This article is the text of a lecture delivered to the Society’s meeting on 7 December 2019.

Confrontation or Konfrontasi was a rather complex situation since it arose from the murk of Indonesian politics. It ebbed backwards and forwards and was influenced by domestic and foreign politics, economic factors and nationalism. Throughout its duration Confrontation was overshadowed by the spread of communism and the Cold War. This is a simplified overview to give the reflections some context.

The seeds of confrontation between Indonesia and Malaysia can be traced to the very end of the Second World War when Indonesia was created out of the former Dutch Colonies. In 1945 Sukarno became the first president and achieved independence in 1949. After an armed confrontation with the Dutch lasting some 16 years he annexed West New Guinea in 1961, just when the Dutch were about to hand it over to an indigenous government.

In the 1960’s Sukarno had adopted an aggressive foreign policy to secure Indonesian territorial claims. The successful annexation of West New Guinea led Sukarno and his foreign minister, Dr Subandrio, to believe they could succeed in opposing the creation of Malaysia by possibly expanding into North Borneo. They were prepared to use violence, but did not want a full-scale war. The policy of Konfrontasi was formally announced by Dr Subandrio in January 1963 as a result of this thinking.

The first action was in the form of Indonesian military support for a December 1962 coup attempt in Brunei. This was quickly put down by British and Gurkha troops flown in from Singapore, but armed incursions continued throughout 1963. Although resistance to these incursions by British troops in Borneo should have indicated that the policy was failing, Indonesia escalated the conflict in 1964 by attacks on mainland Malaya. Tensions increased and offensive air and sea operations were planned by the British. Instead of forcing the Malaysians and British onto the defensive, a build-up of forces followed which put the Indonesians themselves on the defensive and led to the official end of conflict in August 1966.

In the 1960’s Australia had three battalions of infantry in the regular army. One battalion was based in Malacca, Malaya on a 2-year rotation as part of the Far East Strategic Reserve. A second was held for possible service in the South East Asia Treaty Organization area or in Papua New Guinea, and the third was either reorganising after Malayan service or preparing to go there.

From 1959 to 1963 3rd Battalion Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR) was based in the Brisbane suburb of Enoggera, and was a Pentropic battalion with 5 rifle companies, each with 5 platoons, a support company and an administrative company. It had an overall strength of some 1,200 men – a big battalion. In 1963 it was warned for deployment to Malaya and had to reorganise and downsize to a strength of about 650 to become a tropical battalion of 4 companies, each with 3 platoons, and a reduced sized support and administrative company. It was a deployment of people not equipment, as the battalion took over the transport and equipment of the in situ unit, at that time 2 RAR. In addition to deploying the troops, families also accompanied the battalion to Malaya. This required family inoculation and the packing up of limited domestic items. Furniture, utensils etc were not required as fully furnished houses were provided.

Movement was by chartered Qantas 707 direct to Singapore and then by Malay Airways DC3’s from Singapore to Malacca. The battalion was based at Terendak Cantonment just north of Malacca. It commenced acclimatization and garrison duties. For the first 6 months the battalion trained with other units of the 28th Commonwealth Brigade, which also included a British and a New Zealand battalion. On one brigade exercise, officers from the British battalion, the Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry or KOYLI’s, were assigned as umpires and assessors of 3RAR. The exercise report stated that 3RAR was unlikely to be able to sustain itself on operations as they were too frugal and did not deploy their officers’ mess and silver to the field!

The KOYLI’s had been deployed to North Borneo in 1963 so there was an awareness of the worsening situation in Borneo. Australia had already deployed advisors to South Vietnam in 1962 and there was considerable speculation at this time as to whether additional troops would be sent there. Taking advantage of the fact that 3RAR was already deployed to the Far East, during 1964-65 the government allowed all officers of the battalion to be sent to South Vietnam for a 2-week orientation tour. Australia committed combat troops there in April 1965!

In early 1964 the Malaysian Government requested that the Australian and New Zealand battalions be made available for anti-terrorist operations on the Malay-Thai border to allow the release of Malaysian battalions for operations in Borneo. The Malaysian Emergency had only concluded three years before, and the remnants of the Communist Terrorists known as CT’s had withdrawn into Southern Thailand. In February 1964 3RAR deployed to the Thai border on Operation Magnus and remained there until relieved by 1 Battalion Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment in April.

