There has existed for many years a persistent myth that the first air attack on Darwin, on 19 February 1942, has been concealed by the federal government, a tale perpetuated even in modern times.

A newspaper of 2012 slams the wartime administration: “An embarrassed official wall of silence sprang from John Curtin’s government’s belief that the less the public was told, the better.”

A curriculum project for modern schoolchildren headlines a major section “The Cover Up” and advises:

The day after the first bombing of Darwin the southern newspapers claimed that 15 people were killed and twenty four hurt. The later Royal Commission came up with an official death toll of 243 killed and 300 wounded.

The dichotomy is not portrayed as ironic, even though the second quotation dispels any idea of “cover-up” and the numbers are reasonably accurate.

Modern websites continue the claim. The “educational materials” website SKWirk advises: “The Australian public was never informed about the response of the Darwin population and defence personnel.”

Another advises, without any source for the claim, that: “The damage and disaster was on such a huge scale that for days, weeks, months, years and even decades after the bombings, the full extent of the catastrophe was hidden from the public.”

Even an Australian government educational website alludes to the concept, without sources:

At the time, there were many rumours alluding to the Australian Government’s suppression of information about the bombings – it was thought that reports of casualties were intentionally diminished to maintain national morale.

“Answers.yahoo.com” hosts the rather ungrammatical question: “Why did the Australian government conceal the correct death toll from the bombing of Darwin? 19 February 1942, the Japanese bombed Darwin, Australia. The Australian government concealed the real death toll from the public, why was this?”

Their answer says:

Knowledge of the attack on Darwin would have caused panic around Australia, and have a demoralising effect on the public. In order to stop this happening, the Government imposed censorship on all news concerning Darwin, and many people didn’t find out about the bombing until long after the war was over.

During the war years the government controlled what was printed and spoken in the media. This censorship was necessary to ensure that no sensitive information was available to the enemy. So, as well as keeping public order, suppression of news of the Darwin attack was aimed at making the enemy feel they’d made little impact on Australia.

The website of the Darwin Defenders, a group of ex-military dedicated to recognise those who served in the area during the war, advises that “Despite a Royal Commission into the attacks, for years the Australian government suppressed the truth about casualties and damage.”

In researching our new book Carrier Attack, we found the only problem with all of these claims is that government didn’t cover up much at all, and it certainly did not cover up the full impact of the raids. Nor was there any attempt to supress information through the decades that followed, for any citizen wishing to investigate the relevant government reports and files. So why has the impression arisen that there was a plot or similar machination to keep the information from Australians? The answer, as will be revealed below, is simple: the Darwin raids and indeed the war of northern Australian, which consisted of submarine warfare and over 100 air raids, was never taught beyond faint echoes in the nation’s schools.

On the day following the attacks the Canberra Times highlighted the attack on its first page. It was not a very accurate report but it could hardly be said to be a cover-up. It read:

Heavy Japanese Blows On Darwin Large Bomber Forces In Two Raids

Cabinet’s Grave View Damage Considerable: Casualties Not Known

SYDNEY, Thursday.

Two Japanese raids were made on Darwin to-day by forces of twin engined bombers, and considerable damage is reported to have been occasioned. In the first raid this morning, which lasted for an hour, 72 enemy twin engined bombers accompanied by fighters participated, and in the second raid 21 bombers took part. Four enemy aircraft are known to have been brought down.

In a statement at 10.43 p.m., the Prime Minister (Mr. Curtin) said: “Further advice has been received regarding the attack on Darwin. There was another raid this afternoon. Damage was considerable and reports to hand so far do not give precise particulars as to loss of life.

“The first attack was made by 72 twin-engined bombers accompanied by fighters. In the second attack, 21 twin engined bombers took part.

“It is known for certain that four enemy bombers were brought down.

“The Government regards this attack as most grave and makes it quite clear that a severe blow has been struck on Australian soil.

Photographs of this newspaper and the others cited here are easily available at the National Library of Australia Trove website. Dozens of other newspapers reported the same story, more or less. Although the first raid bombers did not have “twin engines” – those in the second raid did though – the raid was definitely reported.

