle, along with several other Australian officers, men and nurses were invited to tour Windsor Castle and while they were there King George V heard of their presence and asked to meet them. Lyle wrote “The men and the nurses simply marched past, but the King stopped us and shook hands with each officer in turn. As soon as he saw that I had the MC he singled me out and spoke to me for about 10 minutes. He asked me if I had received the MC from himself and when I said no, he replied, Well you must come on Wednesday and I will present it myself.” Lyle continued, “I was so excited I didn’t know whether I was standing on my head or my heels. I have a happy sort of recollection of saluting about five times and standing as stiff as a poker while being spoken to by the King and then the Queen. But of what I did and said I have no idea. When I got outside I found I was as red as a lobster with beads of perspiration on my forehead and I was trembling all over with excitement. PS. I haven’t washed my hands yet and may not have by the time you get this letter.” So on 4th May Lyle went to Buckingham Palace and was duly presented with his MC by the King.

On June 3rd 1917 Lyle wrote to his mother, “I had a Medical Board some time ago and have been waiting to be posted to a squadron or to some work, however the Medical Board marked me permanently unfit as a pilot or observer and recommended that I should be allowed to return to Australia to finish my Medical Course. This recommendation is being considered by the War Office and meanwhile I have been appointed to a job on the staff as an Instructor in Aerial Gunnery at Turnberry on the east coast of Scotland.” And so it was that Lyle then related taking a plane and flying out to sea and doing loop-the-loops and Immelman turns and spirals just to see if he could stand it. Thinking that the Medical Board was wrong, he finally admitted in a letter to his younger brother that “I’m afraid I’m not much good now and it took a terrible effort of will not to jump out of the bus. When I came down I had a splitting headache and generally felt giddy and knocked up.” On 15th June Lyle wrote to his father expressing his frustration at the delay in receiving his discharge and tragically it was while the creaky wheels of bureaucracy at the War Office decided whether to send him back to complete his medical degree in Melbourne, that he met his death.

On June 20th 1917 Lyle’s father received a telegram at CGS informing him that Lyle had been killed the day before in a flying accident at Turnberry. A Court of Inquiry later found that whilst Lyle was acting as an observer on a camera practice flight, the experienced pilot inexplicably stalled the plane and they crashed in a nose dive with the plane bursting into flames on impact. Lyle’s CO wrote sympathetically to WM Buntine and whilst writing of his regret at Lyle’s death, pointed out that the Medical Board had told him not to fly, that he was well aware of this fact and he had received this advice in writing. Why Lyle chose to ignore this directive is not known as he had stated to many people that he would definitely not be flying again. It would not be until early September that his discharge papers finally arrived from the War Office and were forwarded to his grieving family.

Many bereaved Great War families in Australia tried to preserve the memory of their lost loved one through the keeping of artifacts, letters and photographs, in some cases as a shrine in the family home. Author and researcher Maree Luckins suggested, ‘Wartime loss was responded to with a series of personal and social acts. This included writing letters, making scrapbooks, wearing mourning black and being part of a crowd of these mourners. It also involved focusing on an object and investing it with the memory of an absent body. She further observed that, ‘Small items, such as wallets, photographs, coins, postcards, letters and diaries were in many instances, the only material things left for relatives, and they became important in the process of accepting loss and memory-making. She further noted, ‘Personal effects were considered substitutes for the absent body and thus became treasured, even sacred objects of memory, kept in a ‘Drawer of Remembrance’ or placed on display on a mantelpiece, drawer or bedside table inside the home.

Following Lyle’s death the Buntine family followed this practice through the keeping of a large collection of Lyle’s letters, memorabilia and associated artifacts and thus the role of material culture in the commemorative process managed to preserve his memory. A special wooden glass-fronted display case was constructed which held many precious objects associated with his war service such as his medals, ‘flying wings,’ rank insignia and his “Dead Man’s Penny” and this treasured icon was wall mounted and displayed in the family home. His flying helmet and even the propeller tip from his downed plane was kept as well as the very German machine gun bullet that had wounded him! At CGS the process went one step further with Lyle’s father, WM Buntine, the Principal even naming a House at the school in his memory.

And so to conclude the tragic story of the Buntine family in the Great War. Walter Murray Buntine, the Principal of CGS was a family man with a devout Christian faith, but this deep seated belief must have been sorely tested as a result of the tragedies that befell his own Buntine family and that of his wife’s relatives, the Gibbs family as a direct result of the Great War. His oldest nephew Richard Horace Maconochie (Mac) GIBBS (1908 – 11) was awarded a posthumous MC after being killed at the Battle of Fromelles. Walter Horace Carlyle (Lyle) BUNTINE (1903 – 13) We have already read Lyle’s story. John HARBINGER GIBBS; (1912 – 1914) was invalided home from Gallipoli for treatment for tuberculosis, under his doctor father’s care, but died on 13th October, just a month after his arrival in Australia. Dr Robert Andrew BUNTINE, and his eldest daughter Jessie were drowned in September 1918 when their ship was torpedoed by a German submarine. Dr Richard Horace GIBBS father of Mac and John became the senior surgeon at Macleod Military Hospital in Melbourne, but died at the intersection of St Kilda and Domain Roads when he fell from the rear platform of a cable tramcar to the roadway. Walter Murray BUNTINE had lost six family members in a three year period between mid-1916 and mid-1919.

The story of Lyle Buntine and his extended family is one that has rarely been told and although it does not tell of the wider sweep of battles and the tactics of generals and armies, it serves to remind us that each of the names on our war memorials represents a life, a young life that once had hopes and dreams the same as ourselves. It is salutary to think of the work, joy and contributions that each of these people would have made to Australia and humanity had they lived. But perhaps in the end, some of the words of Lyle’s Poem of Tribute try to make some sense of his tragic loss.

“Good-night,” beloved, sunny, smiling face,

The school-boys’ hero for long years to come,

Long will the record of his fight in space

Live in their memory – “Lyle, well done.”

Kindest of brothers, loving hearted-son,

Rest from thy labours, “Dear Lyle, well done!”

Contact Daryl Moran about this article.