Days before and after the launch of Operation Overlord on 6 June 1944, D-Day, around 13,100 American paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions and some 7,900 British counterparts of the 6th Airborne Division were dropped behind enemy lines.

They played a crucial role in securing the flanks of amphibious landings on the Normandy beaches. But these parachute drops almost didn’t happen. Airborne operations were in bad odour after their abject failure in Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa of November 1942, and Operation Husky, the Sicily landings in July 1943. When it came to planning Operation Overlord, General Eisenhower had serious doubts about an airborne component, shared by some of his senior staff. He formed a board to review the airborne concept. As Phillip Bradley explains, Eisenhower’s fears were ultimately dispelled by the spectacular success the US 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment’s drop at Nadzab during Operation Postern, the combined US-Australian amphibious and airborne operations in September 1943 to take Japanese occupied Lae on the north-eastern coast of New Guinea.

Bradley’s finely detailed account of Operation Postern is also broad-ranging, encompassing the whole strategic and tactical environment shaping the main assault. It will no doubt remain the most authoritative source on the campaign for many years to come. Opening chapters cover Australian observation posts and parties skirting the Japanese zone of occupation along the Markham River valley north-west of the port of Lae. Made up of troops from the New Guinea Volunteer Rifle (NGVR) militia and independent (commando) companies of the Australian Army, they gathered vital intelligence while evading intense enemy ground and air patrols. Captured members of these observation parties faced summary execution. Defying the constant threat of detection and harassment by the Japanese, not to mention hunger, fatigue and disease, their base camps shifted around various points of the valley. In succeeding chapters, Bradley describes corresponding reconnaissance parties patrolling the Saruwaged Range and Huon Peninsula north of Lae, led by Captain Peter Ryan, author of the classic wartime memoir Fear Drive My Feet.

General Macarthur, the Allies’ aggressive new Supreme Commander, expected more than just observation, however. On the night of 29 June 1942 commandos of the 2/5th Independent Company assisted by NGVR raided the Japanese outpost at Heath’s Plantation. While some 21 enemy were killed with the loss of one Australian, the action achieved little more than provoke a Japanese mopping-up operation which drove Australians from the valley for over a year. Further offensive moves would have to await the arrival of US forces north of the Owen Stanley Range, which began slowly in October 1942. But a plan urged by General Thomas Blamey, Allied ground forces commander, to capture Lae and Salamaua (further down the coast) was under discussion. Code-named Haggis, the operation envisaged a landing of troops at the former airfield site at Nadzab in the Markham Valley.

These land-based precursors to Operation Postern were complemented by activities at sea and in the air. The Japanese considered the Lae-Salamaua sector vital in determining the result of the New Guinea Campaign. In March 1943 a convoy made up of eight transports carrying infantry reinforcements, escorted by eight destroyers, left Rabaul headed for Lae. It was attacked by Allied long-range bombers in the Bismarck Sea, resulting in all of the transports being sunk along with four of the destroyers. Of the 8,740 men on the convoy vessels, 2,890 were lost, many of them army and marine troops. Some of the sunk transports were carrying supplies of aviation gasoline, loss of which wrecked the plan to use Lae as a front-line air base. As a consequence of this “disastrous defeat”, the Japanese found it increasingly difficult to supply Lae by sea. They resorted to scouting overland routes across the near-impassible mountain ranges to the north-west or deploying motorized landing craft (MLCs) from their bases in Rabaul and Wewak, further up the northern coast of New Guinea. Hugging the coastal inlets and river mouths, they were hunted remorselessly by American aircraft and PT boats. Between 24 July and 3 August some 94 MLCs were destroyed and another 60 damaged. I-Class submarines were also used for supply purposes, but these were hampered by limited space capacity. They carried no more than 40 men, 20 of whom had to be crammed into the forward torpedo room measuring 3.6 by 2.3 metres and only 1.7 metres high, for three days at a time.