In the following day’s edition the same newspaper reported 15 people killed and 24 injured. While this is hardly accurate it reflects the slow lead times and reporting methods of those days, without email, faxes, and utilizing scarce and expensive telephones and telegrams. Further, those in charge of Darwin were hardly going to be concerned with reporting lists of the dead. Unlike present times, the armed forces of Australia and America did not have large departments concerned with reporting the war for newspapers’ benefits, and providing suitable photographs or “imagery” as it’s called today.

By the 24th the Canberra Times was reporting Prime Minister Curtin as saying that he “did not propose to inform the Japanese of the degree of the success or failure of their attack.” This was a rather sensible precaution to take. By 28 February newspapers such as the Adelaide Mail was reporting details of the raids complete with a map showing the (correct) direction of the Japanese attack from the south-east. Scores of stories were appearing in a myriad of newspapers around Australia, in particular small anecdotes from survivors. On 3 March The West Australian carried a story about the “70 bombers” which had attacked Darwin. The following day the Townsville Daily Bulletin cited 90 planes in a melodramatic style:

Pat Murray, a plumber, said that as a donkey engine driver named Cardow saw a bomb dropping toward him, he called out, ‘Good-bye boys, see you in the next world.’ He was killed. The bombs razed all trees in front of the Administrator’s house. Raymond Brooks, one of the evacuees, was met by his wife and had to tell her that her father, Mr. C. Spain, and her Uncle had been killed. Spain was machine gunned and his body hurled into the harbor by a bomb blast. John Cubille [sic] was killed, leaving a widow and seven young children. William Harris, laborer, said it was hell let loose when the Japs came over in 10 waves of nine planes. It thoroughly sickened him. Stan Patterson said the bombs started to fall as the sirens sounded. The Air Force boys did all they could and the ack acks put up a good show.

On 13 March the Sydney Morning Herald reported various stories from survivors, including a Mr W Doyle, who said Darwin had been “caught napping” and the raid was “a repetition of the Pearl Harbour [sic] incident on a smaller scale.” On the 16th the same paper reported on Mr Justice Lowe’s appointment to review the whole matter in approving terms, and said stories about the raids had given “much anxiety”. Meanwhile newspapers across the country were full of the repeated raids on the Northern Territory, and further afield: Broome for example, having over 80 people killed in the attack there in early March.

An investigation was quickly commissioned by the federal government. The release of the Lowe Report occurred on 31 March, and it advised that deaths “did not exceed 240.” The government came in for some castigation over this, as early reports had put “deaths in the town” at 15, which as the critic in the Morning Bulletin in Rockhampton pointed out, had been taken to mean 15 in total. There was also some criticism for the length of time taken over the analysis.

This is hardly a “government cover up.” The essential facts of the first raid had been given. A deeper analysis of the attack would have taken much more work than Lowe and his assistance could give it in the time constraint. Lowe reported incompetence; there is in almost any military operation, just as there is in private enterprise or civil servants’ everyday work; we are all human. But in fact any analysis of all of the newspaper reporting of the time shows no secrecy: enemy attacks, government disasters, and their opposites in bravery and success were all given remarkably even coverage. In fact, the newspapers overall gave the government of the day a good metaphorical thrashing over the initial reports of “15 dead”.

Darwin continued to be publicised, and interest did not lessen or appear to be constricted: the Western Mail in Perth showed a photograph of a direct hit on the Post Office on 21 May; the raids were reported in many pieces of cinema news, while steadily the tide of war arose around the February attacks. If anything ironically can be said to “cover up’ the first Darwin raids it was the subsequent Darwin raids: they were all given reasonably accurate reporting, and hence public attention moved on from 19 February 1942.

