Plans, Command Problems and Controversy.

This paper is based on a chapter that I co-authored with my PhD supervisor, Professor Peter Stanley from the University of NSW Canberra, and which appears in the book Australia 1944-1945, edited by Dr Peter Dean of the ANU. I thank both of them for their assistance.

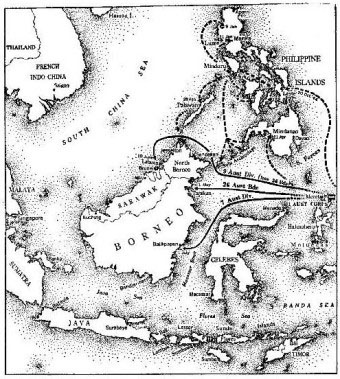

The campaign for the island of Tarakan, off the north-east coast of Borneo, was the first of three major landings in Borneo by the I Australian Corps. This series of operations were known by the code name ‘Oboe’, with the Tarakan landing known as Operation ‘Oboe 1’.

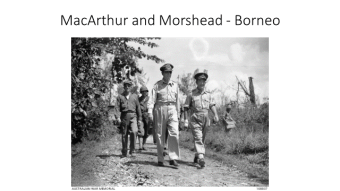

General Douglas Macarthur, the Commander-in-Chief of the South-West Pacific Area, originally intended Oboe 1 to be the first of a series of operations down the east coast of Borneo that were to culminate with the seizure of Java – the main island of the Netherlands East Indies. But as a result of a complex series of political and strategic arguments and decisions, the Oboe series of operations was modified to focus on the capture of Borneo’s oilfields. Macarthur argued, somewhat dubiously, that Borneo oil would have been needed to supply his forthcoming massive invasion of Japan.

This wider strategic debate about the origins and value of the Borneo campaign as a whole is a larger subject than this paper can encompass. The point is that, in the end, MacArthur decided that the Borneo campaign would include the following operations: Oboe 1 – the seizure of Tarakan on May 1st, 1945; Oboe 6 the capture of Brunei Bay on June 10th; and, Oboe 2 – the landing at Balikpapan on July 1st, 1945.

MacArthur therefore instructed the commander of I Corps, Lieutenant General Sir Leslie Morshead, to seize Tarakan, destroy the Japanese garrison, re-establish the Netherlands East Indies administration, and conserve the island’s significant oil installations. But most importantly, as soon as the island’s airfield was repaired, it was planned that seven RAAF squadrons of Kittyhawks, Spitfires and Beaufighters would move in to support the next two landings at Brunei Bay and Balikpapan.[1]

The Borneo Campaign 1945

Morshead, allocated the 26th Brigade Group of the 9th Australian Division to assault Tarakan. In contrast to earlier Australian campaigns, the Oboe operations would receive lavish support from Allied air and naval forces. Despite this, Oboe 1 would prove to be far more difficult – and controversial – than expected.

As the primary purpose of the Tarakan operation was to seize the island’s air strip and to develop it as a base to provide air support for the following Oboe landings, this paper focuses on the how the RAAF planned and executed its role and what was achieved at the end of the day.

Tarakan Overview

Before getting into the detail of what the RAAF did, let me first provide a brief overview of the Tarakan campaign.

The Oboe One force included some 10,800 troops from the Australian Army, 5,700 RAAF personnel, 130 RAN Beach Commandos, and about 900 Americans and Dutch – a total of some 17,500 men to be landed.[2] The naval task group that carried and escorted the assault force comprised some 120 vessels ranging from cruisers and destroyers to minesweepers and landing ships and landing craft of various types. Eight Australian warships were included in the fleet.[3] It is interesting to note that, at this stage of the war, this was a comparatively small force by American standards.

The day before the assault, April 29th, Australian engineers blew gaps in the beach obstacles that the Japanese had built to stop landing craft from reaching the shore. The sappers were supported an artillery battery landed on a small off-shore island.