Platoon patrol bases were established and resupplied by air drop, helicopters, mules, porters and armoured motorized rail cars known as Wickham Trolleys. Although no contacts were made, valuable experience was gained in jungle warfare as the battalion was on a full operational footing.

Both Malaysia and Britain had also asked for Australian troops to be sent to Borneo, but the Australian Government was reluctant to commit combat units. The Australian Minister of External Affairs, Garfield Barwick announced a policy of “carefully graduated response” to the request for support. Australia agreed to supply Malaysia with stores and military equipment and to train Malaysian soldiers in both Australia and Malaysia. In April 1964, a squadron of Australian engineers was sent to Borneo and two Royal Australian Navy (RAN) minesweepers deployed to patrol the coastal area. A total of 12 RAN vessels patrolled Malaysian waters at various stages of the conflict. It should be noted that throughout the whole period of Confrontation, Australia continued to provide foreign aid to Indonesia, and maintained an intake of Indonesian students to Australian Universities. Our military support to Confrontation was broadly supported both by the public and the Labor opposition in parliament. The only critics seemed to be those who pressed the government to do more rather than less.

The battalion conducted trials of the suitability of Nuclear, Biological and Chemical (NBC) suits in a tropical area which required troops to have a small thermometer inserted into their rectum. Attached wire terminals were readily available to plug into a readout device to provide instant body temperature at the first sign of heat distress. This trial seemed strange at the time.

In March 1964, a Gurkha battalion in Borneo contacted a force from the 328 Raider Battalion made up of regular Indonesian army troops. The Raiders eventually holed up in caves in a cliff face and this led to the only use of offensive air power in the campaign. Wessex helicopters of 845 Naval Air Commando Squadron fired anti-tank missiles into the caves. In July, there were 34 Indonesian acts of aggression indicating the scope of confrontation was expanding. In August there was a landing on the mainland of Malaysia in Johore. A force of around 75 Indonesian Marines and army troops with about 25 remnants of the Malaysia CT’s crossed the Malaccan Straits in boats. Within a few days, most of the invaders were killed or captured by the Malaysian Army. This landing on the mainland proved to be the last straw and the British Government agreed to take the fight to the enemy. The Director of Borneo Operations, Major General Walker was authorised to conduct aggressive covert operations up to 5,000 yards across the Indonesian border. These were known as Claret operations.

The ante was also raised internationally at sea when the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious and two destroyers sailed through the international waters of the Sunda Strait en route to Australia, giving two days notification to the Indonesians. Indonesia reacted shortly after, by prohibiting the return journey to Singapore in mid-September. Infuriated by this affront to British prestige, the British cabinet favoured sending them back through these international waters.

There were some concerns whether the carrier group was defensible, but the prevailing opinion was to not do so would be a huge political defeat both domestically and internationally. Offensive air and sea operations were under active consideration, but fortunately, the Indonesians proposed a way out by announcing the carrier group could return via the Lombok Strait. The British cabinet records of the discussions of this incident make fascinating reading, as there was consideration of sending the two destroyers alone to force the Strait as they were far more expendable than the fleet carrier. In the event the British reinforced the carrier group with three more escort vessels and returned via the Lombok Strait and face was saved on both sides.

September 1965 was an interesting month. Three Indonesian C130 Hercules aircraft left Jakarta on 2 September to drop paratroopers into Labis, Johore, about 100 miles north of Singapore, but in the event only two reached the target. One aircraft crashed into the Straits of Malacca while trying to evade interception by a Gloster Javelin aircraft from 60 Squadron based at Tengah in Singapore. Electrical storms caused the drop to be dispersed from the other two aircraft resulting in troops landing close to the 1/10 Gurkhas who were soon joined by the New Zealand battalion rushed down from Malacca. However, it took over a month to either kill or round up the 96 invaders.

Also on 2 September, 3RAR again deployed to the Malay-Thai border in search of CT activity. This deployment was by a troop train and was meant to be secret. However, on arrival mid-afternoon at the Ipoh railway station, the band of the Queens Royal Irish Hussars was on the platform to entertain the troops while they stretched their legs and had afternoon tea. After this pleasant sojourn they re-boarded the train and the Intelligence Officer rode in the cab of the locomotive to tell the driver where to stop for each company to detrain. Once the train had stopped in the night, a company would jump onto the tracks and silently move into the jungle in single file to the patrol area. All went well for the first 30 minutes until platoons went close to a native kampong and all the dogs started barking. So much for the secrecy! Thirty-seven suspects, mainly smugglers, were taken into custody during this operation.

