In early December 1915, 85,000 men, 5000 animals, 200 guns, and multiple stores and ammunition crowded Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay in Gallipoli to start the phased evacuation, and by nightfall on December 19, only 1500 Anzacs remained.

At 1.30am the following morning the final phase of the evacuation began when “down dozens of little gullies leading back from the frontlines came little groups of six to a dozen men”.

Before sunrise, the evacuation from Anzac Cove and Sulva Bay ended. The campaign left 10,500 Anzacs dead.

The well-planned and executed evacuation, later characterised by Monash “as the greatest joke – and the greatest feat of arms in the whole range of military history”, became part of the Anzac legend.

After the failure of the August offensives to break out of Anzac Cove, the Allied leadership realised the campaign was untenable and an evacuation was required, an action in which up to half the Allied force might be lost.

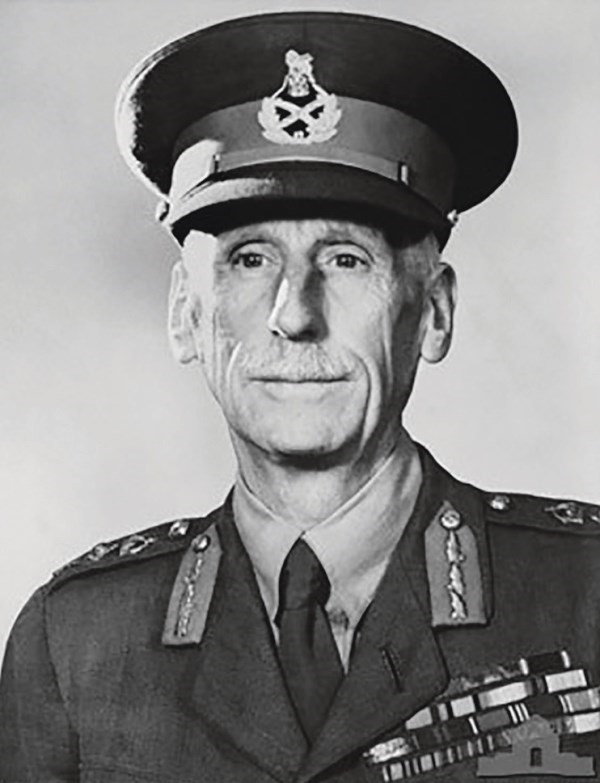

In October, then Brig-Gen Cyril Brudenell White, Chief of Staff of the Anzac Corps, began planning the evacuation.

Born in Victoria, a professional soldier in the emerging Australian Military Forces (AMF), Brig-Gen Brudenell White was a rising star. He was the first AMF officer to attend British Staff College in 1906, and was recognised for his meticulous planning abilities based on comprehensive understanding of conditions, ground and troops involved.

Central in planning the landings – he was now central in planning the evacuation.

Brig-Gen Brudenell White faced two simple choices: conduct a fighting withdrawal that would end with the pursuing Ottoman’s firing down onto the withdrawing forces, or a silent withdrawal using deception, accepting the risk that a small rear guard might be overwhelmed if the deception was discovered.

He chose the second option. Like all good plans, his was simple – gradually withdraw the men, animals and equipment while convincing the Ottomans that the Anzacs were simply preparing for a defensive winter campaign.

The first two stages of evacuation (the drawdown of troops, animals, guns and stores to a point where they could still hold off a major attack for about a week, the planning guidance being: “two rifles per yard and one third of the present artillery”) were kept secret from all but those who needed to know, including the troops.

From late November, deception efforts included nearly all firing from the Anzac positions being stopped, to condition the Ottoman troops to interpret inactivity as routine.

Campfires remained burning and animals and equipment were withdrawn at night, with some being returned during the day to give the appearance of normal operations.

In the final stage, the remaining 20,000 troops left under the cover of darkness on December 18 and 19.

They moved out in a coordinated withdrawal, the last being those on the frontline itself; following trails of oats and prepositioned white-washed sandbags left to navigate to embarkation points.

Gullies and saps were prepared with barbed wire and mines. Boots and bayonets were wrapped with sandbags to dim noise and shine. Drip rifles provided sporadic firing to imply the trenches remained occupied long after the last Anzac had left.

After evacuating, the Anzac Corps re-formed in Egypt with forces deploying to the Western Front and Middle East campaigns.

Brig-Gen Brudenell White remained as Chief of General Staff of 1 Anzac Corps; subsequently moving on to assume responsibility as Chief of General Staff for the British 5th Army.

Achieving the position of Chief of the General Staff for the AMF, he was killed in Australia in August 1939 along with three government ministers – in an aircraft crash, which deprived Australia of four of its most experienced (military) leaders, just before WWII.

Major Ian Barnes

Contact MHHV Friend about this article.