On May 1st, after a heavy naval and air bombardment, the assaulting battalions from the 26th Brigade began landing just after 8.00 am. From the moment the troops stepped ashore they encountered Tarakan’s difficult terrain. The island’s so-called beaches were actually composed of atrocious thick, black mud. Seven American LST’s – Landing Ships, Tank – were temporarily stranded on what were in fact tidal mud-flats. Under these conditions, getting tanks, guns, vehicles and other heavy equipment ashore and on to firm ground proved to be very difficult, and resulted in undue congestion on the beach.

The infantry, nevertheless, pushed inland against increasing Japanese resistance around Tarakan township. The airfield was captured on May 5th, but when RAAF engineers inspected it they did not like what they saw. The strip had been severely cratered by allied bombing and apparently had been abandoned several months earlier by the Japanese. Moreover, it was badly waterlogged and there were mines everywhere. In the Oboe 1 plan the original intention had been to have the airfield operational by May 7th – a week after the landing. But, as I will explain in detail later, it proved so difficult to repair that it was not ready until the end of June – some seven weeks later than planned. This was much too late for the next Oboe landing at Brunei Bay on June 10th.

As the RAAF struggled to repair the airstrip, the ground fighting continued. The task was to drive the Japanese off the jungle-covered hills that overlooked the airfield. This involved bitter close-quarter infantry combat of the nastiest kind with the Australians probing forward to detect heavily camouflaged Japanese bunkers, which then had to be assaulted one-by-one. Even with massive fire support, including napalm dropped by B-24 Liberators, the Australian infantry suffered heavily. By the time the fighting finished the 26th Brigade had lost 894 casualties including 225 killed.

As happened on many other battlefields, most of the Japanese garrison fought to the death. Of the 2,100 Japanese on the island, including some 250 civilian workers, only 252 surrendered before the end of the war, and another 300 surrendered after the cease fire. Only a handful escaped to the mainland of Borneo – the rest were killed.[4]

Oboe 1 Condemned

Given the heavy Australian casualties, and the seven-week delay in opening the airfield for operations, it is not surprising that the Tarakan operation has been condemned as a wasted effort. It is usually included in what journalist and historian Peter Charlton called ‘the unnecessary war’ – the title of his book in which he claimed that the 1945 campaigns cost Australian lives to no good purpose.[5] Charlton’s book came out in 1983, but this view can be traced back to the 1950’s and 1960’s when the Australian official histories of the Second World War described the Oboe 1 as an unambiguous failure.

In the relevant Army volume, The Final Campaigns, the official historian Gavin Long concluded that Tarakan airfield ‘proved so difficult to repair that it was not ready in time for the opening of the operation against either Brunei Bay or Balikpapan.’[6] While in the Air Force volume the Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, RAAF historian George Odgers claimed, ‘Since the operation was undertaken primarily for the purpose of establishing an airfield for use against other points in the Netherlands East Indies, Tarakan must be regarded as a failure.’[7] Twenty-two pages later, however, Odgers somewhat contradicted himself, and Long, by stating that on June 30th, 1945 the RAAF ‘now began flying from Tarakan in support of the Balikpapan operation’, that is, a day before Australian troops began landing there on July 1st.[8] He then went on to describe some of the RAAF operations from Tarakan. This got me thinking about what the RAAF actually achieved.

RAAF Command Arrangements and Forces

To fully understand how the RAAF performed during Oboe 1 it is necessary understand how it was commanded.

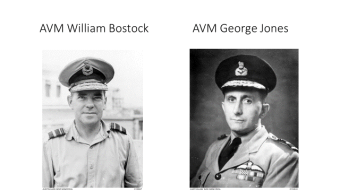

In the lead-up to the Borneo campaign, in a letter dated February 27th 1945, Australia’s Prime Minister, John Curtin, pressed General MacArthur to ensure that the RAAF would take ‘its rightful place in operations in the South West Pacific Area.’[9] Unfortunately, this goal was undermined by the corrosive internal power struggle between the RAAF’s administrative and operational commanders, Air Vice-Marshals George Jones, and William Bostock. Jones was the Chief of Air Staff, while Bostock commanded RAAF Command Allied Air Forces. Jones and Bostock simply could not stand each other. They engaged in a long bureaucratic battle to control the RAAF which, as we shall see, would have a direct impact on operations at Tarakan.