While three companies were deployed to the Thai border, one company was retained in Terendak for Operation Lurgan. This required a force to be on four hours’ notice by day and 30 minutes by night as a mobile reserve to react against incursions. On the night of 28 October 1964, Indonesia landed a raiding group of some 50 troops at the mouth of the Kesang River south of Terendak.

Troops from 3RAR, 1 RNZIR, 102 Field Battery of the Royal Australian Artillery acting as infantry, and a squadron of armoured cars from the 4 Royal Tank Regiment cordoned off the area under the command of the Commanding Officer 3 RAR. An outer cordon of the 1/10 Gurkha Rifles and the remainder of the NZ battalion was also set in place. Twenty infiltrators surrendered on the first day and the remainder tried to break out that night. Small arms fire from the cordon prevented this. Next day a graduated response commenced, beginning with loudspeakers from light aircraft calling on them to surrender. A few rounds of mortar fire followed which then elevated to artillery fire. This proved effective as all but 2 of the infiltrators surrendered. The last 2 were captured by local civilians some 3 weeks later. The action was known as “Operation Flower”.

Subsequent landings on mainland Malaysian soil brought Indonesia and Malaysia and its Commonwealth allies close to war. Up until now the units involved had all been drawn from those based in the Far East, but in January 1965 the first of the UK based units, the Gordon Highlanders and the 2nd Parachute Battalion, together with an artillery regiment, were sent out. At the beginning of 1965, there were 9 British and 3 Malay battalions in Borneo. Indonesia had deployed even larger military forces on the borders which the British could not match. Chief of Naval Staff, David Luce stated “the Indonesian supply of brigades was greater than our supply of battalions”. Instead of upping the ante with more forces, the covert Claret operations were authorised to penetrate even deeper and up to 10,000 yards across the border.

Throughout Confrontation, Britain had considered air and sea strikes against Indonesia and detailed contingency plans were developed. Plan Florid was for air attacks on 18 select targets. Plan Addington was to destroy the Indonesian air strike capability, and Plan Althorpe was designed to wipe out the Indonesian air force and navy. Vulcan bombers deployed from the UK to Butterworth (Malaysia) were surrounded by special RAF guards and brightly lit up at night, giving an indication of the armament carried. In retrospect, the necessity for the earlier NBC suit trials can be understood.

The other consequence of these landings on the mainland was that in early 1965, both Australia and New Zealand finally agreed to the deployment of combat forces to Borneo. This was to be 3 RAR and 102 Field Artillery Battery from Malacca, and 1 SAS Squadron from Australia. It was also an anxious time for families living in married quarters outside the protection of Terendak Camp. Curfews were imposed at night and armed guards were placed on commuter buses to the camp. Private vehicles were subjected to searches at security check points placed on frequent intervals along the roads. The hospital, banks, groceries and recreational facilities were all based in the camp so regular trips by road were a necessity. Indonesian landings along the coast near the married quarters were also a possibility, and many of the beaches were barb wired off and regularly patrolled, all adding to the tension.

