Odds are that you have heard of Simpson and his donkey. And maybe you know that pigeons were used extensively to transport messages in World War I. There is an extremely strong chance you know something about the Light Horse Brigade. So what do they all have in common? Perhaps it’s the bond of a human and an animal in dangerous times?

Curator of the ‘A is for Animals’ exhibition at the Australian War Memorial, Kate Dethridge, says that animals’ companionship and instincts were of particular note: ‘We have a lot of stories of animals, particularly from the Second World War, of animals who would be like an early warning system to soldiers of air raids and that sort of thing.’ HMAS Perth in World War II had a mascot cat named Red Lead which is assumed to have gone down with the ship when the HMAS Perth was destroyed by a fleet of Japanese ships.

Many animals were trained in Australia for use in conflicts overseas. However with Australia’s strict border quarantine policy it was often impossible, until recently, to return them home. Ten black Labrador-cross tracker dogs were left with western families in Saigon. Despite public donations and pleas to bring the dogs back from Vietnam the authorities never seriously entertained the idea – something which still cuts very deeply with the men and women who worked with and knew them

In the First World War between 136,000 and 169,000 “Walers” (the name generally applied to Australia’s sturdy horses) were sent overseas for use by the Australian Imperial Force and the British and Indian governments; 6,100 of those horses embarked for Gallipoli. The Anzacs’ Walers performed their difficult carrying tasks magnificently despite the stress of gunfire and lack of water at Gallipoli, and were the beloved mounts of the famous Light Horse regiments. Soldiers slept with their horse to stay warm on freezing nights in the desert and their steeds were often hungry enough to eat each other’s tails. But they were mostly killed or passed on to other military units abroad at the end of the war because of the costs and quarantine difficulties involved in repatriation.

Some historians have fuelled the belief that almost all of the 9000 horses left behind in Palestine by the Australian Light Horse were either shot or ‘sold into slavery.’ Those mounts aged over 12 or in poor health were certainly destroyed, many by their own troopers. Yet veterinary returns filed at the AWM suggest that approximately two-thirds of the horses were transferred to Imperial, mainly Indian Army cavalry to continue their working lives. Perhaps their fate was not as dreadful as commonly supposed. One horse from them all made it back to Australia.

Over 10 years ago the RSPCA first approached the AWM with the idea of a memorial for animals involved in the Australian armed forces. Canberra artist Steven Holland designed the animal memorial utilising a bronze horse head which was originally a part of a memorial dedicated to the Australian Light Horse Brigade and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles in Port Said, Egypt, designed by Charles Webb Gilbert in 1923 and unveiled by Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes in 1932.

The statue was attacked and destroyed by Egyptian rioters During the Suez conflict on December 26, 1956, and the remaining pieces were returned to Australia and became part of the AWM’s collection. Now, the Australian War Memorial has unveiled the statue to honour all the service animals – the bronze horse head, mounted on a tear-shaped granite plinth is placed in the memorial’s sculpture garden.

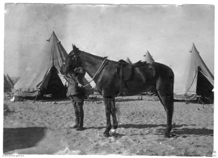

There is still much debate about the need for another statue, a special monument in a special place for just one special animal. “As the only horse to come back, he deserves a memorial. He stands as representative of all of Australia’s war horses” said ‘Friends of Sandy and the Australian Light Horses’ Honorary Secretary Alan Ross, whose father Andrew George Ross was in the 4th Light Horse machine gun section and who fought at the Battle of Beersheba. Sandy, a 16-hand chestnut, was the only war horse to return of over 136,000 and November 2009 marks the 90th anniversary of his return to Australia, after a tour of duty which included the coast of Gallipoli, Egypt and France.

Sandy was one of three horses assigned to the commander of the Australian 1st Division, Major General Sir William Bridges. The Australian 1st Division was the first ashore at Gallipoli. However, very few of the animals were put ashore, as Lieutenant General Sir William Birdwood decided there was not room or requirement on ANZAC Cove. On 5 May Birdwood sought approval to send the horses back to Alexandria. General Bridges died on May 18, 1915 from wounds he received three days’ earlier when shot by a sniper in Monash Valley at Anzac Cove. Major General Sir William Bridges was buried at Alexandria before he was exhumed and honoured with a state funeral in Melbourne and then on 3 September 1915 re-buried at the Royal Military College in Duntroon, Canberra on the slopes of Mount Pleasant.