Up to this point, Bostock’s RAAF Command had been responsible for allied air operations from the Australian mainland, including the air campaign over the north-west and the Netherlands East Indies. Following Curtin’s letter, MacArthur agreed that Bostock would establish a headquarters in the forward area and take command of the RAAF outside the mainland as well.[10]

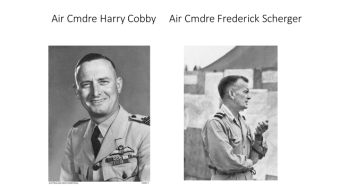

The RAAF’s striking force in the forward area was the First Tactical Air Force (First TAF), commanded by Air Commodore Harry Cobby. He had assumed command in August 1944 after his predecessor, Air Commodore Frederick Scherger, had been injured in a jeep accident. First TAF, and its earlier incarnation, 10 (Operational) Group, had been under American control since 1943, but on April 4th, 1945 it was transferred to Bostock’s RAAF Command.[11] For the first time, all the RAAF’s combat forces in SWPA came under the operational control of an Australian officer – Air Vice Marshal Bostock.

The American commander of Allied Air Forces in SWPA, Lieutenant-General George Kenney, delegated the planning and coordination of air support for the Borneo invasion to Bostock. In addition to First TAF, Bostock commanded the RAAF’s heavy bombers in the Northern Territory and Western Australia. He could also call on the resources of the US Fifth Air Force on Luzon and the US Thirteenth Air Force in the Southern Philippines.

The island of Morotai, which the Americans captured in September 1944, became the forward base for the Borneo landings. Bostock opened his Advanced Headquarters, RAAF Command on Morotai on March 15th, 1945, alongside the headquarters of First TAF and I Australian Corps.

In line with Curtin’s desire that the RAAF should take its ‘rightful place’ in the forward area, Bostock decided that he would reinforce First TAF, which was building-up on Morotai, and reduce his forces in Australia and New Guinea. By April 1945, First TAF had grown into a powerful force with the following units in the field or slated to join:

- nine fighter squadrons

- six attack squadrons

- an army cooperation wing

- nine airfield construction squadrons

- as well as numerous radar, technical, logistic and medical units.[12]

Bostock also earmarked half a dozen medium and heavy bomber squadrons in Australia to move forward as the Oboe landings rolled out and more airfields were captured. By the end of April, First TAF had a strength of nearly 16,900 men. By the end of June it had just over 20,600 men.[13]

But before the invasion of Borneo could get underway, First TAF was rocked by the so-called “Morotai Mutiny”. On April 19th, eight senior RAAF combat officers submitted their resignations because they believed that Cobby’s decision to order regular strikes against bypassed Japanese forces on neighbouring islands had caused unjustifiable losses. Bostock responded quickly, and on April 22nd he recommended that Cobby should be relieved of his command. By this stage Scherger had recovered from his injuries, so Bostock selected him to return to his former command. However, Scherger did not arrive to replace Cobby until May10th. So during the eight days immediately before the Tarakan landing, and for ten days after, First TAF was commanded by an officer that Bostock wanted sacked. The RAAF’s Borneo campaign was off to a bad start, and the problems would continue.

Tarakan as an Air Force Objective

I will look now at how Tarakan fitted into the planning of the air force side of the Borneo campaign.

As mentioned, MacArthur decided that the final sequence of the Borneo landings would be: Tarakan (Oboe 1), on May 1st; Brunei Bay (Oboe 6), on June 10th; and Balikpapan (Oboe 2), on July 1st. While the strategic value of the Borneo campaign has been doubted, this sequence of landings made operational sense in terms of air power. Seizing Tarakan first meant that both Brunei Bay and Balikpapan could be brought simultaneously within the range of RAAF’s long range Beaufighter attack aircraft and short range Spitfire and Kittyhawk fighters – assuming Tarakan airfield could be made operational. In particular, it would have allowed maximum air power to be deployed against the substantial Japanese fortifications at Balikpapan for the longest possible period.