Interestingly enough, there had been a “government cover-up” and a most successful one at that, although the secrecy can be laid at the door of the Royal Australian Navy rather than its federal masters. The raid by the four Japanese submarines in anti-shipping torpedo and mine attacks around a month before the 19th February strikes had been suppressed. These attacks failed: not one of the more than 100 mines laid by the submarines succeeded in sinking an Allied ship. Further, the submarine I-124 paid the price for attacking a warship rather than an unarmed merchantman: she was sunk by the corvette HMAS Deloraine in a short, sharp battle on 20 January 1942.

It was hardly an inconsiderable attack: four big submarines against the small ships of the “Darwin Navy” as it was sometimes humorously named. But testimony to the “Most Secret” security rating – the highest – the operation received, the action was kept quiet. It was for sound operational reasons too: the Navy and the American Allies, whose divers and ships were to the foremost in the operation, were trying to get inside the giant boat and recover its codebooks, which would give invaluable insight into current operations so long as the enemy did not know of their capture. The divers reached the submarine, but could not gain entry, and while more capable ships were brought in the Japanese carriers were readying themselves. On 19 February it all became immaterial, and the waters outside Darwin harbour were no place to be in an anchored salvage ship. The I-124 was abandoned to the depths where she remains today.

To return to the raids, in one sense there was some censorship of the media, and it’s hardly surprising. On 10 January 1942, in a “Secret” “Advisory War Council Agendum No. 2/1942” the Prime Minister, John Curtin, deplored the “dramatized enemy reports” referring to a “supposed bombing of Darwin” and issued an instruction forbidding the publication of “sensational reports from enemy sources unless officially confirmed.” The Sunday Telegraph of Sydney was named, and the Truth of Brisbane. What is most interesting however is the date of the instruction, 10 January, 10 days before the submarine raiders arrived in Darwin waters, and a full month and a half before the aircraft carriers arrived to avenge their fallen comrades. It must have been a most difficult time to be in government and to successfully weave a path between being open and being secret where necessary.

So where did the widely-held myth that the first raid had been “covered up” come from? Ironically, it might have emanated from the book which revealed so much to the nation, Douglas Lockwood’s 1966 Australia’s Pearl Harbour. To give the work the credit it is due, it was the first major gathering together of the facts; it was told well – Lockwood was a journalist, and could tell a story; and he went to considerable effort to interview some important sources: men such as Mitsuo Fuchida, the air leader of the first raid.

What annoyed Lockwood was the refusal in April 1964 by the Australian federal government to release the transcripts of the Lowe report. The censored sections (of the short version that was publically released) concealed the names of many people who had given statements, and who in many cases were still serving. Lockwood wished to examine their confidential questions and answers made to the Commission, presumably – for he lists the failures of the authorities in several pages of his work – to apportion blame more specifically. He would probably have argued in a subsequent book that the combat aircraft could have been better organised; alarms in general – perhaps including his invention of Melville Islander John Gribble’s supposed “warning” – could have received more attention; and so on. And so in his “Author’s Note” introduction, Lockwood argued that “comparatively little is known of what happened.”

But the attacks’ full outline: casualty numbers; infrastructure destroyed; ships sunk, etc., were indeed publicised. The stories of many survivors were given full rein in the press of the day. Lowe’s abridged report, with all the key facts, was made public. Indeed, Lockwood suggests that [because] “few Australians know that part of their country was so heavily attacked [was] that much was happening elsewhere at the time.” He cites Singapore’s fall; Rommel in the Western Desert, the Russian front and the Battle of the Atlantic” as being reasons for this.

Where Lockwood is wrong is not that Australians were not told, but that Darwin became submerged in the detail. A glance at the front pages of any newspaper around the world at the time shows the biggest war in history in full force, changing from the “Phoney War” days of 1940 to full-scale bitter fighting involving millions of people locked in titanic struggles.

The war was to continue at the same level of intensity for more than three further years. And then the whole European titanic struggle ended in a bunker in Germany, and some months later in the Pacific in two atomic weapon explosions. Post-war is there any surprise that hundreds of thousands of war-weary personnel in Australia, and millions world-wide, should want to become civilians once more, and forget the details of the greatest conflict the world had ever known?