Sandy, who was presumed to be offshore at the time of Bridge’s death, was eventually shipped back to Egypt. It was the dying wish of General Bridges that Sandy be returned to Melbourne at war’s end. From 1 August 1915 Sandy was in the care of Australian Army Veterinary Corps office Captain Leslie Whitfield in Egypt. Sandy remained in Egypt until he and Whitfield were transferred to France during March 1916.

In October 1917 Senator George Pearce, Minister for Defence, called for Sandy to be returned to Australia for pasture at Duntroon. In May 1918 the horse was sent from the Australian Veterinary Hospital at Calais to the Remount Depot at Swaythling in England. He was accompanied by Private Archibald Jordon, who had been at the hospital since April 1917 and classed as permanently unfit for further active service. After three months of veterinary observation, Sandy was declared free of disease. Copies of the ensuing letters, cables, minutes and memos between the organising parties are now preserved as part of an official record AWM13 7026/2/31 in the memorial archives.

In September 1918 Sandy boarded the freighter Booral, from Liverpool, arriving in Melbourne in November. Sandy was turned out to graze at the Central Remount Depot at Maribyrnong, a stretch of land in a bend of the Maribyrnong River that was the staging point for horses bound for the wars. Although he was originally intended to go to Duntroon, the official record says he was “pensioned off”, or turned out to graze for the next six years at Remount Hill, the home and training ground of the Light Horse Brigade. With age Sandy’s eye sight failed, and his growing debility prompted the decision to have him put down, “as a humane action in May 1923.

Sandy’s proud head and neck were mounted  and became part of the Memorial’s collection. Recently restored he is currently on display as a feature part of the ‘A is for Animals’ exhibition. A legend among war horses, his hooves were mounted and used as paperweights and inkwells at Duntroon House. His carcass was buried somewhere in the paddock, believed to be not far from the remount headquarters. The now unmarked and unknown exact spot is part of the 127-hectare former explosives depot sold by the Defence Department to become one of Melbourne’s newest $1 billion suburbs.

and became part of the Memorial’s collection. Recently restored he is currently on display as a feature part of the ‘A is for Animals’ exhibition. A legend among war horses, his hooves were mounted and used as paperweights and inkwells at Duntroon House. His carcass was buried somewhere in the paddock, believed to be not far from the remount headquarters. The now unmarked and unknown exact spot is part of the 127-hectare former explosives depot sold by the Defence Department to become one of Melbourne’s newest $1 billion suburbs.

Since 2000, a group of Maribyrnong residents, led by Keith Ashton and Alan Ross, have run a “Friends of Sandy” campaign to see a fitting memorial for the horses created on the hill. They want the exact location of Sandy’s remains pinpointed ahead of the massive redevelopment Alan Ross, as a boy, used to deliver papers there during World War II, and he remembers the place abuzz with horse-centred activity. “The fact they were trained and lived at Maribyrnong before being shipped off makes it the most appropriate site for such a statue to stand,” said Mr. Ross.

The land, now heavily contaminated and requiring a massive clean-up, became the first Commonwealth explosives factory in 1910. The Maribyrnong hilltop contains only the concrete floor remains of the remount headquarters and horse hospital. The buildings were demolished after they fell into disuse following World War II. The munitions factory closed in 1994. VicUrban expects to integrate some of its historic buildings in its new development.

First the contaminated land must be cleaned in a process expected to start next year, take two to three years and cost at least $75 million.

Information provided by the Parliamentary Library to Maribyrnong MP Bill Shorten says the explosives factory had left the land contaminated with nitrates, cyanide, heavy metals and chlorinated hydrocarbons. It eventually will have 3000 homes, including 600 for public and social housing tenants. The State Government developer VicUrban said via spokespeople that Sandy will be honoured in Melbourne’s newest suburb.

Alan Ross has old photos showing how the heavy gun was strapped to one horse and the magazine of ammunition to another horse behind as both were led into battle. Mr. Ashton said the hilltop needed to become a historical park with a sculpture that commemorated the horses — either a copy of an existing grand piece in Canberra or a newly commissioned one.

Images from the Australian War Memorial.

Contact Jason McGregor about this article.