In his report on Tarakan, Bostock noted that RAAF Command had three main tasks: to neutralise any enemy forces that could interfere with the operation; support the 26th Brigade; and, establish air forces at Tarakan to support of the following Borneo landings.[14] According to intelligence estimates, the Japanese had only 48 fighters and 21 bombers in the whole of the Netherlands East Indies, so Bostock could be assured of overwhelming superiority.[15] The experience of the Philippines, however, had shown that Japanese suicide planes could inflict severe damage on allied ships, even if only a handful could sneak through a convoy’s air cover.

Early in the planning phase, MacArthur’s headquarters decided that the air garrison of Tarakan would include a fighter wing and an attack wing.[16] Cobby allocated 78 (Fighter) Wing with three Kittyhawk and one Spitfire squadrons and 77 (Attack) Wing with three squadrons of twin-engine Beaufighters, together with other specialist units.[17] The Oboe 1 plan anticipated that the Tarakan airfield would be ready to receive its first aircraft from May 7th – just a week after the landing.[18] To achieve this, two RAAF airfield construction squadrons of 61 Airfield Construction Wing would land immediately after the 26th Brigade and start work on the strip as soon as it was captured. The wing included 1 and 8 Airfield Construction Squadrons, which were specialist engineer units with heavy construction equipment. Airfield construction squadrons could also defend air strips as they built them. To coordinate these forces the Advanced Headquarters of First TAF would sail with the assault convoy.

During April, as planning proceeded for the establishment of a RAAF force on Tarakan, Bostock co-ordinated a series of preliminary air operations. American bombers from the Philippines and a detachment of RAAF Liberator heavy bombers from Morotai carried out the pre-invasion bombardment of Tarakan. In addition to bombing Japanese emplacements and troop concentrations, the airfield was bombed heavily and repeatedly to keep it out of action. Meanwhile, for 20 days before the landing RAAF Liberators from the Northern Territory and Western Australia struck at targets elsewhere in the East Indies as part of the wider effort to isolate Borneo.

The Tarakan landing began on May 1st, 1945. Part 2 will exmine how the RAAF performed during the operation.

Click here for Part 2

[1] Gavin Long, The Final Campaigns, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1963, p. 406

[2] Long, The Final Campaigns, p. 407; Peter Stanley, Tarakan: An Australian Tragedy, Allen & Unwin, Sydney 1997, p. 41; G. Hermon Gill, Royal Australian Navy 1942 -1945, Australian War Memorial, 1968, p. 623

[3] Gill, Royal Australian Navy 1942 -1945, p. 620

[4] Long, The Final Campaigns, p. 451

[5] Peter Charlton, The Unnecessary War: Island Campaigns of the South-West Pacific 1944-45, MacMillan, Melbourne, 1983

[6] Long, The Final Campaigns, pp. 451-52

[7] Odgers, Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, p. 461

[8] Odgers, Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, p. 483

[9] ibid, p. 437

[10] ibid pp. 438-39

[11] NAA A11093 320/5K4, RAAF units under Operational Command of American Air Forces. Bostock decided to change the name of 10 (Operational) Group to First TAF in 1944 to better reflect its role and growing size and because in the USAAF a ‘group’ was a unit of only three or four squadrons.

[12] NAA A11225 224/8/Org, Organisation Memorandum – 1st TAF RAAF, 4 April 1945

[13] Odgers, Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, p. 439 and p. 477

[14] NAA 1966/5 383, RAAF Command Report of Oboe One Operation, p. 2

[15] Odgers, Air War Against Japan 1943-1945, p. 452

[16] AWM 3DRL 2632, Morshead Papers 7/6, “Montclair” Basic Outline Plan for the Reoccupation of the Western Visayas-Mindanao-Borneo-NEI Area, 3rd Edition 25 February 1945

[17] Cobby originally allocated 81 (Fighter) Wing at Noemfoor for the task. However, it could not be brought forward in time so 78 Wing at Morotai was substituted, although it had only ten days’ notice. Odgers p. 453

[18] Gary Waters, Oboe Air Operations Over Borneo 1945, Air Power Studies Centre, Canberra, 1995, p. 53

Contact Tony Hastings about this article.