Such constraints imposed a ceiling of 10,000 on the number of men stationed at Lae and Salamaua. And interdiction of Japanese fuel supplies rendered the Lae aerodrome a sitting duck to American A-20 Havoc and B-25 Mitchell bombers escorted by P-38 Lightning fighters. For many reasons, morale amongst the estimated 4,260 field troops and 1,640 other personnel at Lae was estimated to be “very low”.

In the meantime, both sides set about constructing the infrastructure necessary to either defend or attack the occupation zone. On the Japanese side, efforts to build a military road from Bogadjim, much further up the coast, down to the Ramu Valley, touching the upper reaches of the Markham Valley, were blocked by commandos of the Australian 2/2nd and 2/7th independent companies in August 1943. They did complete three new airfields around Wewak beyond the current range of Allied bombers, but the protection of distance would be short lived. As Bradley explains, “whatever clashes took place on the ground, the prerequisite for any Allied operation against Lae would be control of the air over New Guinea”. Allied resources were poured into a project which became a lynchpin of the whole campaign. After considering Salamaua and other options, Allied air commander US General George Kenney settled on an overgrown pre-war supply strip at Marilinan, south of the Markham River, as the advanced air base and refueling point to cover an assault on Lae. The base was actually built at Tsili Tsili, a better site 6 kilometres away. In June 1943 the American 871st Airborne Engineers Battalion was flown in from the US on 30 C-47s and construction was soon underway, protected by the Australian 57/60th Infantry Battalion. Vast quantities of equipment were flown into Tsili Tsili, a volume of industrial output and supply the isolated Japanese had no hope of matching. Peter Ryan observed that “a major operational base had sprung from the earth just at the back door of Lae, the enemy’s main stronghold”.

It took the Japanese two months to notice the activity at Tsili Tsili and their belated air attacks were ultimately defeated by the base’s complement of Thunderbolt and Lightning fighters. General Kenney soon had 64 heavy and 58 medium bombers at his disposal. In early August 1943, B-17 Flying Fortresses and Liberators struck the four Wewak airfields followed by a succession of raids which neutralized Japanese air strength in the region. The bombers had done their job and now a fleet of C-47 troop carrier aircraft was rolling into Tsili Tsili.

During this time the fate of Lae was absorbed into General Macarthur’s grand strategy for the South West Pacific theatre, known as the Cartwheel plan. Essentially it entailed occupation of areas capable of development into forward bases. Planning took place at advanced land headquarters in Brisbane under the Direction of Deputy Chief of the Australian General Staff Major-General Frank Berryman. The stage two objectives of Cartwheel were to seize the Lae-Salamaua-Finschhafen-Madang area, which from May 1943 was given the code name Operation Postern. The plan envisaged an amphibious landing on the coast near Lae and an air-ground operation against Nadzab airfield, 30 kilometres west. The amphibious phase called for transporting an Australian division up the coast from Buna using small landing craft. But most of the naval assets in the Pacific were assigned to US Admiral Chester Nimitz’s Central Pacific Area. Necessity gave rise to ‘McArthur’s navy’ in the form of US Rear Admiral Daniel Barbey’s 7th Amphibious Force, underpinned by his blue-water (oceangoing) amphibious doctrine.

This prescribed the use of smaller ship-to-shore craft in the form of various grades of ‘Higgins Boat’ or landing craft with hinged bows. Barbey’s force took over command of the US Second Engineer Special Brigade (2nd ESB) for upcoming operations, comprised of the 532nd, 542nd and 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment (RBSR). For the assault on Lae, about 65 smaller landing craft, landing craft vehicle personnel (LCVPs) and landing craft tank (LCTs), from the 532nd ESBR were initially placed under Barbey’s command. As a precaution against rough weather conditions, larger and longer ranged landing craft infantry (LCIs) and landing ship tank (LSTs) would be needed as well.

