It seems very strange that in Australia we have – neglected, forlorn, and abandoned – one of the foremost examples of military technology in the world, but it is not in a museum.

This cutting edge vessel is lying half-submerged off a beach near Melbourne. It should be inside being conserved. But for years there has been little but argument about the wreck of the warship Cerberus.

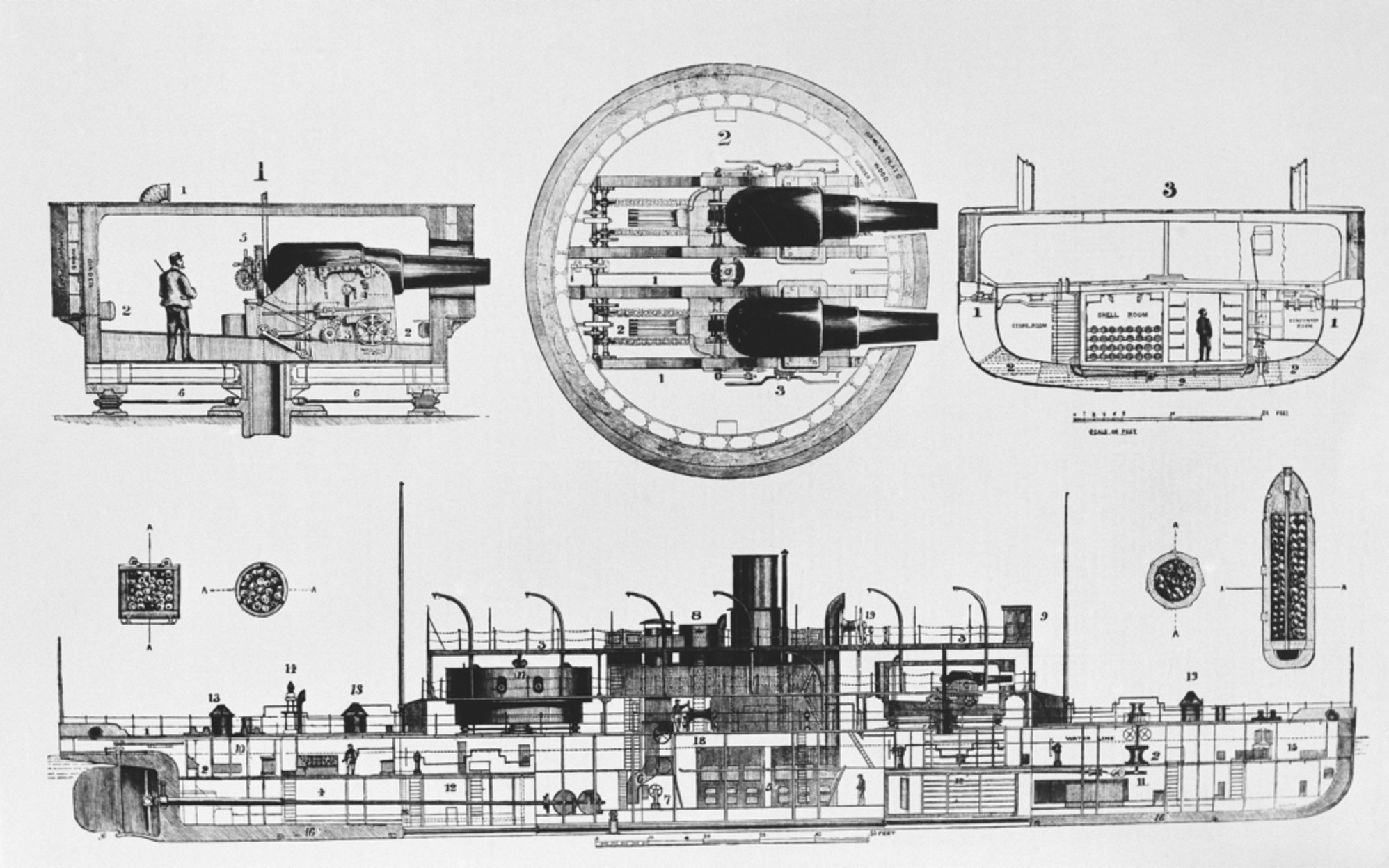

What makes this shipwreck unique? Three things. This rather curious ship is one of the world’s last monitors; the only surviving vessel of the Australian colonial navies, and one of only three surviving ships on the planet with Coles turrets. Cerberus was also the first British warship powered purely by steam; the first warship with a central superstructure, and the first with gun turrets mounted on its central superstructure.