There is though a second reason why Australians had a further barrier to learning about what went on in Darwin. It was simply that those progressing through the school systems were never educated about it. Australia, as is the case now, had a myriad of education departments administered by the states and territories, with varying curricula designed by those local authorities. The curriculum materials from the war onwards are in the main silent about the war in northern Australia.

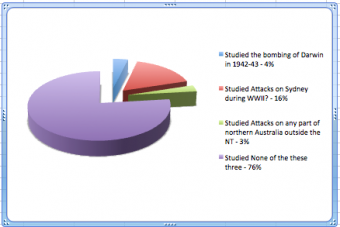

The results of a small survey is indicative. The school students of Australia were not taught about the matter: 96% of those surveyed had never experienced it as part of their school studies.

The first question asked of their school time:

1. Did you study:

a) The bombing of Darwin in 1942-43?

b) Attacks on Sydney during WWII?

c) Attacks on any part of northern Australia outside the NT (e.g.: WA and/or Qld)?

d) None of the above

301 answered d; 64 answered b; 15 answered a, and 12 answered c

The interesting aspect of the survey insofar as discovering WHY the Darwin raids are so-little known about is indicated here: 96% of the respondents – and therefore the country – had simply not been taught it in their school years.

Question Two asked:

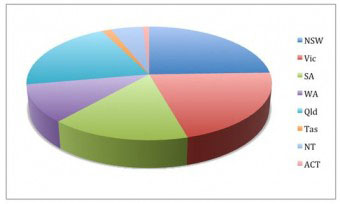

2. In what state or territory of Australia did you undertake primary and secondary school?

The results were: NSW: 96; Vic: 83; SA: 62; WA: 42; QLD: 80; Tas: 6; NT: 19; ACT: 4

Question Three asked:

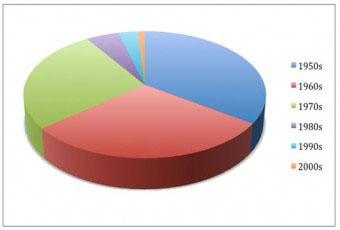

3. When did you attend primary and secondary school?

The results were: 1950s: 136; 1960s: 115; 1970s: 105; 1980s: 20; 1990s: 12; 2000s: 4

Not surprisingly, all of the NT residents had heard of the bombing of Darwin – but all of those who had studied it had done so in the 1990s and in the 21st century; reflecting the growing efforts of the Darwin City Council and the Northern Territory Government to highlight the raids. Those who had studied the attacks on Sydney by midget submarines all came from NSW, with two exceptions from Victoria, and one each from South Australia and Queensland.

Analysis of the decade people had studied in the curricula areas showed that almost universally people had never been educated about the Darwin raids. This included people who had attended high school in the 1950s, 60, 70’s, and to a lesser extent in the 1980s, and 1990s.

Indeed, the raids were not even commemorated very much in the place where they happened, let alone throughout wider Australia. For example, the Northern Territory News of 19 Feb 1972 covered the commemoration in a page five feature article – far removed from the nationally televised events of today. It was not until 1992, the 50th anniversary of the assault, that the event really gained prominence, and that was largely due to the efforts of the Darwin City Council, who supported financially and organizationally the events. The 70th anniversary saw around 10, 000 people attend the Darwin Cenotaph.

Australian school curriculums in the 1950s and beyond, in the oft-used title of “social studies”, was a combination of history, geography, and civics. In primary school and junior secondary – before students chose their own subjects for senior school – the history elements combined study of the First Fleet arriving in Australia in 1776; the colonization of the eastern seaboard of Australia; the country’s role in the British Empire, Western history such as Greco-Roman materials; medieval times; the Industrial Revolution, and the lead up to World War I, though not the war itself. World War II was covered, but in little detail, and nothing of the Top End being at war. For example, Emeritus Professor of History Alan Powell, of Charles Darwin University, comments about the 1970s:

I taught history at Scots College, Sydney, during that period, from a syllabus laid down by the NSW Education Department. There was nothing in it that related to the Northern Territory, let alone the bombing of Darwin – and, for that matter, scant reference to Australian History at all. Europe took first place.”