Borneo Operations

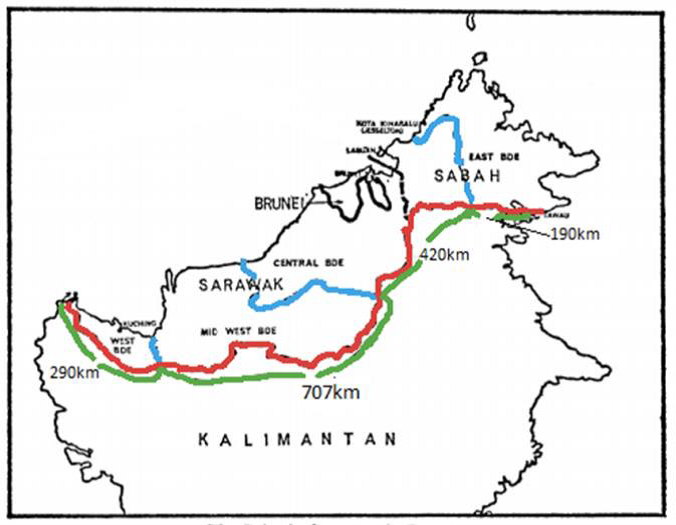

The area of operations in Borneo was divided into four brigade areas controlled from a joint headquarters on Labuan Island. West Brigade, covering the approaches to Kuching, had a front of some 290 kilometres. Mid-West Brigade had two battalions to cover a 707 kilometre front. Central Brigade had two battalions to cover 420 kilometres, and East Brigade had two battalions to cover 190 kilometres. The bulk of the Indonesian forces were concentrated opposite West Brigade area. West Brigade was covered by five battalions and 3RAR was assigned to relieve the 1/7 Gurkha Rifles on 23 March 65.

Troops moved by truck to Singapore for billeting in Nee Soon Barracks were issued with live ammunition and given final orders. The next day they flew from Changi Air Base to Kuching in a mixture of Beverly, Hastings and Argosy aircraft flown by RAF Transport Command. On arrival in Kuching they were immediately transferred to Belvedere helicopters and flown to a forward operational base. The previous year the tactics had changed from platoon bases to company bases, each with a single 105mm gun from 40 Light Regiment Royal Artillery co-located within the base. In 3RAR’s operational area there were three forward company bases, Stass and Serikan, where Charlie Company was based, and Bukit Knuckle. A fourth company was kept in reserve with the battalion headquarters at Bau. On average each forward company was covering around 7 kilometres of border and was about 1,500 metres from the border. There were no roads forward to the company bases so re-supply was by both air drop and helicopter. During our deployment, military engineers built a road forward from Bau. Forward companies were also assigned Iban (indigenous tribes people) trackers who were armed with shot guns.

The changeover with the Gurkhas was being covered by A Company, 3 RAR, three platoon patrols of which had been deployed in advance. As we were flying into the forward base Serikan, we heard on the radio that one of these patrols, 3 Platoon, was in contact with the enemy. On landing, the contact was clarified as being a mine incident. The platoon required immediate casualty evacuation and relief as their commander had been killed. Within the hour 7 Platoon (my platoon) was moving out through the jungle to conduct the relief. A heavy rain squall commenced and by late afternoon we met up with the platoon, which was then being commanded by a corporal. The whole platoon was in battle shock, carrying the bodies of Sergeant Weiland and Tracker Jali in ponchos slung under bamboo poles. There were also two walking wounded, so a clearing was found, and they were evacuated by helicopter just on last light. The two platoons then harboured together for the night. Not much sleep occurred. The next day 3 Platoon continued their withdrawal to the company base, carrying out the bodies of those killed, and my platoon resumed patrolling to the site of the incident.

The mine incident had occurred on a trail at a border crossing point along a ridge line. I had received a brief description of the area from the 3 Platoon corporal. As we suspected there could be more mines, we gingerly made our way forward. We recovered some items left behind, including Sergeant Weiland’s foot still in his boot. Machine gun fire was heard from just over the border, so I called in fire and a few rounds of 5.5 in medium artillery were fired. This was reported the next day in the Straits Times as “Aussies blast Indons”. It was the first public press release on Borneo operations, for both propaganda purposes and to let the world know the Aussies were in the fight. Four American made M2A4 jumping jack mines were later cleared by an engineer team with the platoon that relieved us. Torrential tropical storms were frequent − Borneo receives some 3,000 millimetres of rain per year. During one such storm all the claymore mines and flares surrounding a company base were set off by lighting − much to the confusion of the base occupants who thought they were under a massive attack.

For the next month or so the battalion conducted constant ambush and reconnaissance patrols along the border. At any one time, each of the company bases had two platoons out and one platoon in base rotating every four days. This time was not without its incidents. The importance of patrol coordination was brought home when a relieving patrol clashed with another patrol returning to base. The returning patrol (8 Platoon) had reported that it was at a certain position along a ridge line way past the position the relieving patrol (my platoon) was to climb to on the ridge. As we proceeded along the ridge, the forward scout observed movement ahead. Contact was reported by radio and a hasty ambush established. The forward scout opened fire, and fire was returned. At the same time 8 Platoon reported contact. After a short period of confusion, it was established that this was a friendly fire incident and a cease fire was called. Unfortunately, my platoon’s forward scout had wounded a member of 8 Platoon in the initial burst of fire. The other platoon was livid, and we had to quickly separate the two platoons before a fight broke out. My platoon took over their wounded soldier and evacuated him by helicopter while the other platoon continued to withdraw to the base (perhaps to brush up on their map reading)!