The initial Postern plan called for General George Vasey’s Australian 7th Division to make the amphibious landing, in view of its experience of jungle conditions during the Papuan campaign. However an outbreak of malaria amongst the troops forced a change to Major-General George Wootten’s 9th Division, newly arrived from the Middle East. In Cairns, the men underwent intensive training in jungle warfare and the use of landing craft. The day of their amphibious landing at Lae, tentatively 1 September 1943, was designated D-Day and the operation scheduled for 2 September at Nadzab, deploying 7th Division, was Z-Day. Postern’s over-water operations were under Barbey’s command with vessels supplied by US 7th Amphibious Force. Wootten and the Americans agreed to land 7,000 personnel on D-Day, another 2,400 on D+1 and another 3,600 on D+2. Two beaches was earmarked for the landings, Red Beach 22 kilometres east of Lae and Yellow Beach 5 kilometres further east to protect the flank of the main beachhead. Australian 20th Brigade’s 2/15th Battalion was to land on the right or eastern flank of Red Beach and 2/17th Battalion on the left closest to Lae. The 2/13th Battalion would land on Yellow Beach. In addition the 2/23rd Battalion would be attached to 20th Brigade, and 26th Brigade would follow-up the initial landings and move through the beachheads. The force would assemble at the staging post of Milne Bay where loading of stores, equipment and vehicles was completed by 1 September.

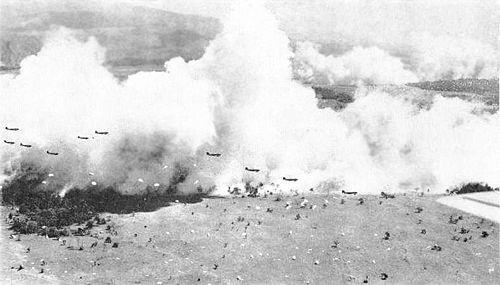

Capture of Nadzab airfield was the second phase of Operation Postern. An earlier plan to carry 7th Division by ship and river craft was abandoned in favour of transport aircraft from Port Moresby. By mid-August General Kenney had 120 such aircraft available with 72 of those in daily use. Kenney’s air arm would play a vital role in Postern, carrying troops, proving fighter escort and laying down out an intense preliminary bombardment of Lae and Salamaua. General Berryman directed that the main role of 7th Division was to prevent the enemy overland reinforcement of Lae and helping 9th Division capture Lae. Vasey requested that a full US paratroop regiment be deployed to take the airfield preliminary to landing his men, and Bradley notes that he forged a ‘splendid and consistent’ relationship with Brigadier-General Ennis Whitehead, one of Kenney’s senior commanders. By 23 August, Colonel Ken Kinsler’s 503rd US Parachute Infantry Regiment made up of three battalions was in Port Moresby and 54th US Troop Carrier Wing was assigned to carry them into action at Nadzab. The two units decided to use a drop formation of six planes echeloned to the rear with a 30-second gap between each formation. Each battalion would have a separate drop zone. Their mission was to secure the airfield and establish a defensive perimeter to prevent adverse enemy movements. Meanwhile 7th Division underwent their own intensive training with C-47 transport aircraft.

From Milne Bay the first echelon of 9th Division Australians stopped off at Buna before proceeding to Lae on the early morning of 3 September 1943. Four American auxiliary personnel destroyers (APDs) carrying 16 LCVPs landed assault companies of the 2/13th Battalion at Yellow Beach and companies of the 2/15th and 2/17th Battalions at Red Beach. The second echelon included elements of 2/13th Battalion landing at Yellow Beach and others from 2/15th and 2/17th Battalions at Red Beach, followed by more 20th Brigade units. The third echelon carried a battalion from the US 523nd EBSR, and another 12 echelons landed by D-Day +13. The waters were smooth throughout, as five destroyers provided a preliminary bombardment. The Australians made the beaches without opposition on the ground but on the morning of 4 September Japanese Oscar fighters strafed the landing craft and three Sonia bombers came in for a run, destroying one LCI.