Historian Dr Peter Williams recalls:

I taught high school History and English in Tasmania and the Northern Territory in the 80s and 90s. Neither in the social studies, nor in the senior [grades 11 and 12] history curriculum, was any mention made of the 18 month Japanese bombing campaign against Darwin. I remember being mildly surprised, looking over the social studies curriculum on my arrival in Darwin in 1988, to see that students in a city which had been heavily bombed were not intended to learn anything of it – at least if the official curriculum was followed – which it often was not.”

Of course, a student could indeed miss out on an area in which the Darwin raids might be mentioned, fleetingly or extensively, through absence or simply inattention.

In summary, there has indeed been an absence of the story of the Darwin raids being imparted to school students – and this explains the general perception of “we weren’t told” amongst those hearing about the Darwin raid for the first time. There was no government cover-up – but there was a lack of national education.

Carrier Attack is published by Avonmore Books.

List of Works Consulted

(This article has drawn upon over 300 references in the book Carrier Attack, authored by Dr Tom Lewis and Peter Ingman, a study of the 19th February 1942 raids. Only those critical to this article are cited here.)

About Australia. http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/japanese-bombing-of-darwin Accessed May 2013.

A Secondary School Education Resource on the Bombing of Darwin,

http://www.darwin.nt.gov.au/sites/default/files/Bombing-Darwin-FEDFrontline.pdf Accessed October 2012.

Darwin Defenders 1942-45 Inc. http://au.answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20120424063442AAdn1UUAccessed May 2012.

Lewis, Tom, and Peter Ingman. Zero Hour in Broome. Adelaide: Avonmore Books, 2010.

Lewis, Tom. Darwin’s Submarine I-124. Adelaide: Avonmore Books, 2011.

Lewis, Tom, and Peter Ingman. Carrier Attack. Adelaide: Avonmore Books, 2013.

Lockwood, Douglas. Australia’s Pearl Harbour. Melbourne: Cassell, 1966. (pp. 192-200)

National Archives of Australia File: 816, 37/301/293, Reference Copy of AWM Confidential No.137. “Findings and Further and Final Report – Commission of Inquiry on the Air-Raid on Darwin 19th Feb. 1942.” Original. Mr. Justice Lowe. 1942 – 1942. 12082127. (Cited as the Lowe Report)

National Archives of Australia File: A431 1949/687. Bombing of Darwin – Report by Mr. Justice Lowe 1942 – 1949 66354, (Lowe Commission Report, Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia.1945. (Cited as the Lowe transcripts)

National Archives of Australia. A5954, 327/12. “Advisory War Council Agendum No. 2/1942.”

Northern Territory Library http://www.ntlexhibit.nt.gov.au/exhibits/show/bod Accessed December 2013.

Powell, Emeritus Professor of History Alan, Charles Darwin University. Email to the author, 6 November 2012.

SKWirk.com.au. http://www.skwirk.com.au/p-c_s-14_u-91_t-200_c-668/the-bombing-of-darwin/nsw/the-bombing-of-darwin/australia-and-world-war-ii/the-australian-home-front Accessed May 2012.

The Australian. http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/features/darwins-finger-of-shame-points-at-military/story-e6frg6z6-1226268053891 “Darwin’s finger of shame points at military.” 11 February 2012. Accessed May 2012.

“The Bombing of Darwin – Australia’s First Taste of War.” http://scheong.wordpress.com/2013/04/19/the-bombing-of-darwin-australias-first-taste-of-war/ Accessed May 2013.

Trove Digitized Newspapers. http://trove.nla.gov.au (Various cited in the footnotes)

Williams, Dr Peter, Historian. Email to the author, 6 November 2012.

Yahoo 7 Answers. http://au.answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20120424063442AAdn1UU Accessed June 2012.

Contact Tom Lewis about this article.