At the end of April, 3 RAR mounted their first Claret operations and sent patrols across the border. General Walker was initially authorised to conduct patrols up to 5,000 yards, later extended to 10,000 yards across the border. These secret patrols were conducted under very strict rules − deniable, no smoking, cooking or washing, no ID discs worn, all operations rehearsed. Operation Achilles conducted by 5 Platoon , B Company, successfully ambushed four boats each carrying five armed men on the Sungei Koemba on 27 May. Two more successful ambushes occurred in early June. The first, Operation Faun, was another ambush on the banks of the Sungei Koemba conducted by 7 Platoon, C Company. Accompanying this patrol were the company commander, the intelligence officer, and a NZ artillery forward observer. Although they were all senior to me, the company commander had stressed during rehearsals that the platoon commander was the sole commander, and this remained so. The company commander and intelligence officer were present to participate in the action because the intelligence that the patrol was based on was extremely good. SAS patrols had reported on the amount of river traffic, and radio intercepts confirmed the high level of enemy activity in the area.

During the first day in ambush five boats were allowed past as they were manned by civilians. The following morning while lying in ambush, an enemy party was observed moving along the riverbank on the left flank of the platoon. The enemy were engaged and at least 3 were killed. The enemy continued to advance threatening the rear of the ambush and the company commander, acting as a rifleman, killed 2 more. The platoon commander gathered the nearest troops to him and this party counter attacked the enemy, killing 3 more. One enemy was seen to be running away and despite long bursts of accurate Owen gun fire, escaped. Eight enemy were killed, one seriously wounded and another escaped.

On searching the bodies, it was noted that some of the 9 millimetre rounds from the Owen gun were imbedded in the webbing of the troops, possibly explaining the luck of the escaping enemy. These two contacts were not officially recorded in the War Diary.

Three days later, on Operation Blockbuster, 2 Platoon, A Company, sprung a large ambush killing at least 17 but possibly 50. The range of casualties was due to a large number of artillery rounds fired on to the ambush site. This patrol had suffered 2 wounded and the casualties meant that it could not be kept secret, so it was reported as having occurred ON the border.

After these successful actions, a halt to Claret operations occurred to see what the Indonesians would do. Things seemed to quieten down for a while.

The halt to the Claret operations did not last long, as in late June the Indonesians mounted a significant attack on a base in Plaman Mapu occupied by B Company, the 2nd Parachute Regiment. Three Indonesian platoons attacked the base during a monsoonal rainstorm while most of the company was out on patrol. The base was occupied by elements of Company HQ, a mortar section, and an under-strength platoon, under the overall command of the Company Sergeant Major. The Indonesians penetrated the base but were driven out and a close quarter battle ensued. Fifty Indonesians were killed in the action and two paratroopers were killed.

There was also an attack against a police base around this time, which led to Claret operations being resumed. Two weeks later, on 12 July, the fourth and last successful ambush conducted by 3 RAR occurred at Babang in Kalimantan. Babang was an Indonesian base with well used tracks in and out. An ambush, again by 7 Platoon, C Company, was set up along one of the tracks and the forward elements of a force of around 30 Indonesians entered the ambush site. The intelligence officer was again accompanying my platoon, and he prematurely sprung the ambush when he felt he had been observed by one of the Indonesians. The remainder of the enemy force counter attacked from the flank and mortar fire commenced from the nearby base. A fighting withdrawal was commenced, and the platoon leaped frogged sections to extricate itself successfully, without suffering any casualties. At least 13 Indonesians were killed and another 5 wounded. This contact also was not officially recorded in the War Diary. The Indonesians retaliated with a large-scale mortar attack against the forward company base at Stass.

Two weeks later, the battalion was relieved by the 2/10 Gurkha Rifles and the battalion was lifted directly from the forward bases by helicopters to HMS Albion. After a three-day voyage, the Albion arrived off Malacca and the battalion stormed ashore in assault landing craft. Standing on the beach were senior staff officers and families to welcome them home.