Some of the LSTs bringing in the 6th echelon were also attacked from the air east of Morobe. LST 471 was hit by a torpedo killing 34 commandos of 2/4th Independent Company. Nevertheless by nightfall all Allied objectives had been achieved; the three assault waves landed 3,780 troops while the follow up echelons brought in another 2,400 along with anti-aircraft batteries, vehicles, ammunition and stores.

Z-Day went more or less according to plan over Nadzab. One war correspondent wrote “it was all over so quickly, that all one was left with was of a vision of parachutes billowing briefly, and then a big concentration on the ground that looked like so many sheep”. Bradley notes that General Kenney was impressed by the near faultless parachute drop, calling it “a magnificent spectacle”. The Japanese had a different view. Lieutenant-General Kane Yoshiara later wrote “while the Lae units were keeping at bay the tiger at the front gate, the wolf had appeared at the back gate”. Engineer and pioneer units cleared the runway and C-47 traffic poured in, some from Tsili Tsili and others acting as a ferry service for 7th Division troops from Port Moresby via Tsili Tsili. On 7 September 66 planeloads landed. Tragically, 62 Australians, mostly from the 2/33rd Battalion, were killed when a loaded American bomber crashed into the trucks conveying them for embarkation in Port Moresby.

On 2 September, 9th Division began to march west from the beachheads established on D-Day towards Lae. Dense vegetation and swampy terrain were bad enough but the Australians also had to cross six flood-prone rivers. At first, advance battalions evaded larger Japanese patrols, but skirmishes became unavoidable and casualties were incurred. On 8 September, 26th Brigade moved up the Burep River and over to the Busu River at a point where the locals had constructed kunda-vine suspension footbridges over the fast and strong current. The 24th Brigade travelled parallel along the coast. As the Brigade’s 2/28th Battalion attempted a crossing of the Busu’s mouth they met heavy resistance. They scouted upstream and looking for a place to wade across and overran the Japanese positions, but some were swept away by the raging current. On 11 September men of 26th Brigade further inland began building a bridge over one stream of the Busu and two days later a span of ‘box-girder’ bridging arrived to cross another stream, and a third section was added on the 14th. The Brigade pushed forward, joined by 24th Brigade moving out if its bridgehead.

Only Japanese stragglers were encountered on the outskirts of Lae, which fell to 9th Division on 16 September. Meanwhile at Nadzab, 7th Division’s 2/25th Battalion had started for Lae on 7 September, attacking the succession of plantations turned Japanese outposts lining the way, Jensen’s, Whittaker’s, Heath’s, Edwards’ and Jacobsen’s. Some of these clashes were fierce, with at least one bayonet charge by the Australians. On 13 September Private Richard Kelliher of the 2/25th earnt a Victoria Cross for silencing a machine-gun post and rescuing wounded mates at Heath’s. A leading 2/25th patrol reached Lae on 16 September, finding it deserted. Proceeding towards the waterfront “they met up with surprised 9th Division troops who had approached in attack formation”.

The Japanese position was hopeless. Lieutenant-General Nakano, commander of the garrison, decided against Gyokusai, final battle to the death, and ordered a retreat over the Surawaged Range to the north coast. Although a company of 7th Division’s 2/16th Battalion was tardily dispatched to cut off the expected withdrawal route at the Bumbu River crossing, the Japanese had gone.

While they were pursued by Australian other patrols around the next major obstacle, the Busu crossing further upstream, the desperate Japanese band made it up into the Saruwaged. The precipitous mountain track took its toll and many succumbed to hunger, dysentery, malaria, diarrhoea or bitter cold. Some even resorted to cannibalism. “The bodies of those who simply could not go on started to pile up on both side of the path”, wrote Private Hiromasu Sato. On 18 October, the survivors finally made it across the range to Kiari. Of the 8,650 who retreated from Lae 33 days earlier, around 6,544 were still alive.

Review by John Muscat for MHSNSW Reconnaissance, Spring 2019

Contact MHHV Friend about this article.