To explain; first, Cerberus is one of nine examples of a monitor – a special type of warship – left in the world. In the mid-1800s wind-powered navies were fast disappearing, to be replaced by ships with engines, with armour protecting their guns, engines and crews. The first major engagement between these new “ironclads” was fought between the Monitor and the Virginia in 1862 during the American Civil War. From then on, engines and armour would be a considered characteristic for all new warships.

Monitors only had a brief lifespan in around 50 years of wildly competing warships designs. Their concept was to be a floating gun platform used in harbours and near coasts rather than a seagoing ship. Their hulls were broad and rather flat, and they risked being swamped. Finally navies settled on the dreadnought design, with a streamlined metal hull and a combination of armour, guns, and speed which made the monitor obsolete. After serving as a floating artillery base deterrent in Port Phillip Bay until 1926, Cerberus was scuttled as a breakwater in her present location in Half Moon Bay.

The second special characteristic of Cerberus is its main weapon, its Coles gun turrets. These are named after their inventor, Captain Cowper Phipps Coles of the Royal Navy. Each of the Australian ship’s has two guns. While most original ironclads had their weapons projecting through ports in the sides or in turrets with the guns able to be traversed – moved sideways – only a little, the Coles turret revolved. This was the forerunner of the turrets you see today even on the most advanced warships, usually alongside missiles. The naval gun still survives and delivering artillery fire from the sea is still most useful. For example, RAN destroyers carried out many fire missions in the Vietnam War, and in 2003 HMAS ANZAC delivered scores of rounds from its 127mm gun in the Iraq War, completing seven fire missions over a period of three days.

There are now only two other ships with a Coles turret known. Schorpioen, a monitor built in France for the Royal Netherlands Navy in the 1860s, survives as a museum vessel in the Dutch Navy Museum. The Peruvian turret ship Huascar in Chile also has a Coles turret. For Australia to let the only other piece of this technology in the world fall apart before our own eyes is nothing but neglect.

Third, Cerberus is a last survivor of a very strange period in Australia’s history, one where we had small individual navies for several of the colonies which eventually became states. Yes, Queensland had its own navy; so too did South Australia, and Victoria. NSW was the home of the Royal Navy’s squadron, so had a permanent presence of warships.

Why did the colonies have their own navies? Australia, 150 or so years ago, was a very different place to today. The tiny colonial settlements had much to be wary of. Invasion by another country was a real enough possibility: Japan, Russia, even the United States were feared. And a naval warship appearing off Melbourne, for example, was a terrible weapon. It could heave to off your port and open fire with its guns, shelling your buildings and people with little fear of retaliation. What could you do even with a small army? Nothing except open fire with what artillery pieces you possessed, in which case the ship would merely sail away to another location and open fire there. So many colonies purchased warships to deter enemies.

Cerberus, even as a wreck, is the last such substantial example of a colonial warship. There is the hull of Protector, from South Australia, sunk as a breakwater off Heron Island on the Great Barrier Reef, but only a section remains, whereas Cerberus’s site contains four 10-inch guns; two turrets, a steering tower, and much of the hull and decks. There is enough left to make a substantial and significant exhibit.

Over the years since the obsolete warship was sunk there have been many efforts to rescue what is left, often led by the Friends of the Cerberus Inc. In 1993 the wreck collapsed somewhat, and subsequently the guns were taken out of the turrets and deposited on the seabed, with a protective coat added. This was both to remove weight from the turrets and to conserve them: being fully immersed in seawater is better for rust control than being constantly wet and then dry. A suggestion was made to stop the wreck settling further every year by filling it with concrete, but this has now been replaced by a suggestion to pump polyurethane under the turrets.

The wreck is technically owned by the City of Bayside Council, but asking a Council to engage in what is really needed – to remove the wreck and place it in tanks to leach the salt away – would be well beyond them. The state of Victoria needs to come to the task and not only remove and conserve the wreck, but come up with a display centre and staff. This has been done successfully in many places around the world, and results in a tourist attraction being created. The Mary Rose in the UK, the Batavia in WA, and the Vasa in Sweden are examples. The USA’s Monitor, perhaps the most famous of this ship type, was recently recovered and is being prepared in this manner.

If Victoria does not want to do this, then the federal government should. In that case, lifting the Cerberus, placing it in Canberra’s National Museum, and securing a vital asset not only for Australia but for the world should be done as soon as possible.

Written by Dr Tom Lewis OAM.

Contact MHHV Friend about this article.