A custom had developed that a large bottle of whisky was presented to the platoon that had a contact so that they could celebrate in style. This was passed from platoon to platoon and I carried it home empty to Malacca.

The battalion resumed strategic reserve duties in the protection of mainland Malaya for the next two months. On the night of 30 September an unsuccessful communist inspired coup took place in Jakarta. Six senior generals were killed, but the coup failed overall and was followed by widespread violence and bloodshed. This was the turning point for Confrontation from a broader political point of view as a regime change was underway in Indonesia.

The End of Confrontation

In early October 3 RAR was relieved by the newly raised 4 RAR and returned to a base in the Adelaide Hills at Woodside in South Australia. When the battalion was withdrawn from Borneo, 1 SAS Squadron was also withdrawn and returned to Australia. During the SAS’s tour they suffered only one casualty when a member of a four-man Claret patrol was gored by an elephant and died of his wounds. The squadron had at least three separate contacts killing some 15 Indonesians.

Feints against the mainland and crossings in East Malaysia ebbed and flowed. A significant action occurred on 21 November 1965 involving the 2/10 Gurkhas who had relieved 3 RAR. An Indonesian company of paratroopers infiltrated to the rear of the Company bases and entrenched themselves near the HQ at Bau. The Gurkhas mounted a company attack during which L/Cpl Limbu distinguished himself on three occasions. For his actions L/Cpl Limbu was awarded the Victoria Cross, the only one awarded during the entire Confrontation. Twenty-four Indonesians and 3 Ghurkhas were killed in the action.

4 RAR’s service in Malaysia followed a similar pattern to that of 3 RAR in that the first six months were occupied with brigade exercises for their strategic role. In April 1966 the battalion deployed to Borneo and took over from the 1/10 Gurkha Riffles in an area almost the same as the positions occupied by 3 RAR. At the same time, peace discussions had begun between Malaysian and Indonesian officers. While the negotiations were going on, the British ensured that they remained on the Malaysian side of the border but there was a fear that the Indonesians were taking advantage of the lull to increase their training of infiltrators. These fears were not unfounded. In June two large parties infiltrated into the Bau area, and 4RAR together with the neighbouring 2/7 Gurkhas were deployed to cut off their return routes. The withdrawing enemy forces were contacted twice in different locations resulting in the enemy losing four killed and two wounded. Unfortunately 4 RAR lost one killed and one wounded in these actions, and 2 Gurkhas were wounded by an SAS patrol in a friendly fire incident. The Gurkhas also intercepted the infiltrators, killing 3 and wounding 3.

The final Indonesian incursion occurred in May-June 1966 in the Central Brigade area. A force of some 80 Indonesians was pursued by 1/7 Gurkhas who accounted for most of the invading force.

On 28 May 1966 the Malaysian and Indonesian Governments announced that Confrontation was over, but vigilance was maintained in Borneo until it was clear who was in charge in Indonesia. This became clear when a peace treaty was signed on 11 August 1966 after General Suharto came to power. Confrontation was truly over.

During Confrontation, a total of 114 British and Commonwealth servicemen were killed and 181 were wounded. Of these, Australia lost 16 killed and 9 wounded. 3RAR lost 3 killed in action all by enemy mines. Indonesian casualties were 590 killed, 222 wounded and 771 captured.

It should be noted that Claret operations played a very important part in Konfrontasi and remained secret from the public until acknowledged by the British Government in 1980 and finally by the Australian Government 31 years after the event in 1996. They remain little known to this day.

References:

1. Horner, David (1990), Duty First – The Royal Australian Regiment in War and Peace

2. Wells, Norm, Operation Flower – The Battle of Sungei Kesang

3. Wikipedia, “Claret Operations”, “The Battle of Babang”, “The Battles of Sungei Koemba 1 and 2”

4. Smith, Neil (1999), Nothing Short of War: Borneo 62-66

5. Australian War Memorial (1996), Official History Vol V: Emergency and Confrontation

6. Australian War Memorial – photographs and website

Colonel Bob Guest (Rtd), is a Graduate of the Canadian Forces Staff College and the Joint Services Staff College, he holds an Honorary Fellowship with the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists. First published in MHSNSW Reconnaissance, Autumn 2020

Contact MHHV Friend about this article.